In 2011, ClassPass founder Payal Kadakia had just joined startup accelerator Techstars. Within months, she’d been on the cover of Inc. Magazine and featured in Mashable, Business Insider, Gigaom and most every tech and business blog.

She should’ve been living the startup dream. The only trouble was, no one was using her product.

Spoiler alert: ClassPass has certainly found its footing and is off to the races. But it took years of pivots (three major product iterations), rebrands (from the original Classtivity to the now-famous ClassPass), and good old-fashioned conviction to make it through.

Now, Kadakia advises founders to constantly return to on one all-important question: what problem in the world are you trying to solve? With her eye steadily on the mission, and a laser focus on only the most critical metrics, she guided her company from a near-bust to a $470 million game-changer. In this exclusive interview, she walks through that trajectory, sharing the nine key lessons she’s learned on how startups building a marketplace can find product/market fit.

1. Shorthands help get you known, not grown.

ClassPass, then Classtivity, started not as the membership service it is today, but as a way to simply search for classes. “The first iteration was really inspired by what was already going on in the market,” says Kadakia. “There were models like OpenTable and Zocdoc already, so I thought, ‘What if I applied this to classes? As a dancer myself, I wanted to build what I wanted as a consumer: a way to make it easy for people to find and book fitness classes. It seemed like the search engine model was a good way to achieve this.”

There are advantages to this approach, which creates an easy shorthand when reaching out to investors. “People had seen the success of these other companies providing a search engine for their offerings — in those cases, restaurants and doctors. People knew that this was a problem, and that there was enough of a market there,” says Kadakia. “That early enthusiasm gave me the resources and momentum to start building, but what I didn’t initially think deeply about was whether this solution was what my customers wanted.”

When launch rolled around, all eyes were on the hot new company and press flooded in. “But I had to remind myself that it was not an indicator of what was actually going on with our company, because at that point we were making no reservations,” says Kadakia. “With no reservations, I wasn’t making an impact on people's lives. I obviously had no business either as my entire business model was built on volume.”

Kadakia found herself in an untenable position: Thanks to Techstars, she was able to raise additional capital. But when it came to doing something with that cash, she was stuck. “I remember at that moment thinking, ‘Well, we're not actually doing anything. And if we stay like this, we're not going to be able to solve the problem. We're never going to be a big company making a difference in the world,’” she says. “We treaded water for a couple of months, tweaking buttons here and there and moving forward on some feature enhancements. But we were so off on the actual product that after two months I thought, ‘What are we doing? We need to really reassess this.’”

It wasn’t until an advisor got her to press pause, that she rediscovered her agency — and reclaimed her role in Classtivity’s journey. “I thought, ‘This is on me. I'm the leader. This company is going to make or break with me.’ I knew that if we weren’t moving toward something and being inspired by what we were doing, it was on me to start changing the grain and figuring out what we could do to switch up the product and achieve our mission,” says Kadakia. “So, I walked into work that day and told the team we had to go back to the drawing board. We had already put more than a year into the company, but I knew we had to try a new product. We needed to focus less on sticking to be understood — the story in the market — and more on understanding the problem we wanted to truly solve. And so began the first of several reinventions on our way to product/market fit.”

2. Gauge if you’re powered by steam or wind.

Kadakia started to ignore outward measures of success — what she calls false signals like capital raised, press, social media followers — in favor of a more meaningful signal: customer behavior. “If you focus on all those other things, you’re not fueling your company. You’re just gliding on tailwinds supplied by other sources. You’re reliant on energy that you’re not creating,” says Kadakia. “That may last for a while, but not forever. It’s hard to expect you can scale that way. Instead, return to why you started your company — those actions generate steam when you rev that engine. That’s where we focused our energy, not necessarily what would help us raise money or our profile. That became more superficial.”

