David Barrett started coding when he was six years old and hasn’t stopped since. So in a way, he really has been working his whole life to found and lead Expensify, the default service for many companies to process expenses. To give you some context on its growth trajectory, the company is the world's fastest scaling software of its kind. It grew over 130% in 2014, nearly 60% more than its closest competitor. The expense management startup outpaced overall market growth 28 times over, and it now assists over 16,000 companies.

Barrett’s success has stemmed from boldly embracing the unconventional. Before Expensify, He was the head engineer at Red Swoosh, where every year, he’d relocate the startup to an emerging market for a month-long retreat. Akamai acquired Red Swoosh, and soon after fired Barrett after he spoke out against its client, Warner Music, about the global record company’s sponsored music tax. Barrett is as vocal as his opera-singing spouse and nearly always takes the untrodden path. His approach to user acquisition is no different. And it’s paid off: Expensify has doubled its customer count over the second half of 2014 alone.

In this exclusive interview, Barrett dispels five myths about user acquisition and shares atypical truths about how to attract and retain new customers. Here, he offers a different — even counterintuitive — approach to how startups can achieve a lower customer acquisition cost (CAC), use their data, craft new user orientation flows, diversify the source of new ideas and quantify marketing spend.

MYTH: Your path to better user acquisition hinges on honing how you find, buy or attract leads.

REALITY: Success is actually about achieving a lower cost of acquisition through the integration of marketing, sales and product development into a single function.

Expensify is built on the belief that customer acquisition efficiency is its most strategic differentiation. “The days of perpetual loss in the name of customer acquisition — buying the same leads from the same places at the same price as your competition — are quickly coming to a close,” says Barrett. “The market ‘corrections’ that we’ve seen for most enterprise SaaS companies uniquely punish those with unprofitable models because while the potential for massive recurring revenue is unchanged, the strategy of massive negative-ROI spend to get it is coming into question.”

To fully understand Barrett’s reasoning requires taking a closer look at how he sees the evolution of the customer acquisition model over the last two decades. (It’s not lost on him how strikingly they resemble South Park’s Underpants Gnome business model.)

At first, the goal was to attract eyeballs. “That was the late 90s,” says Barrett. “It didn’t matter why they were visiting your site, or what they did when they got there.” The model was:

It didn’t take long until marketers knew that wasn’t enough. “Now we look back and laugh at how silly that was,” Barrett says. “Obviously eyeballs don’t make profit. Only profit makes profit.” In the late 00’s, the model shifted to:

In essence, eyeballs have been swapped for revenue. “So, just as we saw companies in the late 90’s with massive traffic logs but no profit, we’re seeing late 00’s companies today with massive revenue bases, but no profit — and no apparent path to ever get it,” says Barrett. “Even if companies argue that they could ‘cut spend and go profitable whenever they want,’ to me that sounds like an addict saying they can go clean, right after the next needle.”

To contrast these two prevalent customer acquisition philosophies, Barrett suggests a third (the streamlined strategy that Expensify has taken):

For Barrett, contemporary customer acquisition should focus less on attracting the external (eyeballs, revenue, etc.) and more on integrating internal functions, namely marketing, sales and product development, into a single purview. This is squarely in control of the company and will help significantly lower the cost of customer acquisition. “Most enterprise startups build a product for companies that is used by individuals, whereas Expensify builds a product for individuals that happens to work amazingly well in groups,” says Barrett. “This means we have consumer acquisition costs for enterprise deal sizes. This strategy is straight-up incompatible with a classic top-down sales organization and can only be pursued by a highly integrated marketing/sales/engineering organization.”

“What people fail to understand is that these functions are not separate organizations. In a well-run, fast-moving company, everybody considers all of these aspects in every decision they make,” says Barrett. “I admit it’s not a fancy plan, and certainly not a common one,” says Barrett. “But it’s becoming much more fashionable as the 2010’s go on.”

