This article is by Dan Hockenmaier (founder of growth strategy firm Basis One and former director of growth marketing at Thumbtack) and Lenny Rachitsky (a former product lead and head of consumer supply growth at Airbnb).

As advisors to early and growth-stage companies, we spend a lot of time talking to founders about growth. One of the more common questions we hear, especially early on, is about finding more ways to grow. The questions are often phrased like, “How can we add some SEO?” or “How can we make our product more viral?”

Unfortunately, this often leads to founders running head-first into one of the most common startup failure modes: investing in too many channels at once, and as a result not investing in any one channel enough. As an example, betting big on both SEO and virality feels like a really good idea (“We’ll grow twice as fast!”), but in practice it rarely works. And it’s often not clear that either of these routes are even the right channels for your business to begin with. We find ourselves repeating this same advice over and over, and so in the hope of saving startups time and heartache, we decided to put our thoughts to paper.

In our experience, founders are often surprised to learn that there are very few routes to scalable new customer acquisition. For consumer companies, there are only three growth “lanes” that comprise the majority of new customer acquisition:

- 1. Performance marketing (e.g. Facebook and Google ads)

- 2. Virality (e.g. word-of-mouth, referrals, invites)

- 3. Content (e.g. SEO, YouTube)

There are two additional lanes (sales and partnerships) which we won't cover in this post because they are rarely effective in consumer businesses. And there are other tactics to boost customer acquisition (e.g PR, brand marketing), but the lanes outlined above are the only reliable paths for long-term and sustainable business growth.

To demonstrate this point, look back at the most successful consumer businesses of the last 10 years — every company achieved initial scale in a market by excelling at just one of three lanes:

The good news is that you generally only need to excel at one lane to build a successful business. The bad news is that it won’t be easy.

Once you get to even moderate scale, each of these lanes becomes highly competitive. In the case of paid marketing and SEO, you are competing for a customer’s attention. Paid marketing becomes a business model competition (who can turn this customer attention into enough value that they can bid more than anyone else for that attention), and SEO becomes a ranking algorithm competition (who can capitalize on their content in such a way that “deciders” like Google want to continue to send traffic their way).

In the case of virality, you are competing for something even more precious: a customer’s social standing. Consumers only want to recommend things that improve their relationships by genuinely helping other people with great recommendations, or perhaps just making them look cool. You can increase referrals with the right UX and incentives, but only to an extent.

Over time, companies typically layer on additional lanes (e.g. Thumbtack adding performance marketing on top of SEO) as they reach diminishing returns on their early growth channels, but in almost every case companies start with just one successful lane.

You may be wondering — why are there so few ways for companies to grow? Well, it’s because there are only a few ways for people to find out about new products. Think about it — how do you find out about new products? You either hear about it from a friend (i.e. virality), you come across it while doing something unrelated (i.e. content or performance marketing), or you get contacted directly by the company (i.e. sales, partnerships). That’s it. These are effectively the only channels companies have to find new customers. And thus, there are very few “lanes” for sustained growth.

.jpg)

Below, we’ll share our framework for picking your lane, walk you through three case studies of companies that became world-class at a lane, and then tackle some frequently asked questions. To develop this playbook, we interviewed founders, embarked on primary research, and drew from our own experiences at Airbnb and Thumbtack.

An important note before we go further: While there are just three growth lanes for consumer businesses, this does not mean that there are just three “playbooks” to drive growth — or that there will never be other options.

New lanes occasionally open up. And the lanes just determine the rules of the road — you can still drive down each lane in unique and creative ways.

As you’ll see in the case studies below, once a company starts executing with high sophistication they’ll often find a unique mix of channels, tactics, UX, and messaging that is difficult to copy.

THE FRAMEWORK

.jpg)

Ok, so there are three lanes and you need to win one of these lanes. How do you pick, and win, a lane? Too often startups often pursue this choice in a haphazard way, ending up betting on the wrong lane, or trying to win too many at once. To help you through this process, we’ve developed a three-step framework:

- 1. Validate that a lane is right for you

- 2. Commit the necessary resources to give the lane a real shot

- 3. Scale the investment to become world-class

Below, we walk you through each of these steps and share three real examples of how world-class companies approached each step in their respective lanes (Thumbtack with content, Airbnb with virality, and Booking.com with performance marketing). Let’s dive in.

Jump to the end of the post to see the framework in full.

