Qasar Younis believes company building is a craft — one that he’s worked hard to master since he was a kid.

Younis grew up in a working class family in a Detroit suburb shaped by the auto industry. He started working at McDonald’s at 14 and juggled multiple jobs all the way through college, studying engineering and working part-time on the factory floor at the General Motors Institute.

But when he watched his dad, an auto worker who’d struggled as jobs began to move to China, start his own business, he dreamed of one day doing the same. “He started his own small business, which he still runs today. That’s been hugely informative to me. I saw him get his dignity that way. He really became a master of his own destiny,” he says.

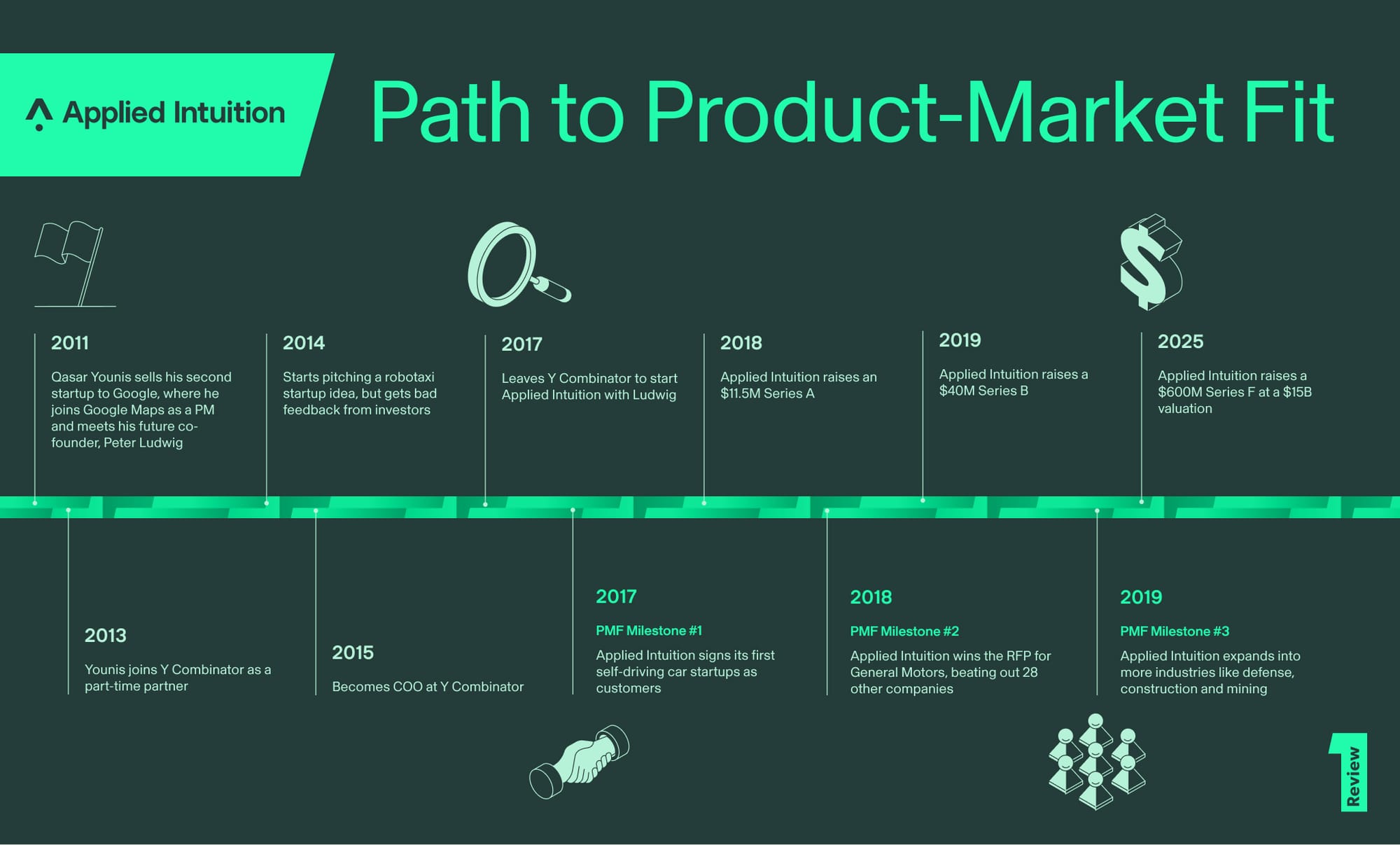

That set Younis on a mission to collect experiences that might one day increase the odds of building his own successful company: engineering jobs at General Motors and Bosch, business school, a stint at a holding company to “learn finance.” He founded two startups — the first, a crowdfunding app, never gained much traction. The second, a consumer-to-business messaging platform, sold to Google, where Younis went on to work as a Group PM for Google Maps. After that, he spent several years at Y Combinator as COO. “I fundamentally see myself as a founder, and as an engineer, a lot more than I see myself as an investor or an employee,” he says. “So that was always in the back of my mind: I knew I needed to get broad experience across all kinds of functions in a business, technical and non-technical.”