WHAT TO DO: Don’t assume your engineers can’t get a knack for marketing or that your sales team is unable to be conversant in product management. “None of this stuff is rocket science and nobody needs to be an expert in everything,” says Barrett. “Bring aboard passionate, creative people, build an environment that encourages crazy ideas, and get out of the way as much as you can. Sure, the results can get a little weird, but weird is great. Weird is your edge. If you’re not a little weird, you’re done.”

You don’t need to stack your management team with VPs of Last Decade’s Strategy. Onboard eager, versatile hires and get out of the way.

MYTH: Focus on extracting and extrapolating all the data you can to guide and measure user acquisition strategies.

REALITY: Don't wait for the data, nor pretend what little data you have is more significant than it is. Experiment and act decisively on data that excites you.

When it comes to how companies can responsibly and systematically test new user acquisition strategies, Barrett takes a different tack with data at Expensify. “Honestly, we just don’t, and you probably shouldn’t either,” he says. “At the end of the day, data is never there when you need it most. At best, data can help you make very small, incremental decisions. But if you’re a startup, you’re focused on big, broad swings — and data has no place in that.”

The dilemma with data at most early-stage startups is that your data is unlikely to be statistically relevant. “You don’t have enough users to draw any meaningful conclusions, and even if you did those users aren’t necessarily representative of your long term target audience. You’ve got data, sure. But not enough to make a genuine, data-driven decision, and pretending otherwise is a recipe for disaster.”

For Barrett, startups’ obsession with data is protective in nature not proactive in purpose. “Most people love data because it’s the ultimate CYA tool: nobody ever got fired for waiting for more data before acting,” says Barrett. “But by the time you have enough data to fully support your decision, it’s too late: you’ve already moved too slow, and someone else with more courage has already taken the opportunity, and now it’s over.”

In practice, the best marketing opportunities arise suddenly, unexpectedly, and without any chance of do-over. Demote data and get gutsy.

Take Expensify’s Concur integration as an example. “We were only going to launch it once. Concur was only going to get acquired once,” says Barrett. “There was just no way to get data on whether capitalizing it with a crazy integration was the best use of our weekend, and no time to get it even if it were. Once done, there is no A/B testing multiple messages. We had one shot to take advantage of the opportunity and deal with the consequences. The alternative was we pass and always wonder.”

Once done, whatever happens, happens. “It was either going to perform — and boy, did it ever! — or not, but either way, there was no sense spending a ton of time quantifying results to the Nth degree because there is no exact repeat scenario and thus no practical application for that data,” says Barrett.

WHAT TO DO: Don't wait for the data. Don't pretend what little data you have is more significant than it is. And don't waste time analyzing it just to make a pretty chart. The audience will forget it the second you go to the next slide, but the time spent making it is lost forever. “Just keep an open mind, consider all opportunities, act decisively on those that excite you, and move on,” says Barrett.

Every decision doesn’t need to be amazing. You just have to make slightly better decisions, slightly faster than your competition. The rest will sort itself out.

MYTH: When it comes to new user orientation flows, only use concise, powerful language with a prominent call to action.

REALITY: Clear, direct language helps, but isn’t a silver bullet. Authenticity and relevance are three-dimensional variables, so timing and response workflows are most critical.

When it comes to onboarding or orienting new users, everybody will tell you a long list of best practices for marketing communication: Deliver good design. Use concise, powerful language. Make a prominent call to action, ideally in the form of a single obvious link to click. Position a survey on the other end to normalize the results to make the data cleaner and more valuable.

Expensify engineered its welcome orientation flow differently. “I’d go so far as to say the best thing we ever did in terms of a new user welcome experience came about by accident,” says Barrett. “As background, we’ve always ‘rolled our own’ email marketing tools. The off-the-shelf tools are flashy, and seem like a great way for any non-engineer to start. But as an engineer, I couldn’t help but feel they were expensive, constraining and only seemed to streamline the easy parts of a campaign, while making the hard parts impossible.”