The team went back to basics, talking to studio owners and trying to better understand what the customer really wanted. “When I got back into a studio, it came back to me. The reason I started this company is because I've been a dancer my whole life and I truly believe in what being active can do for people's lives,” says Kadakia. “And yet I wasn't doing anything for anyone's life without getting them to class. Yes, we were getting press. But I think the best entrepreneurs keep asking themselves, even when people think they've made it, ‘How can I keep impacting people’s lives?’”

What Kadakia and her team learned while soul-searching and gathering feedback was that simply knowing what classes are out there isn’t enough to motivate someone to walk into a studio. They needed more of a nudge. “We realized that many studio owners were giving a class for free. We had already built the technology to help people get all this data about classes. So we thought, ‘What if we just packaged it differently?’” says Kadakia. “We built a product called the Passport. For a flat fee, customers could take 10 different classes at local studios in a 30-day period. We hypothesized that, having invested up front, users would be more motivated to use the product. So we decided to launch and see if we could fuel our own path forward.”

3. At the start, do as much as you can manually.

Conventional startup wisdom says lay the groundwork to execute repeatable actions with technology. But don’t just follow that advice by default — check yourself to make sure you’re not overbuilding your technology, making it your end goal rather than your customer. A good way to press pause is step back and manually do what your technology normally does. “One of my favorite things about this time is that I didn’t let technology drive or hinder my product development,” says Kadakia. “We started building the product to do what it needed to for the customer. Most of the stuff on the backend was either done manually or didn't work. Someone would make a class reservation at this time, and I would get an email. Then I would go and make the reservation manually. Instead of building out the perfect booking system, what I needed to figure out at this point was what was going to motivate people to make a reservation and then go to class. The rest simply didn’t matter. ”

By taking on part of the reservation process manually, Kadakia internalized customer behavior in a visceral way. “That’ll happen if you’re doing the equivalent of sending confirmation emails for every customer. It helped me realize that technology is crucial, obviously. But it’s still just a tool to get your solution into the world. Your software is not your answer in and of itself. Your insights into customers are your solution,” says Kadakia. “The product became a product because of the insights and the learnings we got from directly interacting with our customers — on top of the technology. But we had to guide the technology with our thinking and our learning. Those many days I spent inputting reservations manually turned into another valuable stream of customer insights. I quickly learned not to book reservations right away, as half of cancellations came within 15 minutes of booking. That became an important part of the design of our cancellation policies.”

In the early days, periodically find part of your product and do it manually. Allow that to help you get out of the technology you’re building and into the head of your customer. That might mean taking a turn on the customer support desk. Or revisiting your usage data. “Just make sure you don’t fall into the trap of thinking technology is going to answer everything,” says Kadakia. “A lot of founders think, ‘Now I’ve hired a developer who’s going to answer all my questions.’”

4. Honor the transaction above all — and let it break you.

Kadakia emerged from those difficult early years with a new mantra: if you can't get the transaction to happen, the technology isn't going to solve it. Instead of spending a week or two redesigning the website for a new offering, she would just send out a simple email (see below) to see if customers were interested. “You get very good at figuring out how to communicate with people. If someone's not willing to buy something when you tell it to them to their face, they're not going to buy it through a pretty website.”

In its second iteration, armed with a bare-bones website, the company had taken a huge leap toward product/market fit. The Passport launched in December 2012 and was a quick hit. Reservations were finally coming in — 20,000 in the first 6 months alone.

And Kadakia had learned a crucial lesson: if you can only have one, a good offer beats slick web design any day. “We built the first product to make it so easy to find a class. The second product we sold was a package with a deeper value proposition,” says Kadakia. “Even though it was hard to find a class, people did it anyway because they wanted to experience the product. People were excited about the idea of the Passport and of exploring workouts — and their city — for a month. It made me realize that the threshold for ease of use was simply seeing the classes and hitting “reserve” before a soft launch. The product is much easier to use now, but that wasn't part of our initial product/market fit. That came through feature enhancements that we made over time.”