STEP 1: VALIDATE

The first step is to validate (as cheaply as possible) that a given lane is right for your business. There are two approaches to validating this, which when combined will help you build confidence that a lane is worth committing to.

Approach 1: Determine which lane is a natural fit for your business model

Each lane is naturally suited for different business models. And since each lane is so competitive at scale, you’ll need the built-in advantages that come with your business being a naturally good fit. Here are a few rules of thumb that we rely on:

Performance Marketing is a natural fit if:

- You generate revenue directly from new users (e.g. purchasing a product, subscribing to a service), which you can then use to fund more marketing

- Customers are not naturally going to be looking for your product, and thus you have to come to them (e.g. a new DTC brand)

Virality is a natural fit if:

- Your product is better when your friends or colleagues are using it (e.g. Snapchat)

- The product is innately fun to share (e.g. travel photos, homes for sale)

Content is a natural fit if:

- Your users naturally generate public content (e.g. reviews or answers to questions) when using your product, which you can use to attract new users

- You have a lot of unique data (e.g. restaurants in Seattle, plumbers in Phoenix), which you can turn into rich auto-generated pages

Casey Winters wrote the definitive post on this framework for the First Round Review which includes a handy guide:

One useful shortcut: Learn from analogous companies using a similar business model in a different market. If they’ve been highly successful using a particular lane, it may mean you can be as well. For example, Rich Barton founded three companies that all ultimately mastered the Content lane: Glassdoor, Expedia, and Zillow. While these companies compete in different industries, they share similarities in customer searching patterns and content generation, and he has been able to repeatedly capitalize on this approach.

Approach 2: Look at your data

In a perfect world you could validate a lane through a live test, but the time and effort involved in directly testing each lane is highly variable. Performance marketing could take as little as 2-4 weeks to test. Virality (such as launching a referral program) can often be tested in 1-2 months. SEO typically requires the most investment, and many companies see zero results for 3 or more months.

For this reason, you’ll see that validating paid marketing is most often done directly through testing, SEO often validated entirely through third-party data (e.g. Google Keyword Planner), and virality is somewhere in the middle. Here are our recommendations for the signal to look for to validate a lane through data:

Paid marketing: Your tests generate paying customers with a healthy payback period

Because it is relatively easy and cheap to launch paid marketing tests through channels such as Facebook or AdWords, simply getting tests off the ground should be the core of your validation strategy.

The most important metric to measure is payback period: the amount of time it takes you to earn back what you spent to acquire a customer. This is critical because it determines how quickly you can re-invest in more paid marketing. For most businesses, the payback period is only going to lengthen as you scale, so it needs to be pretty good from the start. Otherwise you need to have a clear line of sight to improving it, such as through conversion rate or monetization improvements.

For low frequency transactional businesses (e.g. buying car insurance), a common benchmark to target is payback on the first purchase. For high frequency transactional businesses or subscription businesses (ecommerce, media subscriptions), payback within 6-12 months would generally be considered healthy.

Virality: Over 50% of your new customer acquisition today is through word-of-mouth, customers are naturally telling their friends and family about your product, and you’ve run a handful of successful experiments that increase this behavior.

If your most satisfied customers aren’t already talking about your product or sharing it with their friends naturally, it’s going to be hard to make virality the cornerstone of your customer acquisition strategy.

Even if they are, you also want to understand if you have the ability to influence this behavior, such as through an experiment where you encourage customers to share.

Content: There is a high volume of keywords that are relevant to your product, and these keywords are not dominated by competitors that will be difficult to unseat.

Keyword research through a tool like Keyword Planner can help you understand search volume for queries that are relevant to your business. You’re looking for keywords that are directly relevant to your product. If you sell wedding dresses online, a keyword like “buy wedding dress online” is much more relevant than “cost of a wedding dress." The former has 1-10K searches per month, according to Keyword Planner.

Similarly, you can search for these keywords to see who is currently ranking for them, to understand how stiff the competition will be. The #1 result for “buy wedding dresses online” is brides.com. By going to the Ahrefs website authority tool, we can see they have a domain authority of 84. That is pretty strong, and tough to compete with.

Case study #1: How Thumbtack validated SEO

Thumbtack is a marketplace for local services professionals in home services, events, lessons, wellness, and many other categories. The team was lean and fundraising was difficult for multiple years early in the company’s life. So when they turned their attention to accelerating the demand side of the marketplace at scale for the first time, they knew they would have to focus.

