This is the fifth installment in our series on product-market fit, spearheaded by First Round partner Todd Jackson (former VP of Product at Dropbox, Product Director at Twitter, co-founder of Cover, and PM at Google and Facebook). Jackson shares more about what inspired the series in his opening note here. And be sure to catch up on the first four installments of our Paths to Product-Market series with Airtable co-founder Andrew Ofstad, Maven founder Kate Ryder, Retool founder David Hsu and X1 Card’s Deepak Rao.

In startup circles, there’s (rightfully) plenty of focus in the early days on picking the right problem space to tackle. Choose a problem too narrow and you run the risk of building a niche solution without a large enough market. Or choose a problem too broad and you’ll likely spread your small team too thin as you attempt to boil the ocean.

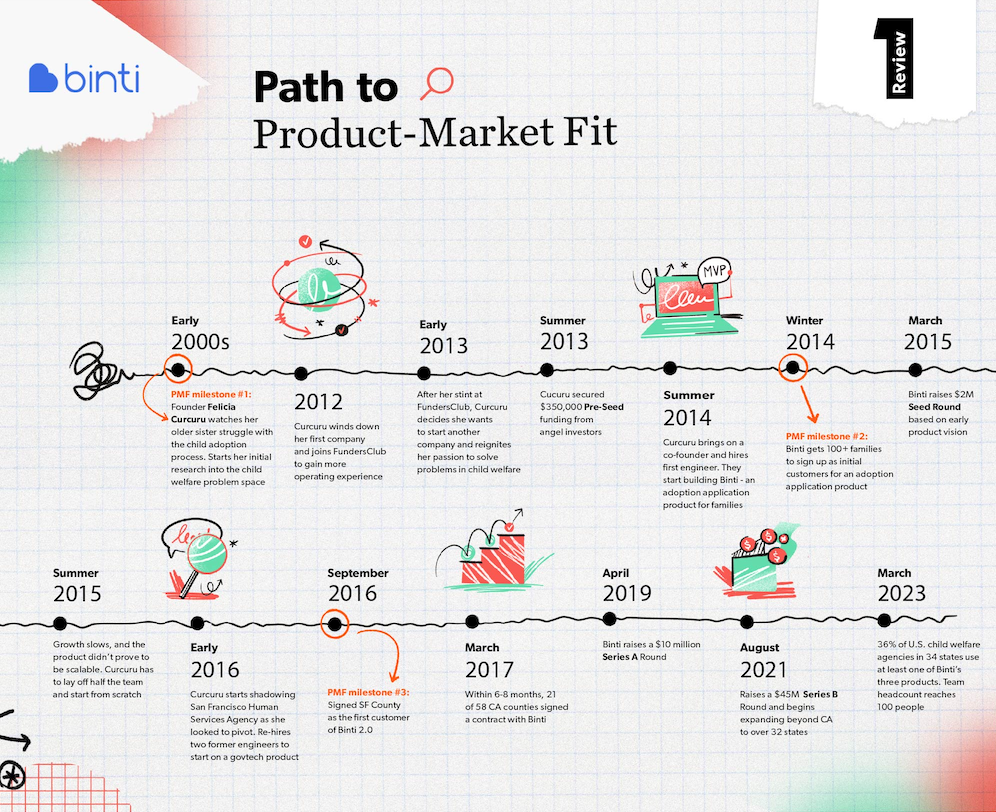

But on the path to product-market fit, choosing the right problem is just one stepping stone. After choosing a problem to solve, there are likely all sorts of different permutations of what you could build — the key, as Felicia Curcuru found, is to experiment with problem-solution fit.

Curcuru is the CEO and co-founder of Binti — a technology company building enterprise software for state and county child welfare agencies to empower more children to have permanent families. After watching her older sister navigate the complexities and frustrations of adopting a child, Curcuru became fixated on creating a solution to the sprawling issues with child welfare.

Though Curcuru’s mission to help more children have permanent families never wavered, getting to the right solution to fit this problem was a long and winding road. Curcuru had to pivot on her target audience, dismantle working products, and start from scratch to find stickier product-market fit.

Binti’s largest product offering today is child welfare software for child welfare agencies at the state and local levels. It enables these government agencies to streamline the foster/adoption application process for families that are applying and helps the social workers on these cases stay organized and save time in the midst of overwhelming caseloads and thousands of children in need. Binti also has newer products that help social workers match families with children, find relatives who can take in children, as well as support families who are struggling to get services to stay together or reunify.

Currently, Binti team is over 100 people and the product is used by more than 400 agencies across 34 states, serving over 36% of the country and over 100,000 children nationally. But the secret to Binti’s success wasn’t market magic or pure luck. Curcuru’s most powerful strategy was taking the time to immerse herself in the problem space and not being too precious about her early set of ideas.