In 2017, Younis was ready to start a company again. He teamed up with Peter Ludwig, a PM he’d worked with at Google and a fellow Michiganite. Their shared experiences, from growing up in Motor City to building sensors for a Google Street View car, had materialized in a startup idea: software for automakers developing self-driving cars.

Today, that company, Applied Intuition, is worth $15B, counts 18 of the top 20 global automakers as customers (including General Motors), and is leading the physical AI revolution — deploying intelligence in machines from submersibles to cars to fighter jets. In this exclusive interview, Younis lays out both the personal and business moves he’s made to build a company only he could start. Let’s dive in.

A founder’s education: From venture capital to Andy Warhol’s autobiography

Younis inadvertently landed his job as an investor by trying to start his third company. While still at Google, he and Ludwig originally had an idea to work on a robotaxi startup together, given their shared familiarity with the auto industry and hardware experience at Google. Younis pitched a few funds, including Y Combinator.

But Paul Graham told him he wasn’t sure if it was a good idea, and offered him a job at Y Combinator instead. Younis didn’t have enough conviction in the robotaxi idea to turn down the job — so he joined Y Combinator, and Ludwig stayed on at Google.

Going into YC, Younis fully expected to start a company again. So he spent his time there obsessively studying the ingredients of a successful startup. “At YC, whenever I assessed companies, I’d always think about how I might do it instead — what’s right about this? What’s wrong about this?” he says. “A place like YC is fantastic for that, especially if you’ve been a founder before and you can start pattern matching.”

On paper, Younis believed he’d gathered all the right experiences to lead another successful company: engineering, finance, business school, product management, investing — even starting two companies. But in his view, training to become a well-rounded entrepreneur doesn’t begin and end with professional endeavors. He’s found exploring his personal curiosities to be just as important in shaping another important quality in founders: curiosity.

“I’ve always read a lot. Not airport books about quick growth hacks. I believe you can read Roman history or Andy Warhol’s autobiography and learn how to build a company,” he says. “Knowing what good art is makes you a better founder.” Younis doesn’t identify single things he’s read from these books that shape how he’s building Applied Intuition, but the residual knowledge sits in his brain for pattern-matching later.

If you’re curious about Younis' reading list, you can find all his favorites here, but his taste in books can be boiled down to this: old, and unrelated to tech and startups. “The closest thing to a business book I read would be something like The History of the Standard Oil Company, but it was written in 1905. I tend to read books that are more than 25 years old, because the trends and short-term noise have been filtered out,” he says.

Whether it’s great music, great art or great ideas, founders should consume media that’s well outside of their domain. If you consume low-quality content, you’re going to get low-quality ideas.

Founding order of operations: Team, market, idea

In 2017, Younis left Y Combinator and teamed back up with Ludwig to begin exploring markets and ideas to pursue.

Looking back, Younis says this founding formula worked well for Applied Intuition: Choose a co-founder, then a market and then an idea. In that order.

1: Find a co-founder who’s seen your ups and downs (and vice versa).

“I really believe finding a co-founder has to come first,” says Younis. “If you have an idea then find a co-founder, they’re really just a glorified employee. They weren’t there for the birthing of the idea, so the idea probably isn’t as tied to their skills.”

But don’t go founder speed-dating. “You can’t compress the co-founder search into a one- to two-month period. You need to see this person evolve over many years.”That was the case with his friendship with Ludwig, which began when they worked together at Google. Younis says their co-founder chemistry was evident from the start — even outside of work. “Peter’s and my parents live a quarter mile from each other in Michigan. So we have some obvious shared values,” he says. “If you ask someone who’s worked at Applied Intuition they’ll often say that he and I are perfectly balanced. If I just ran the company, or just he ran it, it wouldn’t work.”

When you start a company with someone, you’re climbing up the side of a mountain and hooking yourself to that person. If they fall off that mountain, you do, too.

2: Choose a market that’s familiar and fast-growing.

Once Younis and Ludwig were ready to take the founder leap together, their next order of business was picking a market.