Sander Daniels, one of Thumbtack’s co-founders, was deeply involved in these efforts. Here is how he described the strategy in the early days:

Resources were limited, so we took the approach that we needed to choose bets carefully, and when we did choose, to go all in with basically 100% of our resources. We viewed everything else as a distraction.

But where was the right area to focus? The team brainstormed through hundreds of ideas to drive growth: email, blogs, guerilla marketing, partnerships, paid marketing, and so on.

Then one day, another Thumbtack founder was at a bar in the Castro, and struck up a conversation with a stranger. When the conversation turned to Thumbtack, the stranger opened up his phone, did some searches, and said, “You know… you have an enormous SEO opportunity.” This kicked off a chain reaction that ultimately helped Thumbtack reach breakout scale. And that stranger ultimately became an angel investor, mentor, and first outside board member — but that’s a different story.

Sander describes how the team validated that SEO was the right approach:

“It wasn’t just a random bet, it was a calculated one. We validated it in three primary ways, and these three things combined gave us confidence that if we executed well, the channel would pay off:

- Keyword research. “We looked at the Google Keyword tool and saw that there were people out there searching in volume for keywords that matched what our product offered. People are out there searching for “movers in Austin” and “electricians in Tallahassee”. And for example, they’re not searching for “app to communicate with my friends where my messages disappear after they’re viewed”. So for Snapchat, SEO makes no sense.”

- Competitive research. “We looked at the competition and saw that it wasn’t a supersaturated space. The players in SEO were a lot of local players, not national players, so we thought we could make an impact.”

- Analogous companies. “We had seen other companies in adjacent spaces like Yelp and TripAdvisor find success in SEO.”