Curcuru tells the story of how she pivoted hard to achieve nearly ubiquitous product adoption for child welfare agencies in California, and how sitting side-by-side with social workers became the most powerful accelerator in launching her startup.

EXPLORING IDEAS

Curcuru was still a teenager in high school when her sister adopted two children. She saw how confusing and stressful the process was and had heard there was a shortage of families. This didn’t make sense and she decided to research more.

As she dug in, she learned about deeply disheartening statistics. She discovered that roughly 400,000 children in the U.S. are in the child welfare system and millions of children around the world are in orphanages. Over the course of their lives, 50% of foster youth in the U.S. will be homeless at some point and 50% will have experience with the criminal justice system by the time they are 17.

“I saw all of this and thought, this doesn't make sense,” she says. “If there's such a need for more foster and adoptive families, why is it so hard to become one?”

This was the kernel that Curcuru tucked away as she started her professional career. She studied economics at Wharton and went on to do a three-year stint at McKinsey. She started her first foray into entrepreneurship by launching a gifting startup.

“It didn't go well, and I made all the classic mistakes,” Curcuru says. “I considered pivoting within the gifting space now that I'd learned some hard lessons, but I also realized I didn’t actually care that much about the problem space.”

After winding down her gifting startup, Curcuru went to work for FundersClub — an online venture capital marketplace — to get a deeper perspective of how a tech company operates. With more operating experience under her belt, she felt ready to try her hand at becoming a founder once again.

As Curcuru started tinkering with the idea of starting another company, all of the statistics from her earlier research into child welfare, and her sister’s experience trying to adopt, quickly came flooding back to her.

Make a list of problems you care most about in the world. Starting a company is hard and you’ll be much better at sticking through the hard periods if it’s something you are passionate about.

She had landed on her next startup idea, a product for helping families with the adoption process. Early on, Curcuru had a knack for leveraging key relationships in her life. “Fortunately, with my gifting startup, I hadn't raised any money and instead used a bunch of my life savings from McKinsey,” Curcuru says. “This time around, I knew I wanted to raise funding and so the first thing I did was raise a $350,000 pre-seed from angels that I had gotten connected with from FundersClub. During that time, I talked to a lot of families about their adoption experience to understand the challenges, hired a friend as an engineering consultant, built the first version of the software, and launched with our first few families.”

Here’s how she describes the first iteration of the product: “Originally, what we built was like TurboTax to be a foster adoptive family. Families could apply online on their phones, fill out documents, upload copies of their ID and collaborate with everyone in the process that needs to complete paperwork,” she says.

During those eight months, Curcuru did the co-founder dating process with several people, but didn’t put building on hold while she looked for the right fit. “I got the advice, ‘Make progress and people will be drawn to what you are doing.’ After eight months, one of my best friends decided to quit Google to join as my co-founder.”

Abiding by the mantra to do the things that don’t scale in the early days, Curcuru worked with families one by one, providing bespoke customer support as they filled out each adoption form. She had already hand-held 100 families through the adoption application process by the time she raised her First Round-led seed round of $2 million in 2015.

Pivot hard and pivot early

“At the time I thought things were going well,” Curcuru says. “But pretty shortly after raising our seed round, the growth plateaued. We didn’t have any recurring customers because people tend to adopt once — maybe twice. I think we had roughly 20 families per month and it was incredibly hard to get to double that growth to 40. Equally importantly, we realized that government agencies controlled the whole process, so we were sort of holding people’s hands through a process we didn’t really control, and therefore, we weren’t helping very much.”

“I wanted to make the process easier for families to adopt, so I originally talked to them about their experience, but I hadn’t talked to agencies that were on the other side of the process. While we were helping families navigate the adoption process, ultimately the product we were building wasn’t solving any problems for the agency side,” she says.

This was a lightbulb moment for Curcuru in Binti’s growth journey, but it didn’t come without a price. After realizing that a consumer-based product wasn’t the path with the greenest pastures, Curcuru had to assess the resources she had left and regroup to find a way forward. This meant letting three of her six team members go.

“I then went into an even harder period of uncertainty,” Curcuru recalls. “I became interested in building Binti because I wanted to solve this incredibly complex problem of children not having a family, which is foundational to having a fair chance at life. It was something I cared about deeply and I didn’t want to abandon this problem, but I was frustrated because I wasn’t solving it well.”

Co-founders shouldn’t shy away from pivots even if they bring up hard conversations — Curcuru suggests leaning into them instead. A pivot can be a natural point in a startup’s life to check back in with your entire team — more specifically your co-founder — to make sure you are on the same page with where you want the company to go moving forward.

“Every day I was brainstorming and coming up with a different idea for Binti,” Curcuru says. “I started getting excited about exploring a product for government agencies, but my co-founder wasn’t as passionate about working with government. She asked me to go on a walk one day and told me she was going to step away from the company.”