That starts with identifying a market in which you both have experience. “After finding a good co-founder, market timing is everything,” he says. “It’s the beginning, middle and end of your company. So between you and your co-founder, look at which markets overlap in the Venn diagram of your experiences.”Younis’ second requirement for a market was one that was on the cusp of a boom. “If you're an aspiring founder, you have to go to a market that’s exploding in growth. Generally speaking, if there’s already a huge competitor in the market, you’re not going to fare as well,” he says. “If you go to the dentist CRM market that already has seven players, for example, it doesn't matter if you can make a way better product. It's tough to penetrate that market.”

Younis and Ludwig narrowed their list down to a few different soon-to-be-hot markets — but realized they were neglecting their first piece of criteria. “At the time, in 2017, the growing markets were crypto, AR/VR and autonomy,” he says. “We actually built a few demos in those first two markets. But then we realized, ‘What are we doing? We don’t know shit about voice. The thing we really know is software, and autonomy is a growing market, so let’s learn about that.’”

They were confident that the timing was right to get in early before any big players emerged. “We figured, if we can survive long enough until autonomy technology will converge, then we’ll not only have momentum, but we’ll already be there when the market turns,” he says.

3: Zero in on a problem in that market.

After spending some time exploring the market, they noticed the striking lack of software tools available to build and test autonomous systems within vehicles. So they came up with a software idea: engineering tools for automakers working to develop their own autonomy programs.

Instead of predicting the future of the autonomy market, they chose to cast a wide net. “We wanted to build a product that could be used by anyone, because we weren’t sure where the ecosystem was headed, or which self-driving car would win,” says Younis. “Is it going to be a self-driving truck? A college shuttle? Tesla? Waymo? We didn’t know, so we figured we’d build a horizontal product to fuel the entire ecosystem, because we didn’t know when autonomy would truly take off.”

Younis and Ludwig pursued the engineering tooling for autonomy idea and went out to raise a seed round. On the other side of his stint as an investor, Younis had learned how to parse through feedback on startup ideas. While his original robotaxi idea was met with skepticism, investors had a strong appetite for Applied Intuition, which he took as a positive signal.

“If I ask an accountant at a tool and dye shop in the suburbs of Tulsa whether Applied Intuition is a good idea, that feedback isn’t important. But if you ask an investor, and they tell you no, you should think about that. A lot of founders just don’t,” says Younis. “I say listen to the naysayers. Founders have a really hard time being objective about their ideas. Their instincts tell them, ‘No one’s going to get your thing,’ so they just keep at it. But sometimes you actually shouldn't keep at it.”

A founder isn’t made when they start a company. A founder is made when they get feedback about the product, the market, or themselves, and interpret it correctly.

Building multi-product from day one

Younis and Ludwig recruited a handful of engineers and got started building the product — all together, out of a house in Mountain View.

“We only left when we got to a size where we couldn’t all work from the living room. A neighbor even asked me one day, ‘Are you guys running a company in there?’ And I just said, ‘Ah, it’s just some friends working from home.’ We got a notice on our door the next day,” Younis laughs.

Younis made a bet to build out the second product in quick succession, within a year of starting the company. The first product was a planning simulator, followed by a perception simulator, and then a data logger. “We went multi-product quickly out of a practical reason: The first product we were building covered so much space that the customers were still paying for a much richer product. We had built a mass of a product which became our second product, so we could actually charge for it as a separate product,” he says.

In hindsight, Younis says going multi-product as a young company was the right call. “As a founder, you have to make a decision about whether you’re going to be a single-product company or a multi-product company. From the early days we decided to be a multi-product company,” he says. “It's really hard to find product-market fit again and again and again. It's really hard to manage dozens of products and make sure they're all the right products and the market needs them, and you're not just holding onto them because you started them four years ago. We built the muscle to take feedback and build a product around that feedback.”

Go-to-market: Start small to perfect the product, then go big

Younis made a calculated GTM bet: start in Silicon Valley as a stepping stone to global automakers, and eventually other industries.

He knew the Boschs and General Motors of the world were worthy big fishes. Having worked at both companies, Younis knew their wallets were deep (Bosch, for reference, pulls in north of $65 billion in revenue per year, just in the automotive category). Second, he understood that one big account could contain several customers — a company like Stellantis has dozens of sub-brands with different teams working on self-driving.

But he knew there was no point going after the huge automakers while Applied Intuition was still ironing out their first suite of products. So Younis chose to start by selling to companies that looked a lot more like Applied Intuition.