As the Passport took off, the team had to contend with what Kadakia calls “champagne problems” — the site crashing regularly at noon, for example, when the booking window opened. But if the choice is between that and the crushing silence of zero users on your beautifully designed site, it’s a no-brainer. “Don't worry about those problems until they happen,” says Kadakia. “You know, in the beginning, people would say, ‘Oh, well, we need to build this thing to scale.’ But, honestly, let the site go down. If people keep coming back, it’s a pretty good sign that you’re onto something. If they don’t due to a brief technical lapse, it’s likely not just the tech; there’s a dangerous fragility with your business or business model.”

Early on, don’t worry about branding or your company name. We changed both many times. With marketplaces, it comes down to changing human behavior. What matters to me is getting someone to class.

5. Don’t overprescribe behavior.

A lot of founders try to predict every behavior their users might demonstrate, installing guardrails to guide every interaction with the product. But if you do that too early in your product’s evolution, you might actually miss out on observations that would put you on the fast track to product/market fit.

In fact, it was a common customer “cheat” that gave ClassPass its last major push toward the product it has made its name on. By this point, the Passport had taken off like gangbusters. But it was intended to be a one-time opportunity to sample classes. From there, the assumption was that users would find a favorite studio and join it.

What actually happened, though, is that customers found a way to keep using the Passport: signing up with different email addresses. “Our studio owners were emailing us, saying, ‘Hey, you guys promised us this was a one-time deal, that people couldn’t come back without paying us,’” says Kadakia. “From a tech perspective, we knew they actually couldn’t. The system was built for one reservation to be made at every studio.”

Kadakia quickly diagnosed what was going on — and gained one of the most valuable learnings in her startup’s evolution. “First we realized that people were being fraudulent and gaming the system. A natural response would be to fight fire with fire and gamify the system so people are incentivized to behave properly. But that misses a fundamental insight. Why were people so compelled to sign up with three different email addresses to keep access to classes. At the core of this action was that people loved variety, so much so that they’d create new email addresses to keep testing out studios,” says Kadakia. “With every transgression, return to the motivation or you’ll miss important insights. We knew that we needed to figure out how we were going to make a product where offering variety worked for the studio owners.”

The answer? A subscription offering. It was the final evolution into the ClassPass product that users know today. It launched in June 2013 as Classtivity ClassPass.

That evolution, though, wasn’t part of a carefully plotted product roadmap. It was a chance discovery, born of letting users play around in the product without carefully prescribed parameters. “Let behavior happen. We would have never discovered that variety was unbelievably important to people if we hadn’t done that,” says Kadakia. “Founders, at the end of the day, aren’t we all doing what we’re doing because we see a solution that doesn’t exist? If it existed, why would we be here? We're trying to start a new behavior in the world. There are things you can do to motivate people and make things easier. But you can't overprescribe it.”

Let your users "play" in your product. Don’t overprescribe or force a path. Build a sandbox, not a maze. That’s when you’ll spot the behavior that orients your product.

6. Kill your darlings.

By late 2013 — nearly three years in — Kadakia and her team had really found their footing. They understood how to get their customer to class and had built the product that customers wanted. The evolution would be formalized in early 2014 with an official name change from Classtivity to ClassPass.

But that’s not to say the changes were painless. Just as aspiring novelists are taught to cut cherished plot twists when they’re not working, founders, too, will have to ditch features and products that aren’t working along the way. Even ones they love. Even ones that they’ve invested months — or years — building. “Once we changed our name to ClassPass and officially launched the subscription product, we shut down the search engine. We got rid of the Passport product, too,” says Kadakia. “My engineer who had built the search engine for two and a half years was gutted. It was hard for him to let his hard work go.”

In the moment, it’s difficult to see why this is necessary. “You always think you're bigger than you are. When we first changed our name and shifted the product from Classtivity, we had done 20,000 reservations. It felt like a lot at the time. But now, we're closer to 50 million reservations made,” says Kadakia. “Who remembers Classtivity, or even this idea of a Passport now? In the halls of ClassPass, this idea of Passport reservations is a data field my engineers see every once in a while and ask, ‘What was this?’"