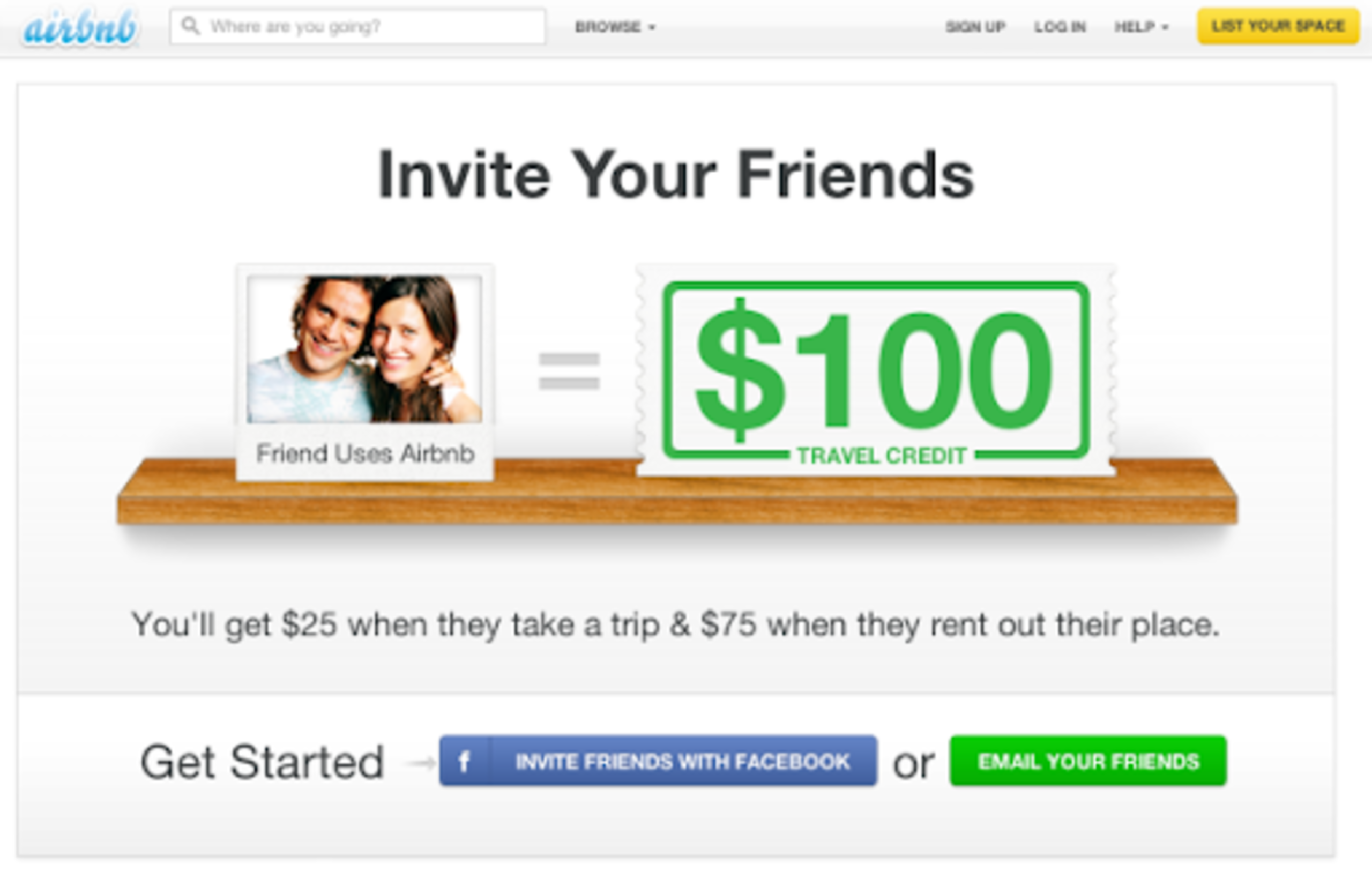

Case study #2: How Airbnb validated virality

The majority of Airbnb’s early growth was driven by word-of-mouth: Travelers telling their friends about the great time they had staying at Airbnbs, and hosts telling their friends about the income they’re making hosting on Airbnb.

As the company matured, accelerating growth became a topic of conversation. There was already a small team working on performance marketing (accounting for about 10% of bookings), and a nascent SEO team, but the vast majority of growth continued to come from word-of-mouth (over 50% of bookings). At this point, Airbnb had three choices: double-down on what’s already working (word of mouth), invest further in one of these potentially untapped opportunities (paid or SEO), or try something completely new. The team decided to double-down — to invest in accelerating word-of-mouth further. And this investment led to the one of the biggest accelerations of growth in Airbnb history.

How did the team make this decision? First, they looked at the natural behavior of what was already happening — strong word of mouth. They had a hypothesis that amplifying an existing behavior would be a lot more effective than trying to create a new one, and noticed that a lot of users took screenshots of Airbnb listings to send to friends — a behavior that could be facilitated with product.

Second, there was data from a nascent referral program already in place built by co-founder Nate Blecharczyk, which was seeing some use, despite the lack of resources behind it. Here's how Gustaf Alströmer tells it:

"Airbnb actually launched a referrals program in 2011 but it was kind of forgotten.

Over time, the general consensus was that referrals didn’t really work and that it wasn’t worth spending time on. But luckily we were storing a bunch of data, and when we looked at it again, we noticed we were generating millions of dollars in revenue from this program. Plus, we had a great base of data that we could tell there was a lot of room to expand it.”

Case study #3: How Booking.com validated performance marketing

Unlike Airbnb, Booking.com’s early growth came from through SEO. But it quickly slowed down. Here’s how Arthur Kosten (CMO of Booking.com from 2003 to 2012) tells it:

“The founding company behind Booking.com (bookingsportal) actually started off as a meta-search business, and SEO was a growth driver early on. But eventually, growth started to level off because we were doing some gray-hat stuff and Google started to penalize us.

So we began exploring new ways to grow. At the time, Google was taking off like a rocket ship, and the users had so much purchase intent while searching. We thought, if we could get good at Google, we’d do really well. We thought – what if we try AdWords?’

And so with this natural extension of their SEO work, the team ran some early paid ad tests. Kosten continues:

“We happened to have a bunch of simple templated landing pages (e.g. “Hotels in Paris”) from our SEO experiments that were easy to test with paid ads. So we ran some tests. And these tests showed a lot of promise – payback was immediate with the first transaction. As we were almost completely bootstrapped and cash constrained, we didn't have the luxury of investing marketing budget for future growth.

People talk about product/market fit. We realized we needed product/channel fit. And it became clear Google AdWords was that for us.”

And so with this early validation, Booking.com took their landing page strategy to the extreme – which we’ll explore in Step 2.

STEP 2: COMMIT

Once you’ve validated a channel, the next step is to commit to the lane. In our experience, most companies underestimate how large and disciplined the effort will need to be to turn any of these lanes into a superhighway.