“It was hard on both of us because she is one of my best friends and I wanted to work with her for the long term. We both felt sad about it, but we just weren’t aligned on where we wanted to take the company. She’s still a close friend now, but that was a very hard moment both personally and professionally for me.”

BUILDING THE EARLY PRODUCT

Back to a team of one, Curcuru buckled down and went back to the drawing board. “I still had a million left from my seed round and lowered my salary to just $30k,” Curcuru says. She jokes that this gave her about 30 years to figure out how to make her startup work. “I wanted to make Binti un-killable.”

To find her footing in the world of social work, Curcuru knew she needed to consult the experts. Around this same time, the San Francisco Mayor’s Office for Civic Innovation launched the Startup in Residence (STIR) program. The initiative matched tech workers with government employees to better understand what issues the city faced, hoping to eventually lead to new tech solutions that would spur government efficiency.

Curcuru pounced on the opportunity. She reached out to someone in San Francisco county’s child welfare team who informed her that they were struggling with a shortage of foster families and she was invited to shadow a group of social workers in San Francisco’s Human Services Agency for four months. Her experience in these halls turned out to be a treasure trove of institutional knowledge and relationship-building that became the foundation for the next version of Binti.

“I was side-by-side with social workers who do the licensing for families so they can become foster parents. A typical day for them might start with a visit to a potential foster family to inspect the home for safety and fill out a checklist for everything they see during a visit. But they ended the day at their desk where they had this spreadsheet that they called the ‘master grid.’ It was 70 columns and 1,000 rows shared across a couple of dozen social workers that just tracked every step in the licensing process for a family.”

For the first time, Curcuru got to peek behind the curtain into the technical stumbling blocks that made the adoption and fostering process less efficient. “The spreadsheet wasn’t up to date and was so overwhelming for social workers to try to navigate. Instead, they resorted to sticky notes posted everywhere and all sorts of manual workarounds,” she says.

It started to make sense why families had such a difficult experience with the fostering and adoption process and why it was so slow. Social workers got into this work because they want to help children and families. They were trying hard but they didn’t have the tools to do their jobs effectively.

Curcuru wasted no time. She called up two former engineers from the first iteration of Binti and hired them as paid consultants for Binti 2.0. The small team started to build out a tool for the social workers she was shadowing, getting feedback from them in real-time.

“We replaced their massive spreadsheet with a dashboard where social workers can log in and see in real-time what parts of the application the families have completed, what's missing and the in-flight background checks,” Curcuru says.

The goal was to build a product that would get more foster and adoptive families approved in a shorter amount of time. “Social workers can track when potential foster families show up to trainings and then they can complete the safety inspection of the home on their phone — all within the same system.”

After a long period of tweaking, adjusting and experimenting, Binti was reborn. “At the end of those four months, San Francisco agreed to be our first government customer. At that point, I also asked one of the two engineers who had rejoined to be my new co-founder and CTO,” Curcuru says.

Advice for user research: Common mistakes to avoid

Simply signing up to spend time with potential customers isn’t enough alone to generate viable user research. It’s about maximizing that time to gain as many valuable insights as you can through thoughtful questions. For founders curious about doing their own customer development research and diving deeper into an unfamiliar field, Curcuru outlines the best tactics she learned the hard way:

- Mistake #1: Asking leading questions: “Try not to come into your interviews with hypotheses. I had a strong hypothesis of what I wanted to build and I would ask leading questions like ‘Does this product sound like something you would use?’ to confirm my assumptions,” Curcuru says. Instead, lean on open-ended questions like “If you had a really successful year next year, what would that mean for you?” and “What are the barriers to achieving those goals you mentioned” and “What are the most frustrating and time-consuming parts of your role?”

- Mistake #2: Being too abstract: “You have to roll up your sleeves and get into the nitty-gritty details,” Cucuru says. “I think often founders (including me in the first part of Binti) stay too high level in their understanding of a process. Have your customers walk you through what their workflow is and learn it to the degree that you develop deep empathy for their role and experience. You have to understand it at that level to challenge the way things are done and propose new ways of doing them.”

We want customers to walk us through their workflow end-to-end and dig into every little detail. What’s challenging them? What works well? What are the barriers?

LAUNCHING

While time-consuming to spend months shadowing social workers when she could have been heads-down building, Curcuru’s effort was well worth it — within eight months of building the new product, Binti had contracts with 21 out of 58 California counties.

But the steady drip of customer feedback didn’t stop after launching the product — Curcuru continued to check in with each new feature the team added.

“In general, our customers are open to giving feedback because social work tends to be an overlooked field for software and not a lot of entrepreneurs have spent time listening to them and asking them, ‘how can we make things better for you?’” Curcuru says.

