Alex Rampell wrote and sold his first software when he was 11, but he knew nothing about what to charge customers. Checks just showed up at his house for licenses to his products, which he started selling for $5.

As luck would have it, at the same time he hit 1,000+ software license sales a week, he was also taking high school microeconomics, learning about the elasticity of demand. What he learned in the classroom by day, he immediately applied to his business at night, ultimately raising the price of his product to $18.95.

For many startups, it seems mission critical to pinpoint the perfect price as soon as possible. But according to Rampell, now CEO of alternative payment startup TrialPay, the real lesson is you can’t, and you shouldn’t.One price means you’re leaving a lot of money on the table. At First Round’s recent CEO Summit, he explained exactly why this is, and how to escape the pricing trap.

Optimize Revenue with Multiple Prices

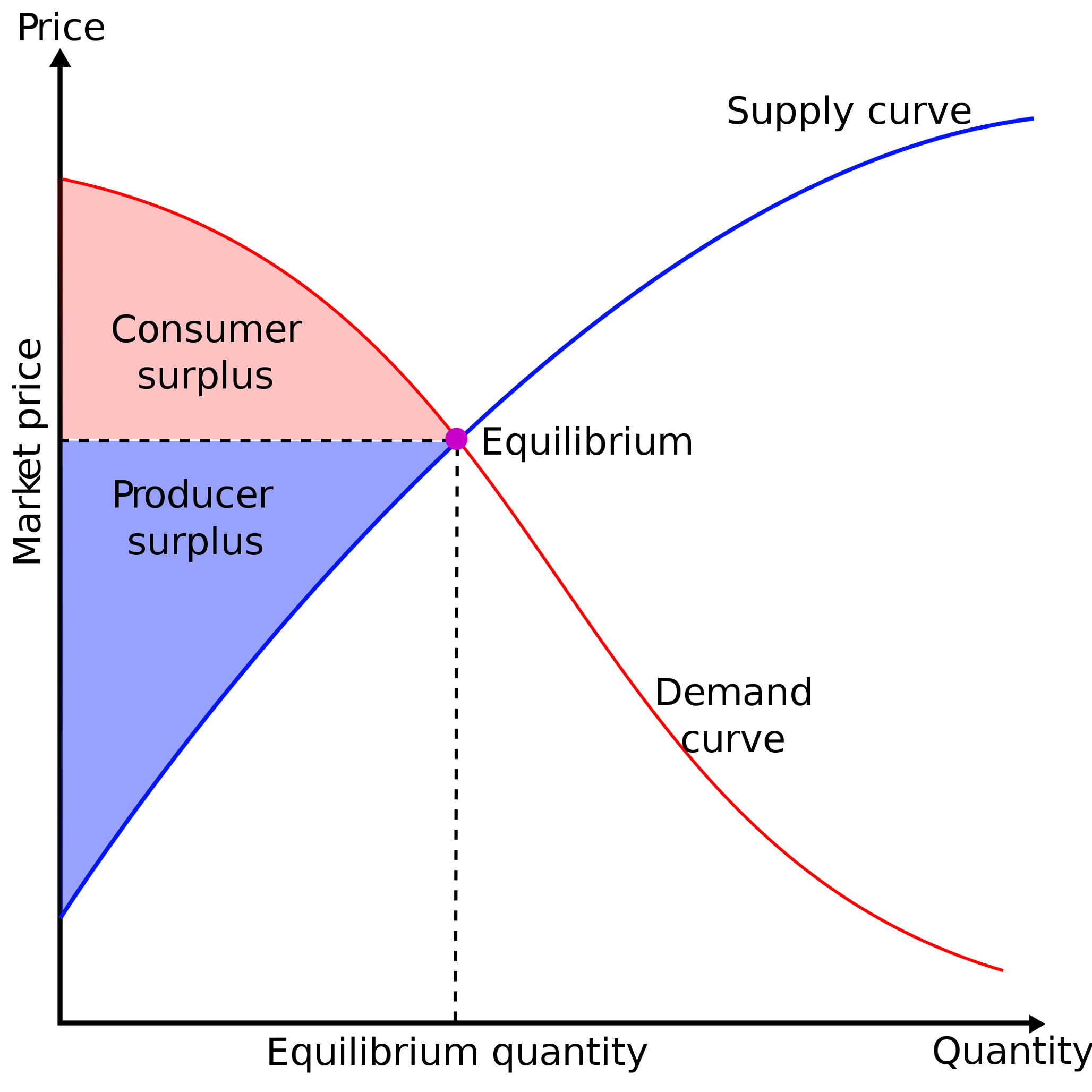

Anyone who has taken economics knows this graph. You have your downward-sloping demand curve and your ascending supply curve. When you’re pricing your product, the key region on this graph is called “consumer surplus.”