Committing to a lane generally includes doing two things, both of which can be scary, particularly early in a company’s life:

- Dedicating a significant amount of cross-functional resources to the effort, including product, design, marketing, and engineering

- Influencing the core product roadmap and customer experience to optimize for the lane being pursued

Let’s look at how each of our example companies committed to their respective lanes.

Case Study #1 (continued): How Thumbtack committed to SEO

The Thumbtack team had conviction that SEO was the right channel to bet on, but knew it was still risky. Sander Daniels describes what the team was facing:

“SEO was a big bet because it takes a long time to see results. Often you start investing in it, and the first results you see are 6 months in and they’re not very encouraging. You only start to see results that impact the business after 12, 18, 24 months.

So we chose deliberately to put the entirety of our engineering, product, design, marketing, and operations resources - which were maybe 12 people at the time - against success in this one channel. It was a company betting decision.”

The first wave of this investment was in the “mechanics” of SEO to lay the foundation. This meant investment in three primary areas:

1. Site architecture

The team built out thousands of pages targeted at high value keywords, and optimized their entire website and URL structure for SEO. This meant making it as understandable and crawlable by googlebot as possible. Importantly, in some areas this came at the expense of the user experience. These were hard tradeoffs to make, especially before SEO was yielding any benefits.

One example was the geographically-based “directory” structure Thumbtack built. The incumbents in the space at the time were companies like the Yellow Pages, which had essentially taken an old paper directory and put it online. Thumbtack didn’t think this was ultimately the right user experience. And yet, to optimize for SEO at the time, this directory structure was beneficial because it would allow Google to quickly understand their site architecture and rank the relevant pages.

For example, Thumbtack chose to include links to all 50 states on their homepage, as you can see in the image below. No consumer would ever use this — they only cared about their own city — but it was how googlebot wanted to crawl it.

2. On-page content

To support the new pages, the team needed a massive volume of high quality, unique content. They built a team dedicated to content, which curated user-generated content like reviews and the profile pages of service professionals, and adapted it for the needs of different kinds of pages. At first this was a highly manual effort. At its peak, there were hundreds of people across multiple offices entirely devoted to content curation and generation. However once the company had meaningful engineering resources, they began investing in automation of this process, an initiative that continues today.

3. Linkbuilding

In order to get all of these pages to rank, it was important to send a signal to Google that thumbtack.com was reputable. The primary way the team did this was to invest in earning links from many reputable, external sources — often called “backlinks.”

To provide a sense for the scale of this effort, one of the most successful initiatives became known as the “Small Business Friendliness Survey.” It involved surveying about 15,000 service professionals each year on how well their local state and city governments supported small businesses. They used this data to create many locally-targeted press releases. In fact in the early days, for each wave, Sander personally wrote 130 individual press releases. These press releases were pitched to a database of every local newspaper, radio station, TV station, chamber of commerce, state and national senator, governor, and mayor — some 30,000 contacts in all.

All of this work to create high-quality pages that brought in visitors was just one step of the puzzle. Once there was enough traffic, the team began experimenting with increasing conversion rate, ultimately launching hundreds of experiments which in total increased conversion rate by more than 2x. For example, one common area of testing was to add and reorder the questions that customers saw when describing their projects. Because they needed a tool to quickly launch and analyze these experiments, they also built an in-house system that was effectively an Optimizely, Mixpanel, and Mode in one.

So, what did all of these efforts yield? For the first 3 months, almost nothing. And then a trickle of traffic. At 6 months, there still wasn’t much traffic, but there was at least enough to start analyzing. At 18 months, it became a meaningful share of consumer traffic to the site. At 36 months, it was the primary form of customer acquisition. These lead times are not uncommon, and can cause companies to give up hope on SEO.

Case Study #2 (continued): How Airbnb committed to Virality

With a clear mandate to double-down on the referrals program, the Airbnb growth team set out to commit to their first big experiment. Here's how Jimmy Tang tells it:

“We recruited a product manager, a designer, and three engineers. It was a pretty kick-ass team. We actually started thinking about ourselves like a startup. We had so much passion for what we were doing, we wanted to have our own space where we could live and breath the referrals program. Fortunately we knew of a site where we could book a home to work out of :)

We found a place, booked it, and did a one week offsite where we worked together super closely. And that one week laid a super solid foundation for us to build on going forward.”