Still, feelings of loss or frustration at killing a project the team has invested in are real, and a leader needs to acknowledge that while confidently bringing people along for the ride. Kadakia’s best advice? Lead with conviction. If you don’t, you double your chances of failing. You may lose because you’re wrong or because you hesitated and others doubt you. “With the new subscription model, I didn't know it was fully going to work. I had to lead with conviction until I had the data so others could really subscribe to my decision,” says Kadakia. “Once the data came in, it was ten times easier to convince the team. In the Passport offering, the numbers were too far off. There was no way forward. We had a target metric internally that 75% of people who had given something a positive rating would go back to a studio. But we only saw 15% — and 15 to 75 is way too big of a gap. If it had been closer to 60, maybe we could have gotten an extra 15% through product optimization or communication. But it was so far off that we had to acknowledge that people just didn't want to do what we were trying to get them to do.”

Even with data, be prepared to battle inertia, though. Kadakia clearly recalls the day she told her team they needed to move to a subscription model. The idea was greeted with little enthusiasm. “We had something that was kind of working, and people have a tendency to want to keep working on what you currently have,” says Kadakia. “So they started throwing out patches to the existing product, like sending more emails or trying new marketing campaigns. But what was needed was a more wholesale, but calibrated shift. In practice, what that looks like is, first, acknowledging that not everything is broken, and second, that you’ll work through the changes together. The truth is that I wasn’t entirely sure the new strategy would work. My conviction was important, yes, but camaraderie through change was more critical to the team.”

7. Find — and flaunt — your metric to rule them all.

In the early days, when Kadakia didn’t have numbers to guide her, ClassPass was a labor of conviction and commitment. Once product changes began driving an increasing volume of users to the site, though, one all-important metric emerged.“Once the product started working, the number of reservations per person became the clearest representation of true north,” she says. “That was another key development: finally realizing that the number of reservations per person was the metric that was the heartbeat of our company. It was when we hit 150 customers in our second month. That number seems small to us today, but this group created a new habit of going to class every week. I remember that moment, when I thought, ‘This is the number. This is the only number that matters. I’d rather have 150 people using it weekly than 1,500 attending the occasional class.’”

For ClassPass, that reservation number touched every key indicator for the business. It offered insight into churn, revenue and engagement. It represented how happy studios were with their experience. And most importantly, it became a quick snapshot of the impact the company was having.

In a search for your “golden metric,” don’t just default to the traditional ways of measuring a business. Revenue, the go-to metric for some business models, didn’t work for ClassPass. “If we have a lot of revenue and no one is going to class, that's a problem — or will be very soon,” says Kadakia. “Site traffic, too, was never a reliable indicator of success. If I’d measured that alone, I would have thought Classtivity, the search engine, was working. Whatever you land on, determining your most valuable metric or two is a crucial step to understanding, and building, your business.”