This graph tells you important things, like:

- Some people are willing to pay a lot more for your product than you’re currently charging.

- Some people won’t buy right now because the price is too high.

- The equilibrium price that will capture the most customers.

Product-market fit is the holy grail for all early-stage startups. But you get there faster (and ensure that your business model works) not just by finding the ideal price, Rampell says, but rather by segmenting your customers and selling different products to optimize your revenue across the board.

This doesn’t mean offering child or senior discounts. It requires segmenting customers based on one characteristic: their willingness to pay for various products.

Take the example of Nike running shoes. Consumers can pick between three very similar models: the premium Luna Eclipse at $135, the mid-range Air Max Tailwind at $110, and the entry-level Air Max Compete at $75.99. They’re pretty much the same shoe, but they each draw consumers who shop with different sensitivities and desires.

“I’ve owned a lot of different shoes,” says Rampell. “I’ve bought $250 shoes. I’ve bought $50 shoes. I once used somebody’s shoes that I found in the locker room. I ran about the same speed regardless.”

The key is that people self-select.

It’s not that they are making irrational purchases. After all, the Nike Eclipse may be a little bit better. The Compete might be a little lower in quality. But the difference in the material cost between the two is probably not $60. It’s probably a couple of dollars. It doesn’t matter. By allowing customers to group themselves where they feel most comfortable, Nike is extracting the most revenue possible.

Uber offers a similar take on the same concept. Some people are willing to shell out to ride around town in an SUV because they can afford to do so and want the luxury. More price-sensitive consumers are likely to choose UberX because they value saving that money more. But Uber and Nike are special cases.

How can startups segment their pricing when they don’t have a physical product? This is where things can get complicated, and where founders need to get flexible and strategic.

Pricing differences can be based on many different factors. Your company could pro-rate charges, for example, or offer certain features for one price, and others for another price (freemium models capitalize on this tactic), or you could offer upgraded support. It sounds straightforward enough, but combining these factors in a way that tiers pricing and still appeals to users can be tricky.

Embrace (Limited) Complexity

Counterintuitively, introducing complexity can actually help you find product/market fit faster.