So Expensify created its own internal tool called Harpoon. “It’s a rich system that allows the company to do deep, real-time inspection of individual users and implicit groupings inferred by user activity — the sort of thing no off-the-shelf system could even imagine,” say Barrett. “But at the start, it was as rudimentary as it gets: every hour, it would just email everybody who signed up in the past hour. It could only send plain text, and only send from my personal email.”

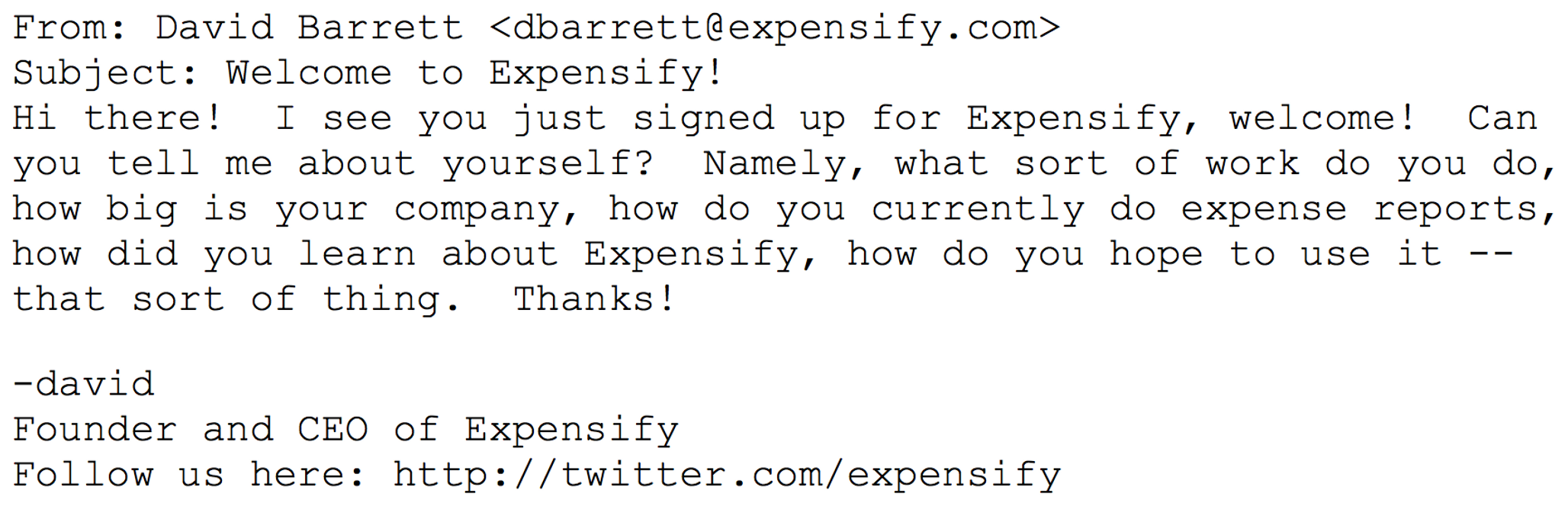

So, there was no impressive design with inspired language sent to new customers. Instead, the email that new Expensify users received looked like:

Barrett’s outreach and copy basically goes against all recommended best practices. It employs a single, rambly run-on sentence with a really ambiguous call to action and no link to click. “But contrary to all reason, it was incredibly successful,” says Barrett. “Whereas a ‘good’ pullback email will generate a 1-5% response rate, this template elicits a response 12% of the time.”

Here’s why Barrett believes it works:

- Timing. The email arrives immediately after a user finishes her first session and in a way that could plausibly be a true email straight from the CEO to the new user. “Because it sends every hour, to everyone who signed up in the past hour, it means it arrives on average 30 minutes after a user signs up — just long enough to give the product a shot, but not long enough to forget it,” says Barrett. “This means it comes right when the user has thoughts that she’d really love to share, but not so much that she’ll actually look up an address to send it to. But if the founder of the company writes her directly from his personal address exactly when she wants to talk most… Boom, we’re in business.”

