It’s summer 2011, Apple’s latest release is the iPhone 4, and Facebook and Angry Birds top the charts in the App Store (which is only three years old). Two Bridgewater software engineers and a serial entrepreneur meet for dinner in NYC, musing about the future of the mobile industry and their own startup ambitions.

A chance introduction at TechCrunch Disrupt brought the three together. Bill Magnuson and his colleague at Bridgewater at the time, Jonathan Hyman, were looking for a business to start. Mark Ghermezian was working on a social network for app developers called Appboy and wanted some help rebooting it.

Over dinner, they discuss how they might help mobile developers monetize their apps — beyond simply pocketing $1.99 after a download — with a platform to engage users across different channels. So they set out to start working on Appboy 2.0 together.

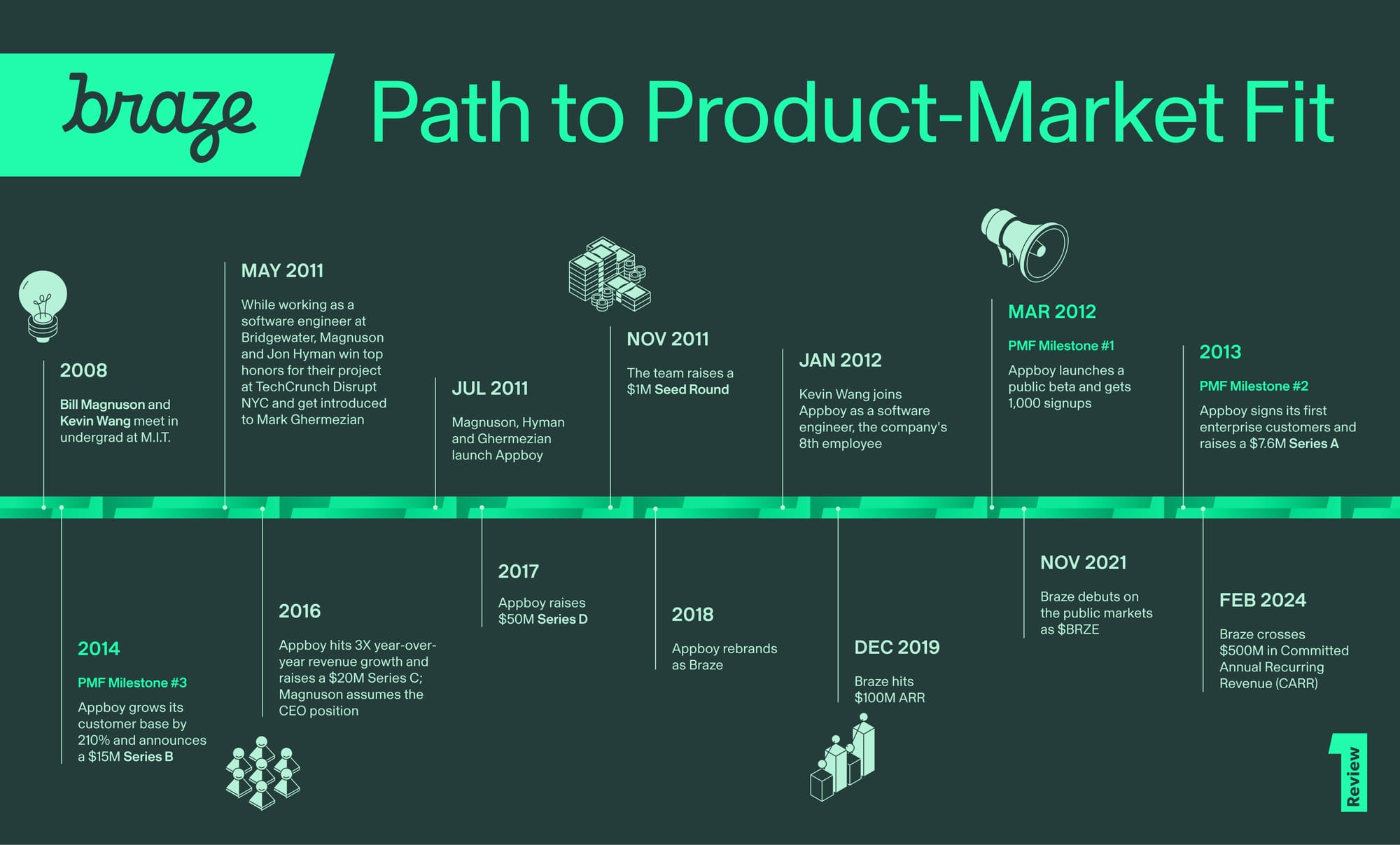

Over a decade, a rebrand to Braze and an IPO later, $BRZE now pulls in hundreds of millions of dollars in Committed Annual Recurring Revenue (CARR) and has a multi-billion dollar market cap.