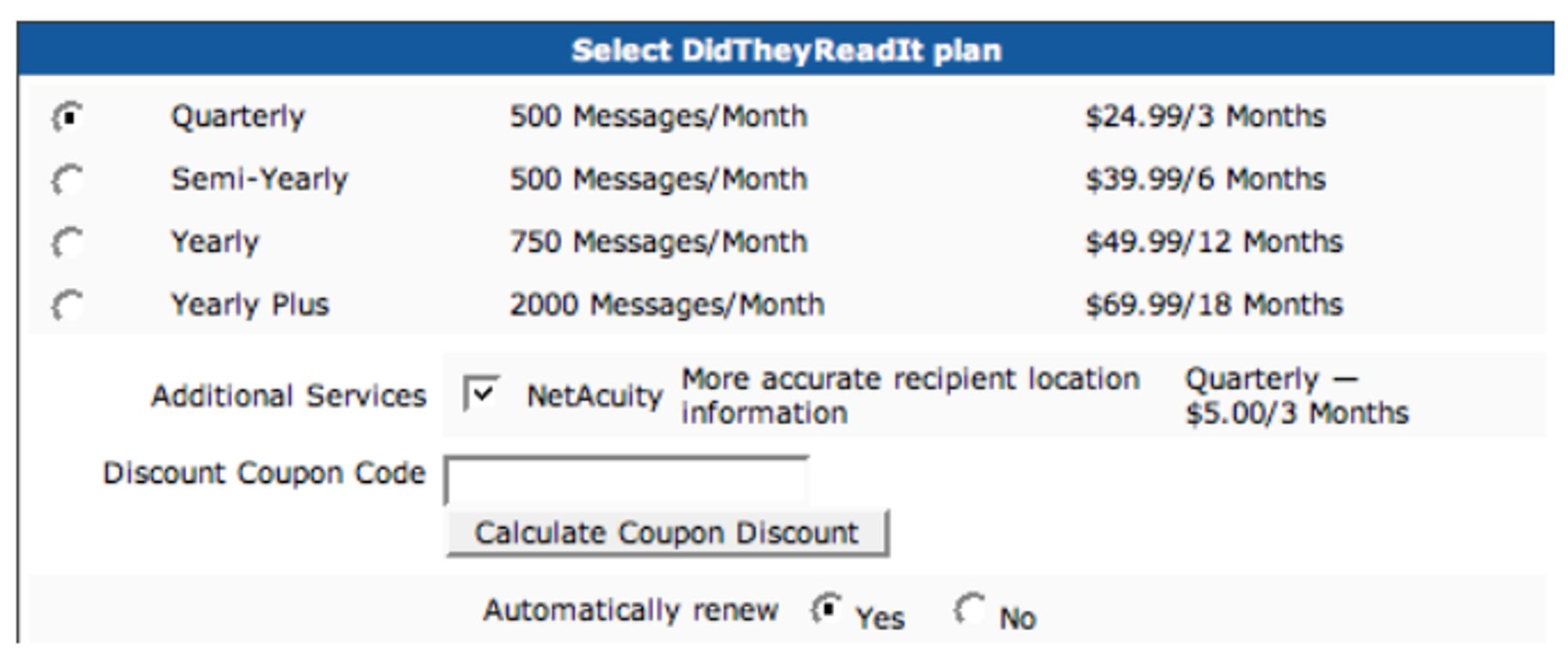

As an undergraduate student at Harvard, Rampell and business school student (now investor/entrepreneur) Chris Dixon launched an experimental product called “DidTheyReadIt.” For a fee, they would embed tracking pixels within emails their customers would send. When recipients opened the emails, the pixels would render and report back the exact time the message had been read.

Quickly, they started attracting business from both companies and individuals. Pricing the product took a lot of experimenting and they eventually decided to offer different lengths of subscriptions to maximize revenue.

Even though almost half of their customers opted for the annual subscription option, they made the most money on the smaller segment: Quarterly customers who had a higher lifetime value.

“That’s the interesting thing about pricing,” Rampell says. “You have to continually test for a structure that maximizes value beyond initial customer acquisition. Never set just one price.”

Segmented product offerings — like silver, gold or platinum membership — do a great job capturing consumer surplus. Total revenue doesn’t depend solely on one product’s price at time of purchase.

“It’s very valuable to test how you segment,” Rampell says. The results will often surprise you. For example, when he got rid of the monthly plan for his email tracking startup, most customers simply upgraded to the quarterly plan. He hardly lost anyone, even though he thought he would.

Use Transactions Wisely

Rampell founded TrialPay based on one idea: That checkout pages didn’t have to just be a point of exit. They could be used to retain customers and grow revenue by adding additional options.

Consider movie theaters as a prime example. Ticket sales don’t come close to covering what theaters pay for real estate and film licenses. Selling popcorn, soda and snacks at 10x their cost is how the cinema economy really works. This strategy of cross-selling is crucial for movie theaters (there would be no profitable product-market fit without it!). But this also works for many other businesses that might not view themselves in this light, Rampell says. There are valuable lessons for startups to learn here.

To make this point, he cites Apple — as an example of a company with a few marquee products that rakes it in on accessories.

“If you go to any Apple retail store, it’s clear how much money they’re making selling high-margin products like phone cases made by other companies like Speck,” he says.

On top of this, Apple folded deals with network providers into the prices of its mobile products to bring down costs. If you remember, sales of the iPhone only started to take off when the company slashed the price from $600 to $300.

“The thing is, Apple didn’t actually lower the price at all. They just said that if you sign up for a plan with AT&T your phone will be cheaper,” Rampell explains. “AT&T then would charge you more money, but the perceived cost of owning an iPhone went down.”

In many cases, optimizing revenue is all about structuring transactions with additional options so that people don’t believe they are paying more — they focus instead on the convenience, value and experience you’re offering them.

Think Like a Phone Company

Apple’s deal with AT&T can be generalized and emulated: Just bundle an incentive with a recurring billing product. When you do this, consumers are effectively buying down the price of your product (the discount on your product being the incentive).