When the team got back from this offsite, they stayed together and continued to work on this full-time for about three months. Over time they pulled in help from other teams, picked up an additional full-time engineer, and after writing over 30,000 lines of code, launched across Web, iOS and Android.

The impact was clear immediately. Gustaf Alströmer again:

“When you look at the referrals program this year, vs. other sources, it was outperforming YoY growth of every other channel, growing at 900% YoY. Also, referred users were better than the average user – they converted at a higher rate, and also referred more users.

There is a compounding effect because these users know how Airbnb works, and so they are more successful. And we weren’t even halfway through on all of the iterations that we wanted to take with this program.”

With this early success, the team increased the size and scope of this team — which we’ll cover in the third part of our story.

Case Study #3 (continued): How Booking.com committed to Performance Marketing

With the success of their early AdWords experiments, the team at Booking.com committed to the landing page strategy. Arthur Kosten shares how:

“We found a company that had a massive list of points-of-interest around the world, about six million of them. We realized that if we could do this at scale, we could create six million pages to point Google ads to. But this was way before Google Maps, or the iPhone, and geo-coding was hard. For example, we didn’t know the GPS coordinates of hotels. So it was a huge project. We settled on a map interface that allowed individual hotels to select their location on a map, to give us their exact location. This allowed us to show users which listings were close to thetse POIs on our landing pages.”

With this MVP built and showing early success, Kosten says the team started to double-down on AdWords:

“We first started by constraining the marketplace. We created a bounding box for every location (e.g. “Hotels in Valencia”), and for each location created a landing page with a map of the area, all of the hotels in the area, the POIs, and search box. We constrained by language, translating the pages into many languages, with hundreds of translators on the payroll at one point. So in places where we might not be able to compete geographically, we could compete on Japanese, Korean, Russian, Arab, etc queries.

At this time Expedia was 100x bigger than us, but with this approach we could pretend we were a big company in each of these specific cities, because no one knew we didn't have any supply anywhere else. When people land on the landing page, they were like wow, so many hotels in this city!”

Unlike the other two lanes, the size of the team necessary to commit to the performance marketing channel can be small. Here's how Kosten says it worked:

“It was actually only two guys for a while – one banker (Peter), and one coder. I always believed that the secret to our success was that we were not heavily automated for most of our early spend. Peter (the banker) was extremely competitive. He would scream and shout when he was losing his #1 position. He had a simple success criteria: win the auction for all of the important words, and make money on it.

This small team continued to run the program even past $100m in spend. We started paid search in 2004, and in 2008 it was the biggest source of growth.”

In our third and final step, we’ll explore how each of these companies scaled their investments across performance marketing, virality, and SEO.

STEP 3: SCALE

Once you have committed to a lane and start to see meaningful results, the next phase is to become world-class at the lane. The hallmark of this third stage is overcoming diminishing returns. Virtually every customer acquisition channel becomes harder over time because you are acquiring lower and lower intent customers. This is often referred to as the S-curve of growth.

For paid marketing, this typically means that your customer acquisition cost will increase over time. For SEO, you’ll have to start targeting less relevant keywords and lower intent customers, which will result in lower conversions rates. And for virality, the percent of potential customers that haven't already heard of and want your product will reduce over time, so you’ll see a degradation in K-factor (or the number of additional customers each new customer refers) over time.

Scaling your customer acquisition channels requires outrunning the challenges of diminishing returns. Want to build a world-class company? You need to become better and better at competing in your lane.

Let’s take a look at how our case study companies overcame these challenges.

Case Study #1 (continued): How Thumbtack scaled SEO

Thumbtack faced many hurdles to scaling SEO. One key area they focused on was the relevance of customer intent. A key limiter in SEO is the number of people performing searches that are relevant to your product. Thumbtack’s initial success came in keywords that indicated a very high intent to hire a pro, but ultimately, they had to expand to lower intent searches because they had saturated the high intent ones. Instead of just targeting customers looking to “hire a landscape”, they expanded to those searching for the “cost of a landscaper” or “landscaping ideas”. To do this, in addition to launching new pages to target these keywords, the team had to develop entirely new approaches to the user experience and content to give customers what they were looking for.

As the team fought these scaling challenges, they grew the channel to millions of unique visitors per month. But regardless of their efforts to combat diminishing returns, the year-over-year growth rate from SEO began to slow. The team knew they needed to layer on additional approaches to growth.