Their bet on mobile seems like an obvious one in retrospect, but at the time, the notion of “mobile marketing” was unheard of — software developers were still the ones running their apps’ growth, relying primarily on the App Store as a distribution engine. The consensus path to make any real money in the mobile industry was to build for gaming apps. Existing enterprises like banks and retailers hadn’t yet built out their presence on mobile.

Braze’s path didn’t come without growing pains and hefty skepticism. Many of Braze’s first 1,000 beta customers churned — because most of their apps died. And it wasn’t until Braze’s Series D, six years after the company’s inception, that the founders received more than one term sheet.

“The market wasn't ready for us to sell to it yet,” says Magnuson, who was originally CTO and is now Braze’s CEO. “Our best answer to ‘why now?’ was to get a multi-year head start on something we had strong conviction in. But not everyone agreed with that. In the early days, it was sometimes difficult to maintain that full conviction because of how long it took.”

But the Braze team held firm on their vision and built a horizontal engagement platform before the market had fully materialized and before their ICP even existed.

In this exclusive interview, Magnuson is joined by Kevin Wang, Braze’s 8th employee and now Chief Product Officer, to share all of the early instincts and decisions that led them to the floor of Nasdaq.

Seeing early potential in mobile

Magnuson always knew he wanted to start something. He grew up in rural Minnesota during the dot com boom — the computer in his parents’ basement was his gateway to the rest of the world. “Being able to build new things with new discoveries is what makes me tick,” he says.

He went on to study computer science at M.I.T. Shortly after graduating in 2009, Magnuson got his first glimpse of the mobile wave while interning at Google, where he worked on a visual programming language for Android apps and finished up his master’s thesis.

But most people seemed to think that the business potential for mobile apps was murky. “People were still nervous about putting a credit card into a mobile app. This concept of digital purchases was brand new,” says Magnuson. “In the early days, this held people back from thinking about building businesses for mobile, because there were no recurring revenue streams from mobile app users. All the money you were ever going to make from them was right up front, when someone purchases an app.”

Still, Magnuson suspected mobile phones had paradigm-shift potential. “I could see that the energy was there. I wanted to make sure that as the world was going to change with mobile, I would be part of it,” he says.

After Magnuson left Google, he took a brief foray to Bridgewater Associates to take care of some personal finance goals so that he’d be ready to take the leap to start a company in the mobile space.

“I felt like mobile was going to be as important as the dot com boom in the nineties. And I knew that I wouldn't be able to forgive myself if I was at a hedge fund on the sidelines as the whole world was changing,” says Magnuson.

At Bridgewater, he met Hyman, another software engineer who had entrepreneurial dreams of his own.

A chance meeting connects the founders with the idea

Magnuson and Hyman had been living near Bridgewater's HQ in Connecticut. In May 2011, they traveled down to NYC to participate in TechCrunch Disrupt for a totally unrelated project.

The demo they presented was a plugin for Gilt, the flash auction site, that allowed users to hold items in their cart and let other shoppers bid on it. Hyman thought of the idea after his girlfriend successfully snagged a trendy pair of shoes in her cart on Gilt, but then no longer wanted them for herself. “It was an arbitrage opportunity on top of a place where you were allowed to hold inventory for free,” says Magnuson.

The pair wound up taking home top honors at the hackathon, which caught the attention of some aspiring entrepreneurs and VCs in attendance. But it was a run-in on a busy Manhattan intersection that would lead them to their third co-founder — and a great idea for a mobile startup.

On their way to present the demo on the final day of Disrupt, they bumped into Bipul Sinha. At the time, he was a partner at Lightspeed Ventures (he’d later found Rubrik) and recognized the pair from their winning demo. Sinha insisted Magnuson and Hyman meet Mark Ghermezian, a serial tech CEO who was living in Houston.