“We knew these huge car companies would be hesitant to buy stuff from a young company. They’re working on five- to seven-year autonomy programs, so that doesn’t make sense,” he says. “Our early insight was to sell to Bay Area companies working in autonomy because the size of those companies were similar to ours, and we could use that as a springboard into the traditional original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), which was our endgame. That was our original wedge to get the right to sell. Because both the startup and the large automaker are working on the same problem: autonomy.”

The GTM test, in Younis’ view, was simple: Applied Intuition’s products had to be exceptional. “We’re a company that can only be judged on the quality of our products. We’re a hard tech, software-only enterprise company. So the only analysis is whether this product does what we promise it can,” he says.

One of Applied Intuition’s first customers was Voyage, a self-driving car startup that was later acquired by Cruise. Younis says working with these startups gave the team a feedback loop to build a more sophisticated product and gain deeper insights about autonomy. “Our first few customers gave us not only dollars, but the feedback we needed to build our next-generation product, which we wanted to be good enough to pitch to General Motors.”

The strategy panned out: In 2018, Applied Intuition did a formal RFP alongside 28 other companies to compete for General Motors’ autonomy tooling business. They won — which gave them the confidence to start going after other million-dollar accounts. “We won against the big companies like Nvidia and Ansys,” says Younis. “We were still a small company at the time. We just had the best product.”

After signing the first few automaker heavyweights, Applied Intuition expanded into other industries, starting with defense, and later signing construction, mining and trucking customers.

Scaling up

A clear sign of product-market fit in retrospect, says Younis, is that Applied Intuition has always kept all its money in the bank. “We've preserved all the capital we've ever raised in the company's history, which is evidence that the company is an efficient, cash-generating entity — the products we build are wanted by the market and the market's willingness to pay us more than it costs to build the products,” he says.

Ultimately, Younis says the idea for Applied Intuition was validated by the market quite quickly — within the first several years — confirming the pattern he’d observed as an investor at Y Combinator. “The good companies were good pretty quickly and then were good for 10 years, and then they went public,” he says. “With Applied Intuition, we got traction from fairly early on in the company. We didn’t have to wonder whether it was going to work.”

As Applied Intuition went on to grow into a multi-billion dollar, thousand-person company over the following years, Younis says these are three of his own personal values that have kept the company on its breakout path.

Be cost-conscious

Younis has kept a tight P&L sheet since the early days. “We’ve tried to keep our focus on making this a viable company. Being cost-conscious is one of our core values. And it’s worked out,” he says.

Salary is one area of particular discipline at Applied Intuition, which Younis says diverges from the staggering total compensation packages at well-funded startups nowadays. “You can look at Levels.fyi — you often get paid more to go to a startup than to Google or Facebook, and those companies generate billions in cash flow every month,” he says. “So you wonder why all these companies raise money and are never profitable: It's because they actually have a really bad compensation strategy.”

To buck this trend, Younis stuck with the old-school model: Reduce salaries and increase equity packages to start, and both will increase as the value of the company goes up. “The vast majority of our employees are now at the 99th percentile of compensation, but not because of their first offer,” he says. “They’re there because the stock price grew. That’s the right way to do it. You get stock while it’s cheap, you contribute to the company’s success, and you get rich over time.”

You don’t need to win by a wide margin

Younis doesn’t subscribe to the “don’t worry about your competition” philosophy. “Maybe you didn’t have to worry about the competition in 2010, when it was exotic to build a company, but now we’re in the industrial age of venture capital,” he says. “There are more startups, more dollars, more competition.”

You don’t have to win by a lot to win all the same. “In this ecosystem, if you can stay just a little ahead, and if you can keep that lead, you can become the number one player,” he says.

He takes Applied Intuition’s internal deliberation on which AI coding tool to purchase as an example. “If you just look at the universe of coding tools, we did a whole evaluation with hundreds of engineers to pick a tool to roll out internally. We ultimately chose Cursor, and I asked, ‘Is it really the best product or is it incrementally better?’ And our head of infra said, ‘Just incrementally better, but better enough for us to pick it.’ That compounds — that’s how Cursor became a juggernaut.”

In Silicon Valley, if you can pull just a little bit ahead, and you can keep it, you can become the number one player.

Hard work compounds

Younis’ teenage obsession with hard work has never wavered. “I’ve worked seven days a week for as long as I can remember,” he says. “Whether it’s having multiple jobs or one job where you work all the time.”

Looking back in the rearview mirror, he sees how that extra work has compounded over time, from the initial team’s Applied Intuition hacker house to the early days of his engineering career.

“Forget the seven-day work week. Just work 10 extra hours per week, and that compounds in significant ways. On an annual basis, that becomes three extra months.”