- Suspended disbelief. Granted, it’s unlikely the founder would truly email a user at exactly that moment. But in this case, there is enough evidence of it being real to make it just plausible enough that people could consider it was possible. Barrett explains the new user’s potential thought process: “Okay. It wasn’t exactly 30 minutes after signup, but it also wasn’t precisely on the hour. It’s random enough that it could be from a real person. And it’s from an actual email address, written in the casual language of a real human. It’s not asking me to fill out a dehumanizing survey or click an obvious marketing link. It’s an earnest request for help.”

- Reaffirming response. Not everything is about the first message thrown across the chasm, but how and when your response is tossed back. “Most of the new user replies start with something like, ‘So this was probably sent automatically, and likely going to be read by some marketing intern, but just in case…’” says Barrett. “But when the company actually responds in a timely manner and it’s really the founder and CEO of the company reading their email and thanking them for their time, you’ve not just got a customer for life, but an evangelist.”

WHAT TO DO: Try out a similar, no-frills template and pay attention to the process built around it. Expensify reaps incredibly helpful input by doing so. “The responses weren’t some terse blurb providing a single datapoint to whatever question I thought to ask. They provided pages and pages of answers to the many, vastly more important questions I didn’t even know how to ask,” says Barrett. “It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that this single email was the difference between success and failure for Expensify. Don’t get me wrong: there are lots of things that need to go right, and this is just one of them. But had I not done this, I don’t think I would have learned nearly enough fast enough to do something about it.”

The early days of a startup are very, very hard. The only thing more valuable than the tangible advice you receive is the simple reminder that there are real users out there that are truly excited about what you do. Some days, were it not for that, I simply would've given up.

MYTH: The role of creativity in user acquisition and retention is in the hands of marketing and sales, those who are closest to the end user and data.

REALITY: Creativity in user acquisition is the composite of many new, little ideas. That comes from everywhere throughout the organization.

The role of creativity in user acquisition and retention does not just live with sales and marketing, but from across functions throughout the organization. Barrett cites a previously undiscovered essay by Isaac Asimov: “How do people get new ideas? In essence: an environment that generates new ideas is one where small groups of people are encouraged to explore the potentially absurd without fear of shame or embarrassment,” he says. “This environment naturally attracts some, even while it repels most.”

Barrett also takes issue with the use of the word “creativity.” “Like Asimov, let’s refer instead to ‘new ideas’ as opposed to the vague, all-purpose ‘creativity,’ which I feel is too often feigned through shock and ostentation,” says Barrett. “It’s silly to me that there are ‘creatives’ in a company, because new ideas are everybody’s responsibility. A great environment should consciously extract the top ideas from everybody, without regard to source. If anything, it should be biased toward ideas from the more unusual of sources.”

There’s a reason why a habitat for the broad cultivation of new ideas is so hard to foster. “Everybody else uses a classic enterprise sales organization, where salespeople are financially motivated to over-promise — even at risk of under-delivering,” says Barrett. “This means there is always a product management group trying to figure out what actually has been promised, and then an engineering team scrambling to make good on those promises.”

The reason everyone sticks to the traditional sales paradigm: it’s simple. “Everybody has one job, and you need a minimum amount of context to do that job. This means it's easier to hire people, easier to train them, easier to evaluate their performance, and less disruptive to fire them if they aren't performing. Everything is neatly bucketed and centrally managed.”

It’s critical to recognize how that organizational simplicity comes at a cost. “You can't help but build sh*tty products that way. This is because literally everybody in the company is focused on building a product to be sold to a decisionmaker who, in all likelihood, will never actually use the product themselves, and thus truly doesn't care how well it works,” says Barrett.