For founders solving in non-technical problem spaces, seeking out those who have a knack for technology will prove to be exceptionally helpful as potential design partners or brand evangelists, Curcuru says.

“Out of the 14 social workers and two supervisors in the office I shadowed, one of them was very interested in technology,” Curcuru says. “She was tech-savvy, used lots of software in her personal life and was frustrated that there were no tools that would make her workflow easier. She gave a lot of good feedback and now actually works at Binti.”

Make sure your product will work for more than just one customer

Look for opportunities to create a chorus of different voices from users, rather than honing in on just one. By broadening the scope of feedback received, founders can prevent the common conundrum of building something that is too specialized for one group’s needs.

“I wanted to make sure I was not building a product just for San Francisco,” Felicia said. “So during those four months shadowing San Francisco County, I also spent time with other agencies around the country. Most government software is custom built because things vary state by state, and even county by county — but I did not want to build custom software.”

For example, Curcuru attended national conferences for child welfare and tried to get face time with folks. “I just went up to random people. They’d tell me that they were a social worker in Florida and I’d say ‘Awesome. Can we sit down and map out your end-to-end documentation process?’”

Curcuru had these same conversations for eight different states, giving her a feel for where there might be overlap or similar challenges. “I became an expert on what is the same and what is different across the country and we make those things configurable — that is part of our secret sauce,” she says.

Going to market

Curcuru’s initial go-to-market strategy was to harness her customer’s credibility and leverage the relationships she built. With San Francisco on board as an anchor first customer, and a Rolodex full of social workers with glowing reviews about Binti, Curcuru was able to source nearly all of her early customers through word of mouth. Sales calls started to go off without a hitch.

“It was clear very quickly that there was strong demand for what we had built. Customers got very excited about the demos and quickly would ask about the cost and how long it would take to launch.” Curcuru says. “That was the first time I started to understand what it felt like to have customer pull. The first couple of years when we were trying to sell directly to adoptive families, we did not have pull,” Curcuru says.

How do you know when you’re close to product-market fit? If you don't have it, you feel like you’re pushing a boulder uphill and if you do have it, you're chasing the boulder downhill.

“I really felt that difference,” she says. “I felt like the first couple years I was shoving the idea down people's throats and they didn't care. But the second time around, I would talk to social workers in San Francisco and ask ‘Hey, do you know any neighboring counties who would be interested in this?’ And they would say ‘Yes, I know people in Marin and Alameda and San Mateo, and I'll put you in touch.’”

Landing on the right price

Curcuru’s next challenge was one that a small set of lucky founders are fortunate to find themselves in. Demand for her product was high, so what should she charge?

For guidance, she leaned on advice from a senior pricing leader at Salesforce for their framework on early product sales. His advice:

Calculate with your customer the value you’re providing, and then charge 10% to 20% of it to start.

To quantify that value, Curcuru sat down with folks in the San Francisco child welfare office and crunched all the numbers. “Binti ultimately provided value in a number of ways that could be quantified as cost savings to the county, in addition to providing impact to children. We calculated how exactly Binti was saving money and what the dollar value of that time saved was. After coming up with a number, I asked ‘How about if we charge 10% of that number?’ That was pretty aligned with them in terms of what they were expecting. We then used that as a formula for other customers.”

Once the pricing was set, Curcuru knew it was time to build out the team — although she was much more cautious this time around. “One mistake I made in the first iteration of Binti was just hiring too quickly,” she says. In fact, once she pivoted and started building Binti 2.0, the company operated as just Curcuru and her co-founder until they hit $500k in ARR.

Before you have product-market fit, it can be a distraction to recruit, hire, onboard and manage people when instead you should be hyper-focused on finding product-market fit. Plus, when things aren't working, you have to manage not just your own morale but everyone else’s morale.

THE PATH FORWARD

Curcuru’s case goes to show that even if founders think they know the problem, they can always dig even deeper and find different angles. Especially for mission-driven startups like Binti, there’s usually a reason that progress in the problem area hasn’t been made. Taking the time to understand the deep processes and complexities that her potential customers faced every day became the ultimate accelerator for Curcuru — and while their early products now have strong product-market fit, Curcuru and team continue to use these same immersive user research methods as they build and launch new products.

The road to product-market fit can take years, and even once it’s achieved, it’s still a long trip ahead to scaling and operating a company. Curcuru’s journey was not without its own set of unique challenges. She faced personal health scares, watched years-long friendships drift apart and had to make do with extremely limited resources. Her advice to other founders is to carve out space to take care of themselves.“Take at least one full day off a week. Ideally, you can get to two — although I'm still not really at two. But I definitely take one day off a week, and I think that's really important for not speeding towards burnout.”

Startups are really hard and you're going to hit low points. You need to really care deeply about the problem you’re solving to be able to persist through it.