Over the years, Thumbtack had increased the value of each new user that signed up by improving customer retention, which allowed them to significantly expand their paid marketing efforts. And even more importantly, they invested in creating a compelling customer experience, which grew repeat and direct traffic, which today represents the largest and fastest growing share of the business. Sander Daniels describes this arc:

“Success in SEO bought us the time to invest in what we ultimately saw as the most important part of the business, which was to build a delightful product and trustworthy brand that drove repeat use. It was about 4 years in that we reached enough scale that we knew SEO should no longer be the primary lens.

We started viewing everything through product and brand. And we were excited to reach that point. We didn’t start the company to become SEO experts, we started the company to create economic opportunity for pros and to create a trustworthy brand for customers.”

Thumbtack’s growth story:

Case Study #2 (continued): How Airbnb scaled virality

With the success of the first major experiment behind them (the relaunch of the referrals program), the Airbnb team scaled up their investment in increasing virality. In addition to continuing to optimize the referral program, they invested in:

- Making it easy to share your favorite listings with your friends (e.g. through SMS)

- Creating shared “Wishlists” to help you plan a trip with friends

- Encouraging you to invite your friends to your itinerary after booking

The biggest wins over the first couple of years of the guest referral program came from:

- Making it easier to find the referral program on both desktop and mobile

- Conversion funnel improvements on both the send and receive side

- Decreasing referrals cannibalization

Gustaf Alströmer shares more:

“The most important win was simply making the program more discoverable. We measured our own success by keeping a two key metrics 1) % of WAU that saw a referral entry point 2) % of WAU that engaged with the referral program.

As a result, in the US referrals grew from about 1% of first time booking/new users to 15% of first time bookings/new users. We used different ways to track what % of these bookings that were incremental and which would’ve happened without the referral incentive and got cannibalization rate down to ~30%. It’s nearly impossible to get cannibalization down to 0 and it’s not an easy thing to track but with some precision you can inform your financial model.”

At its peak over the next five years, the team grew to seven people, including four engineers, one designer, one data scientist, one product manager, and one financial analyst. Alströmer continues:

“The beauty of this team was that we could scale it’s impact 40x without increasing the size of the team.”

A few years in, the team split into two — one team focusing on guest virality and one team focusing on host virality — in order to delve even deeper into these opportunities. Just the host-side team later grew to seven full-time team members, and mostly focused on the referrals product, founding success in a number of areas:

- Personalizing referral bounties

- Smarter friend suggestions

- Making it even easier to find the referrals program

Though over time the incremental wins from this channel diminished (like any growth channel) the investment in virality, and specifically referrals, was a critical building block to Airbnb’s growth story.

Airbnb’s growth story:

Case Study #3 (continued): How Booking.com scaled performance marketing

With the SEM strategy showing a lot of success, the team at Booking.com did something few other companies do — they used their SEM conversion data to inform the company’s overall supply-growth strategy. Arthur Kosten explains:

“Our goal as an organization was to find out why we were losing in the paid ads auction – what the competitor was doing better, and how do we get the supply we needed to win. Our process was: Do we have demand? → Do we have inventory? -> Is it the right inventory? → Do we have availability? -> Do we have conversion?

If we had enough customers coming in on queries that were high intent, we would want to (eventually) be #1 on those keywords. The team never wanted to believe they were losing a keyword because our competitors are being irrational. You cannot be irrational for too long because it’ll put you out of business. So if someone else was winning, they were doing something else better – content, availability, conversion, landing pages, selection, ranking, translations, funnel. Nothing was sacred.

Our goal as an organization was to find out what could we do better to serve these users – Different supply? Cheaper supply? Different rank order? Better product content? Availability at other dates? Something else?”

To do this, the team set up processes that shared insights from the performance marketing team throughout the rest of the organization.

“Most of the discoveries we made about why we were losing originated through the team’s daily process. I’m losing money on this, why? Peter always started with a hypothesis, ran SQL queries, and figured out what was what is going on. These SQL queries then moved to an internal websites, which the team used to diagnose problems.”

Throughout all of this, the team stayed small and lean for a while but then scaled up. Kosten sketches out how that worked:

“For a very long time, probably from 2004 to 2010, Peter was leading all of this, doing almost half the spend personally.

Around 2006, new people joined the team and built new screens and dashboards which informed the supply team's efforts. Then another coder joined the team later. In 2012, the team was about 20 people, driving $1B in EBITA. This team started to include a lot of DS/mathematicians, campaign managers who helped with localization, mostly to help Peter spend his time more efficiently.”