In short order, Ghermezian flew up to NYC to meet Magnuson and Hyman for dinner. He’d been working as an oil and gas CEO at the time, but he had a side project called Appboy, a website for app developers to interact with their users, that wasn’t gaining the traction he wanted.

Magnuson and Hyman saw the potential of the idea immediately, and in the pair, Ghermezian had found the technical talent he needed to overhaul the platform. “The idea for the company was born from that original idea for Appboy, which is the fundamental business insight that if you want to build a sustainable business, you do that on the back of high-quality, long-term relationships. And if you want to build a relationship with someone, you should pay attention to people when you meet them,” says Magnuson. “We wanted to take those very basic human and business concepts and translate them into software that would help mobile app owners.”

After that dinner, they all agreed they were ready to take the plunge. “We pretty much decided during that meal that we were all going to quit our jobs and have a go of it. We knew what we were going to work on right out of the gate.”

Building a prototype for a fledgling market

In the following weeks, Magnuson, Hyman and Ghermezian all moved to NYC and started sketching out product specs and an early object model on whiteboards.

They had a strong opinion for what the product should be from the outset. “The questions we wanted to answer were: How can we help someone building a mobile app stay connected to their users and encourage ongoing usage? And what do we want to know about the user to drive more relevance and value? That shaped a lot of the early product design,” says Magnuson.

“So we knew we needed to be cross-channel from the very beginning,” he says. “Unlike a lot of companies that are built to only send push notifications or do email marketing, we were trying to solve a business problem.” The first product offered these four message types:

- Push notifications

- Newsfeed (this was pre-Facebook newsfeed)

- Slide up message

“Our vision for our product was fully incorporated into the actual mobile apps. So that meant it couldn't just be an email or push notification coming in over the top. It actually had to be part of the look and feel and the interaction of the app,” says Magnuson. To brush up on the latest in mobile UI, Magnuson stayed active in the mobile app ecosystem that he’d been involved in since his days at Google, working with app developers and going to meetups.

But many folks he spoke with didn’t seem ready for the product the team was building. Most app developers at the time relied solely on the App Store for distribution. “I remember going to meetups in 2011. Our tagline was ‘turn your app into a business,’ but people were skeptical because a lot of app developers at the time were just hobbyists who were building things and throwing them into the App Store,” he says (think of apps from this era like Run Pee that had a clever idea but no business model to speak of).

Some who played with the early Appboy product flat out told Magnuson that they didn’t want a customer engagement platform, and the $1.99 they got from the App Store purchase was enough. “That was an interesting example where we had to take that and say, ‘That customer feedback is wrong.’”

Our conviction was that the mobile app ecosystem would turn into a thriving economy with great sustainable businesses. But no one was there yet.

Because the team was building for a future state, competition didn’t inform the early product iteration. In fact, Magnuson didn’t perceive any direct competitors in the beginning at all. “I couldn’t have even told you what ‘CRM’ stood for when we started building the company,” he says.

Raising slowly

Given the lukewarm interest from some mobile app developers, the team knew there wasn’t extensive selling to do right away. So they focused most of their efforts — and hiring — on engineering and product development (the early team was an “amorphous engineering blob,” in Magnuson’s words). Beyond raising a Seed Round in November 2011 and an expanded Seed in March 2012, Magnuson felt no rush to stock up on follow-on capital.

“We didn't intend to raise a tremendous amount of money in our early rounds because we knew the market wasn’t mature enough for us to go and rapidly scale a GTM machine,” says Magnuson.

The raise-to-scale-fast approach eventually proved disastrous for a few early competitors. “They’d raise a $10 to $15 million Series A and then burn themselves out. Despite having more resources, they were effectively trying to push on a rope. And we had that visibility into our market. We also had the patience to understand that.”

Assembling the early team

Around six months into building, Kevin Wang entered the picture. He and Magnuson were fraternity brothers at M.I.T.

Wang had been working as a consultant at Accenture in the energy trading industry with clients who relied on old-school enterprise tech. “Kids don't grow up thinking, ‘Man, I really want to do enterprise SaaS,’ but from working with this technology and seeing how successful it was, I felt that there was a huge amount of promise,” says Wang.