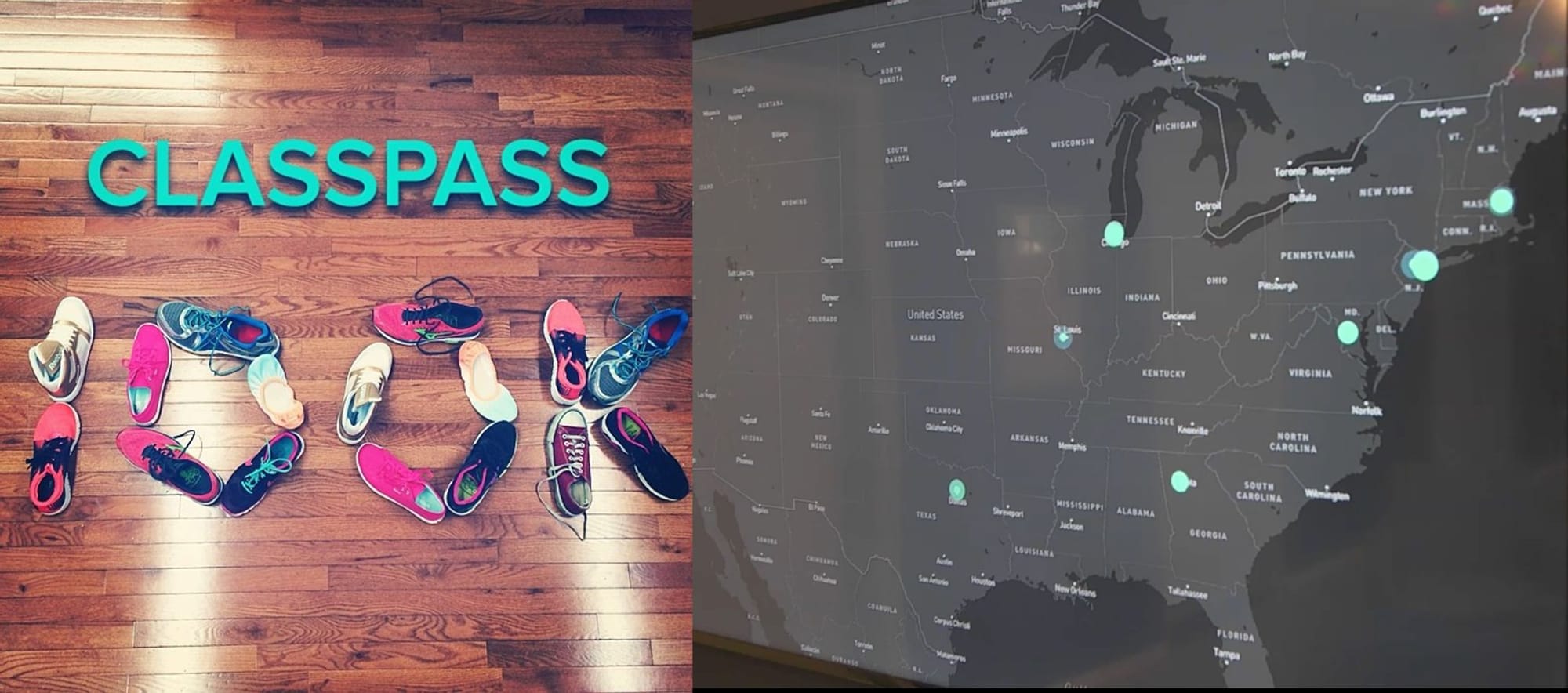

Beyond the business benefits, knowing — and articulating — your key metrics goes a long way toward building morale, and a mission-driven team environment. “I remember when we hit 100,000 reservations, a few months after we launched ClassPass. We have a nice photo. We had around six employees then, and we all brought our sneakers in and we wrote 100K on the floor and took a photo,” says Kadakia. “The reservations number is still front and center around the ClassPass offices, where no employee can miss its importance. We actually have a world map on the wall, and every single time someone makes a reservation it blinks. It’s a fancier display of what we’ve held true for some time now — it keeps us rooted in the right reality.”

8. Abide by Fogg’s equation for user behavior.

Even now on the other side of ClassPass’ product/market fit, Kadakia still remains a student of the mechanism to get there. “There’s a behavioral design professor at Stanford, BJ Fogg, who has developed a model that says for any behavior in the world to occur, you need three things to happen at the same time: motivation, ability and a trigger,” she says. “Motivation can play off of many things, like pleasure or pain, hope or fear. Ability refers to how easy it is to execute the behavior. And the trigger is that final impetus to click or buy.”

It’s easy, though, to get stuck on one or two of these factors, and build off of an incomplete equation, thus missing the big picture. That’s exactly what Kadakia realizes she had done with the original Classtivity. “I really built everything on the ability. I was just making it easier and easier. What I hadn't done was build something that was motivating for people,” says Kadakia. “Don’t underinvest on the motivation factor, especially because it’s frequently the hardest to pin down. Technology can help build the ability. And marketing can help build the trigger. But motivation really comes from understanding your customers.”