Eventually, this team split into two teams:

1. Peter’s team focused on top to mid-tier markets2. A high-tech product tech team going after long-tail markets”

Looking back, a few lessons stand out to Kosten:

"We were competitive for so long, not because it was one big fantastic thing we did, but we kept improving each of these steps 5-10% at a time. Also we were extremely efficient – the supply team delivered supply that was actually being looked for. We also made sure that anything that was high value was supervised by humans. When there is a human there, he’ll scream and shout when something is wrong.

When paid marketing is just a function, optimizing campaigns in a cubicle, it doesn’t inform the rest of the business, and the funnel doesn’t work. There just isn’t much you can do to optimize your campaigns, it won’t work. Finally, think about product-channel fit. How can you create a product / company / organization that the machinery of the org was built to fulfill the needs of the customer.”

Booking.com’s growth story:

PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER:

Here is a visual representation of the framework that we’ve been building along the way which you can reference as you’re making decisions at each step.

But we all know it’s not as simple as following this framework. Operating a startup is a messy business: the future is uncertain and resources are scarce. To help you navigate, here are our answers to some of the most common questions we hear from companies that are trying to put it into practice:

Who should be leading these efforts and making key decisions?

During the “validate” stage, it’s common for a product manager or marketer to own the process. The decision to commit to a lane is a whole-company decision which ultimately has to be made by the CEO, so this owner’s key job is to tee up the right information to allow the executive team to make well-informed decisions.

During the “commit” stage, the effort will quickly become significantly more complex and begin involving multiple teams. However it is still useful to have one person who is ultimately accountable for the success of the initiative and holds all of the moving pieces in their head. This is often a senior marketing or product person.

During the “scale” stage, the original owner may be able to scale with the effort, or it may need to be owned by a more senior person.

I tested a lane and got pretty bad results. How do I know if that means a lane won’t work, or if my approach just wasn’t right?

This is one of the most difficult questions to answer when it comes to customer acquisition. And while there is no set formula, here are a couple of questions you can ask yourself to determine if you’re on the right path.

- Just how far off the mark are we? If you’re off by an order of magnitude (e.g. payback periods are much too long, or initial keyword research suggests there isn’t enough relevant search volume to make a dent in your business), it’s unlikely that you can simply execute your way to success. But if you’re off by perhaps 2-3x, you’re in shouting distance and may want to do more work to validate.

- Have we taken a “real” shot on goal? It’s important to understand whether your testing is a close enough approximation of what your ultimate program might look like. For example, does your ad copy, conversion flow, referral mechanics, and payment flow roughly resemble what you think it might once you commit? If not, it might be worth going back to understand how you can run a more robust test.

- Is this lane a natural fit for your business? Revisit the suggestions we shared above to help you gauge whether that lane is ever likely to work for you.

How does the timing of each step of the framework line up with fundraising?

No two stories are exactly the same, and you obviously have to do what is right for your business and fundraising needs. But here are some rules of thumb that we commonly observe:

- When raising a series A, it can be very effective to be able to share data from the “validate” stage and your plan for how you will commit to one or more lanes once you have raised.

- By series B-C, most businesses are well into the “scale” phase and seeing meaningful results in at least one lane. This demonstrates that you don’t only have product market fit, but that you have a repeatable customer acquisition engine and business model to support it.

- Around series C-D, many businesses are starting to see the impacts of diminishing returns from their core acquisition lane. This often means that they need to do one or both of (a) commit to and scale a new lane or (b) expand into meaningful new markets or segments where you can get additional leverage out of your existing customer acquisition lane.

Investors want to know that you know how to turn their money into more money. Demonstrating validation of a scalable customer acquisition lane is one of the most important components of making your case.

The biggest customer acquisition mistake we see companies make is underestimating the time and effort it takes to make a lane really work, and spreading their efforts too thin as a result.

It is easy to see why this happens. It’s scary to make the leap into a big investment when resources are limited and speed is of the essence. We hope this framework can help give you the structure needed to evaluate your options methodically and make big, disciplined bets in the right lanes.

And remember, all it takes is one highly successful lane to win the race.

Huge thank you to Sander Daniels, Arthur Kosten, Gustaf Alströmer, Dan Hill, Brain Balfour, and Casey Winters for their contributions to this post.

Cover photo Getty Images / Xuanyu Han.