WHAT TO DO: Find ways to cull new ideas from different and all corners of organization, especially where the borders of functions overlap. Aim to focus your entire company on building a product to be used by end users. For Expensify, that shift in thinking has literally realigned every aspect of the company, from its sales comp strategy to its product management structure (they don't have one) to its project management (there are no deadlines) to its marketing (its branding is oriented to the employee, not the C-suite).

A startup is one giant new idea. By definition, the "experts" think the fundamental principle of the startup is absurd. If they didn’t, they’d have done it already.

MYTH: Marketing can be quantified and attributed to user acquisition efforts.

REALITY: Don’t believe the hype. These efforts work, but no one can say for certain which lever had the impact — and to what extent.

In trying to more effectively attract and retain new users, sales and marketing efforts can definitely misstep. Beware the tone-deaf emails or aggressively frequent outreach efforts. According to Barrett, the biggest mistake that Expensify made was believing marketing can be quantified despite all evidence that clearly stated the opposite.

“When we raised our seed round, our pitch was very basic: we’re going to raise money, spend it on ads, optimize until the CAC was less than the LTV, rinse, repeat, profit,” Barrett says. “Everybody acts as if this is how it works — nobody challenged our assumptions on this front. Even today, it seems like everybody does it this way.”

But the dirty secret is it doesn’t work like this for any company. Startups, incumbents, you name it. “Nobody has the formula nailed down. Scratch the surface of any successful company with a question like ‘What fraction of your revenue can be directly attributed to your paid acquisition campaigns?’ and you’ll generally get answers ranging from 25% to 0%, which is commonly phrased as ‘I have no idea.’” says Barrett. “Sure, there are exceptions. A small parade of CAC defenders will trot out. But that list’s very short, and none were remotely like Expensify.”

What Barrett is getting at is the difference between effectiveness of and correlations with paid acquisition. “To be clear, that’s not to say paid acquisition doesn’t work. It can and does — though rarely as well as it’s assumed to,” say Barrett. “In reality, it’s rarely attributable: very few businesses truly know their CAC, and so nearly no one knows the actual ROI of their marketing spend, despite almost everybody claiming otherwise. Especially when investors are around.”

Expensify could have avoided a lot of unnecessary costs: from financial expense to team morale. “I know better now,” Barrett says. “At the time, we blindly tried all the stuff everybody says is supposed to work: AdWords, billboards, social, content and more. And we were pretty stressed out about it. We assumed everybody had this dialed in, and we were just idiots. I had some very difficult conversations with our early marketing hires, basically holding them to what I now know is an impossibly objective standard.”

WHAT TO DO: Hold strong and refuse to over-invest in marketing spend that clearly isn’t working. Give yourself the time to make and learn from your mistakes. While this may sound totally obvious, don’t forget that the vast majority of startups spend themselves into oblivion making precisely this mistake, all the while being cheered on by everyone around them.

The Takeaway

When it comes to user acquisition, there are a lot of preconceptions masked as best practices. In reality, startups should challenge those standards and try on some of Barrett’s more original methods to gaining and retaining customers. Try to lower costs of acquisition by integrating marketing, sales and product development into a single function. Don’t let lack of data be your excuse; experiment and act decisively on data that excites you. User acquisition may be your purview, but creative solutions are deposited throughout the organization — mine for them. Lastly, avoid over-investing in or trying to quantify the impact of your marketing efforts.

“The enduring challenge is to maintain conviction in the face of skepticism from the smartest names in the industry. By today’s count, there have been many, notable VC deals for enterprise startups, which means every investor has an opinion on how to do user acquisition,” says Barrett. “We set out to build a ‘slow, organic, exponential-revenue-growth’ business in a world that is fielded by ‘fast, paid, linear-revenue-growth’ peers. Exponential always wins in the end, so long as there’s the fortitude and patience to see it through. That’s why our ‘slow,’ atypical model is massively outpacing that of our peers who were faster out of the gate.”