But even when it came to building for ability, she was coming at it the wrong way. Classtivity made it easier and easier to find classes, but it didn’t address the greater barrier: actually getting to class. “People would find a class. Then, then doubt crept in. People would think, ‘I've never been to a bootcamp. It's $30. It's in this location, and it's at this time. Oh my god. I think I might be busy. Forget it,’” says Kadakia. “When it comes to ability, think not only about capability, but about how many brain cycles your customer has to go through.”

For starters, the ClassPass product separates the purchasing decision from the decision to go to class. “You buy it at a completely different point. Then the next day, when you're ready to go to class, we've made you think, ‘Well, I have credits, so I should use them.’ People always tell us they feel like a kid in a candy store,” says Kadakia. “The product minimizes the number of decisions users need to make at one time, thereby reducing friction and increasing ability.”

The trigger is in many ways the easiest to nail, because it’s the easiest to test. “The key question to ask is how are you asking users to take the action you want them to? Email? Texts? Advertisements? “We've done a lot more in this area in recent years. Reminders such as ‘You haven't gone to class’ or ‘Your class is coming up in 12 hours.’ Those are triggers,” says Kadakia. “Also, one of the best triggers is the post-class endorphin high itself. You’re going to walk out of class thinking, ‘I loved this. I can’t wait to go back again.’ Not every product lends itself to riding the endorphin wave. But each product has momentum-driving moments where users’ engagement can more easily trigger the next action you’d like them to take.”

9. You’re still launching.

ClassPass’ subscription offering was the key. It unlocked the growth that has made the company a $470 million company — and fulfilled Kadakia’s dream of getting people into the studio. But she is quick to note that she wasn’t, and isn’t, done. Customers’ needs change, markets evolve, and product/market fit is dynamic.

This is, in part, why Kadakia has never been one to do a splashy product reveal. In many ways, ClassPass never really launched. Classtivity’s search engine rolled into the Passport which rolled into the subscription product we know today. “A lot of people launch before knowing they have product/market fit, and I think you need to be careful of that,” says Kadakia. “One of the things I've learned is that every customer matters. Every time they have a first experience with your product, it's really important. You launch to customers every single day.”

Thinking of launch as a continual process also ensures that your product doesn’t become stale. In its most recent evolution, ClassPass moved from a classes-per-month subscription to a credits-based subscription. “It’s another step to support our mission of inspiring people to do things that make them feel fulfilled. We just released a ‘wellness’ offering so people can now book meditation classes, massages, and cryotherapy through their ClassPass app. We wouldn't have been able to do that if we didn't move to credits.”

Bringing It All Together

According to Kadakia, all of the following movements toward product/market fit should continuously bring you back to one question: what problem in the world are you trying to solve? In search of the “fit” part of product/market fit, founders can veer away from their first principles around the problem they want to solve. To avoid that, don’t mistake external indicators — like press mentions, financings or social media followers — for product/market fit. Early on, do part of your product manually in order to fully understand the customer experience while it’s still easy to improve. Focus your efforts on completing transactions and don’t worry if volume breaks what you’ve built. If users love your offering, they’ll be willing to wait for the site to work. Don’t overprescribe user actions. Instead let them explore your product: you may be surprised by how they intend to use it. If you want to influence user behavior, use Fogg’s equation. Be willing to kill your darlings and know you’ll always be iterating to maintain product/market fit.

“I liken my path to product/market fit to throwing a number of darts in the same direction. I don't believe in throwing them at the same time. I just believe in throwing one and as quickly as possible moving to the next dart. I subscribe to rapid iteration,” says Kadakia. “But when you get close to the bullseye, dig in. That’s the time to invest in your technology, map out your product refinements and optimize your website. Until then, though, your job is to spend your time and resources figuring out what your customer wants and how you can affect a behavior change to ultimately solve the problem you set out on. Do that, and you’ll build a muscle that won’t just get you to product/market fit once — it’ll ensure that your product stays relevant and your mission gets accomplished. We’ve never been closer to the bullseye than now. But I still have a fist of darts ready to let fly.”

Photography courtesy of ClassPass.