When you combine your product with another made by someone else, you end up making more while also needing to develop less. You’re just cross-linking and taking advantage of your checkout page real estate.

This tactic can be especially helpful for startups who don’t see any payments at all from their users. In fact, that’s how TrialPay got its start. It worked with companies where 99% of customers wouldn’t pay for a product, no matter how they were segmented. What it did was substitute a different product that would draw demand that the company could then exploit.

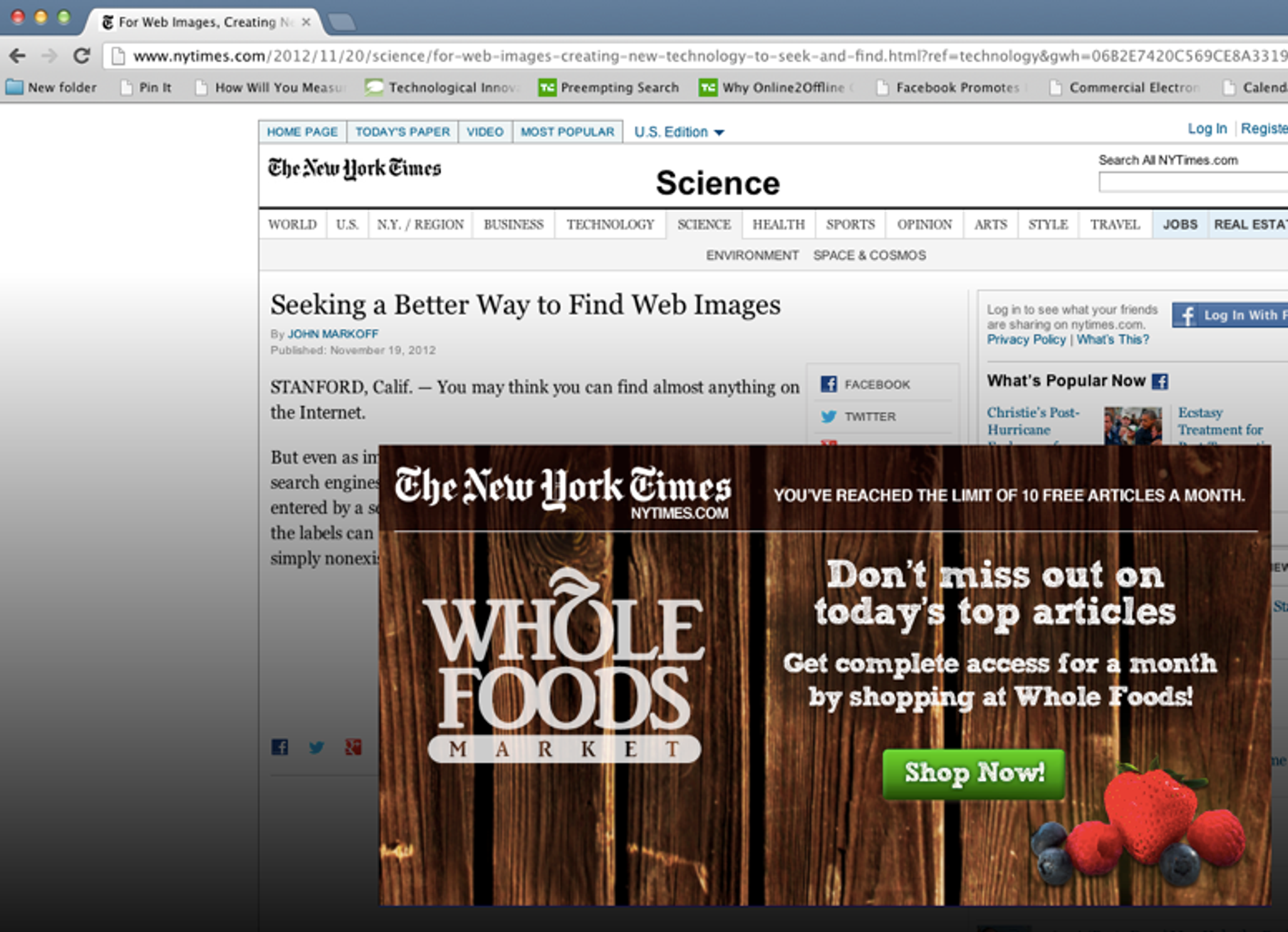

One of the best examples is The New York Times. No matter how little the newspaper tried to charge, most readers wouldn’t pay for online content. So TrialPay embedded a better offer in its subscription flow: Visit Whole Foods’ online store and you can read The New York Times online for free.