Like Magnuson, he also felt that mobile was going to shake up the business world and wanted to find a way to bring mobile to enterprises.

So when Magnuson and Appboy’s first business hire, Spencer Burke, were passing through Boston on their way back from a ski trip and met up with Wang, Magnuson pitched Wang to join. It was exactly the opportunity Wang had been looking for.

Magnuson wanted Wang for his double threat coding chops and neuroscience smarts. “We were thinking about the science of human relationships and how to connect with resonance and relevance. His cognitive sciences background along with the ability to build and execute code in the early days was particularly valuable to us as we were growing.”

Wang then moved to NYC where he was the 8th employee — the team worked from one of the first WeWorks in existence in a tiny room with bare concrete floors in the Meatpacking District, where Rihanna’s “We Found Love” blared on the speakers. “I remember thinking, ‘This is very different from big consulting. The people are way smarter and this is a much scrappier environment,’” he says.

Churning customers to find the right ones

In fall 2011, after several months of building, Magnuson and the small Appboy team rolled out a private beta to some 40 app developers across multiple categories. It tested well enough for apps with large user bases that they decided to do a public launch. In March 2012, they released a free SDK and announced it on TechCrunch — and netted 1,000 beta signups within two weeks.

But those initial signups proved to be ephemeral. Few wanted to pay for it, and over time, many of those apps didn’t make it.

“It's a funny number to look at because today, we only have a little over 2,000 customers. Out of those 1,000 beta signups, I don't think we have any customers today that came out of that initial set,” says Magnuson.

Turns out the market still wasn’t ready for this kind of product yet. “A lot of mobile app developers were hobbyists. They weren't willing to spend money. And if they couldn't make money on their customers in the long term, there was no reason for them to pay someone to be able to engage them in the long term,” he says. “That created some interesting early friction. Our ideal customer just hadn't emerged yet in the market.”

Wang likens the sales approach in the early days to building a huge net to catch as many fish as possible — rather than precision-fishing with a rod. “We didn't just have conviction in a pond — we had conviction in a huge ocean. Despite the lack of paying customers actively pulling us in any direction, we were very focused around that core idea and the market that we were increasingly sure was going to emerge.”

A new ICP emerges

Then slowly over the next few years, just as the founders had suspected, popular mobile apps started to mature as businesses, and established businesses launched their own apps. Broad adoption of mobile and a maturing market had created the right kinds of customers to start selling to.

And with that shift arrived a new type of marketer to manage a business’s growth on mobile. “We had to grow up with the mobile app economy and these new ways of organizing marketing teams,” says Magnuson. “It was interesting to be at the convergence of an entirely new craft and set of skills to run a marketing team.”

The ideal Appboy customer began to crystallize. “We found that early growth teams of mobile apps were our ideal customer. They were a pretty tight-knit community because they were forging a new, more data-driven and experimental way to approach marketing,” says Magnuson. “So we looked for those teams and those job titles.”

To find marketing teams that would be a good fit, the team pressed on outbound sales — founders included. “We would occasionally pick up a good warm lead by presenting at a meetup or conference, but we didn't have any meaningful budget to spend on broader demand gen,” he says.

But they still had to be picky. “One of the easiest qualification questions in the early days of the sales cycle was asking a customer how many monthly active users they had. Shockingly, a lot of them didn't know,” says Magnuson. “They knew their downloads, installs, app store chart rankings, but no one was paying attention to what was happening after day zero of the install.”

And it still took some pitching to show those customers what the product could do. “We had to paint the vision for people. It was a direct motion and a lot of us were involved in it. The adage that everyone needs to be a seller in the early days was absolutely true.”

We had the patience to understand that there were exogenous factors that we could influence. So we’d go to a meetup and encourage people to think about their app or run their marketing team in a certain way. We had to train our customers to use our software.

The team’s conviction in building a horizontal product proved to be a wise bet, and they began to sign customers across industries. “Our early customer base was a mix of online retailers trying to drive incremental purchases, and then early mobile subscription businesses,” says Magnuson. “We had delivery and dating apps, even some in gaming. So as a result, most of our early customers had businesses where real-time messaging was non-negotiable.”