As anticipated, most NYT readers also buy groceries, and more people need groceries than need to read the news. At the same time, Whole Foods was willing to pay for new customer referrals. By playing middleman, the newspaper could extend its revenue without getting more customers to buy its product — they could buy something else instead.

Be Selective About Incentives and Discounts

Amazon famously drove up its purchase volume by offering free shipping for all orders over $25 (now $35). But what’s an equivalent offer for modern startups that don’t offer physical products (and where free shipping makes no sense)?

Rampell has observed and tested a number of different options, but found three strategies to be particularly effective:

- Never ASK people for a “coupon” code. And get rid of your “coupon” field in your checkout flow. You’ll lose customers and revenue if you ask them to go hunting on Google for coupon codes. (More on this later.)

- Contact information has long-term value if you can get it. It’s worth turning off some users in order to get more data (e.g., email addresses) for other customers that can help you segment them going forward.

- If you don’t have anything to offer as a bonus, find a complementary partner that you can work with to offer something unique.

Free shipping is an attractive incentive because it appeals to anyone who is getting something mailed to them. In order for incentives to drive more conversions, they have to relevant to your audience.

“In one test, we told customers that if they paid for something with PayPal, they’d get a gift certificate from the Gap or whatever the company was,” Rampell says. It turned out that companies would readily give away gift certificates (if well-qualified, like after a higher dollar purchase) in exchange for new customers. Checkout rates increased by 15% to 25%.

One incentive that definitely isn’t worth it is asking for promo codes.

When you ask your user for a coupon code, you’re basically giving them an IQ test asking 'Are you dumb enough to pay full price or would you rather pay less?'

If they think they can find a discount opportunity that’s just a click away, they will go hunting at your peril. Playing into this game doesn’t just dilute your income with unnecessary discounts, Rampell says, it sends people out of your checkout flow where they might get distracted and abandon the process altogether.

All that said, discounts aren’t inherently bad. In fact, they can be incredibly effective if you position them correctly. For example, instead of asking for a promo or coupon code, provide a field in your checkout flow labeled “gift certificate” or a referral field where you ask people how they heard about your company.

“This way, you can still apply a discount, but you’re not sending people out to proactively search for them on their own,” Rampell says.

When he and Dixon launched their DidTheyReadIt email tracker, only about 1% of users converted to paying customers. So they tested discounting in waves, offering 20% off and then escalating.

“For products with marginal costs close to zero, there’s no downside to acquiring customers at bargain basement prices,” he says. “We’d give away a very, very large upfront discount, but when the service started to recur, it would be at full price.” This ended up working quite nicely.

Finally, wherever possible, incentivize your customers to provide as much contact and data about themselves as possible. This can be challenging — and you risk turning off at least some portion of your audience — but it can pay major dividends going forward. To make it more palatable, have them volunteer this information in exchange for a desirable bonus, either from your company or one of your partners.

“This is pretty common for enterprise software companies,” says Rampell. “You can offer a customer a free trial and then say we’ll extend that trial an extra two months if you give us your phone number or address. That can be very powerful to provide them better service and sell them more products in the future. At the very least, you’ll be able to contact more customers more often.”

As a final word on incentives: Never offer too many.

“Look at something like GoDaddy. Their checkout flow is cluttered with all kind of add-ons and cross-selling and it takes you about 20 minutes to pay,” says Rampell. “There’s a very fine line here. You could say, 'Oh we’re a pure company that doesn’t cross-sell or upsell,' but sometimes when you do that you can’t cover your costs either.” And when done right, like at a movie theater, customers enjoy the movie more with popcorn and drinks, and the theater makes more money.

There are two extremes, and you have to figure out where your company belongs on the spectrum. You don’t have to nix all partnership and bundling opportunities to come across as pure and sincere. You also don’t have to settle for a cluttered checkout experience in order to run comprehensive experiments.

“The real key is to test enough strategies in a way that gives you the quickest sense of what you can or cannot charge — that doesn’t drive customers away,” says Rampell. “Every pricing option you throw out there should be geared toward getting more information about who customers are, what they want, and what they are willing to pay.”