Wang notes how some marketing teams’ early experimentation with mobile campaigns created a survival of the fittest competition. “If I’m running a much better marketing team than you are and we have a similar brand, I’m going to win, and I’m going to win really big,” he says. “As a result, there’s some powerful natural selection in the marketing world. Once the first crop of brands out there started to use products like ours, there was intense competition in the market.”

That’s because many of those marketers recognized similar signals from the beginning of the dot com boom. “Especially in the early 2010s, marketers remembered how the dawn of the internet was a massive sea change that was really scary. If anything, they were overly jumpy to hop onto the next paradigm, especially once it was working,” Wang says.

Creating feedback loops to sharpen conviction

With a roster of customers spanning industries and with several real businesses (and not just “hobbyists”), the team finally had an avenue for meaningful feedback.

“A lot of our development in years two and three was about cutting early scope that we had built, and then deepening the things that survived through that,” says Magnuson. “So we removed the editable user profile and the user feedback module entirely. But we also allowed that profile to be much more comprehensive and flexible behind the scenes.”

Wang likens the coalescence of the mobile market in the early 2010s to the rise of AI now. “Every week we were crystallizing more and more of the way that we thought that the world was going to be. There's some interesting parallels to where AI is today. People still don't know what's going to happen.”

What the customer feedback did wasn't necessarily giving us new ideas about new places to build, but it told us where to focus and shift in those first few years.

Graduating to enterprise

“We had a distinction in the early days between the mobile titans, which were the mobile apps that were growing and scaling quickly, and the enterprises that were trying to build a mobile presence. We were trying to build for both,” says Magnuson.

As big enterprises like banks started to build out a mobile presence, the team already had a wedge — because they came with an established business model. And the ICP of the early mobile adopter was often working within an enterprise marketing team.

Appboy found like-minded customers in the retail industry. “They were leaning into mobile as a place that people would do commerce in the future. And they knew that if they could engage customers in real time with higher relevance, they were going to drive more purchases,” says Magnuson.

Wang remembers the moment several years after founding when Appboy’s traction with enterprises really clicked. “They were all using Appboy in the same approximate way, which was the way that really aligned with our vision for where the world was going,” he says. “This is where we need to be. These are the buyers. We've got three of them right now, but 10 more conversations next week, it's going to be 100 the week after.”

The benefits of staying horizontal before the market grows up

In the long run, building a mobile product for all industries proved to be the bet that led Braze to breakout growth.

With a fully baked mobile market, Braze’s growth soared. In seven years from launch in 2019, Braze cleared $100m in ARR, and then $200m in 2021. In late 2021, Braze filed for an initial public offering. Today, Braze serves over 2,200 customers worldwide.

Meanwhile, their gaming-focused competitors started to crumble. “From 2012 to 2015, probably 85 to 90% of SaaS businesses in mobile were focused on the gaming industry,” says Magnuson. “So we stayed focused on building a product that would be widely useful across all different verticals.”

That turned out to be a fatal decision for gaming-focused companies. “When the market did come together, we were already there with a diversified capability. And everyone else actually had to spend time pivoting away from gaming — and some of them never managed to actually complete the pivot,” he says.

To this day, there’s no one biggest piece of the customer pie. “When you look at Braze today, actually, our largest single vertical is only around 21 to 22% of our revenue. And we have a highly diversified customer base across a whole bunch of different places.”

Founders building ahead of a market curve: Stay patient

In reflecting back on the journey to get here, Wang and Magnuson stress the need for founders — especially those eyeing a nascent market — to settle in for the long game.

It’s hard not to set expectations for flashy and fast progress when every buzzy new startup seems to hit staggering ARR in record time. “A lot of people fall for the headlines of this or that acquisition happening quickly and in the early years,” says Magnuson. “So when they guess how long it takes on average for a company to IPO, they grossly underestimate it.” In Braze's case, it took a full decade from founding to IPO.

But a dose of stubborn optimism certainly helped fend off doubts in that early waiting period. Did Magnuson see all of this coming? Not no. “I’d often get this question as we reached these milestones, like opening a new office or ringing the bell at Nasdaq or speaking at an in-person all hands to over 1,000 employees,” he says. “I've always answered that I never thought we wouldn't. I didn't like to explicitly think through the details of what scaling would mean, but I never assumed we wouldn't succeed and continue to grow.”