Last year, Jiaona Zhang left Webflow to join Linktree as the social tool’s new Chief Product Officer. Within two weeks of starting her new gig, annual planning kicked off — and she was somehow in charge of it.

While her stacked resume from Dropbox, Airbnb, WeWork, and Webflow provided valuable experience, it also came with its fair share of annual planning scar tissue. There were plans that were chucked aside one quarter into the new year. Countless cycles of back and forth. A 10-page strategy doc with detailed dependency mappings — that quickly became obsolete when planned headcount was slashed in half.

Of course, she’s not alone in this experience. Planning has long been seen as one of the most painful organizational rituals. And there’s a case to be made that there’s only more turbulence ahead. Every new LLM rollout now risks upending your plans, whether it’s scrambling your product roadmap, changing your headcount calculus or ballooning your budget for new tooling. “The world is increasingly unpredictable, so the question now looms larger: What role does annual planning even serve?” says Zhang.

After much reflection on the root cause of the issue, here’s her diagnosis: “The commonly held practice of ‘I’ll just do what I did at my last startup’ or ‘Let's figure out what X company did and copy it’ sets you up for a lot of heartache. You shouldn’t copy-paste without a lot of introspection,” she says.

She points to her own experience with the W framework, a planning approach from her time at Airbnb. (If you’re not familiar, Lenny Rachitsky walked us through this process in a great guide right here on The Review several years ago. We’d recommend giving it a read if you missed it.)

The framework's core principle — balancing top-down direction with bottom-up proposals — proved invaluable for Zhang. “It catches a lot of the failure modes that can often happen, whether it’s leadership prescribing a path that is ultimately impossible, or teams running in different directions because there’s no overarching strategy,” she says.

Even so, Zhang found that it didn’t all translate seamlessly to her role at Webflow. "We ran into a few nuances that I hadn’t encountered at Airbnb. Webflow was building out an enterprise business, which required us to actually run sales planning concurrently. They needed to go through their own mini W process since they needed headcount constraints upfront, but then locking their plan ultimately depended on how much product could deliver,” she says. “It’s not that the approach didn’t work, it’s that we needed to tailor it more to our company.”

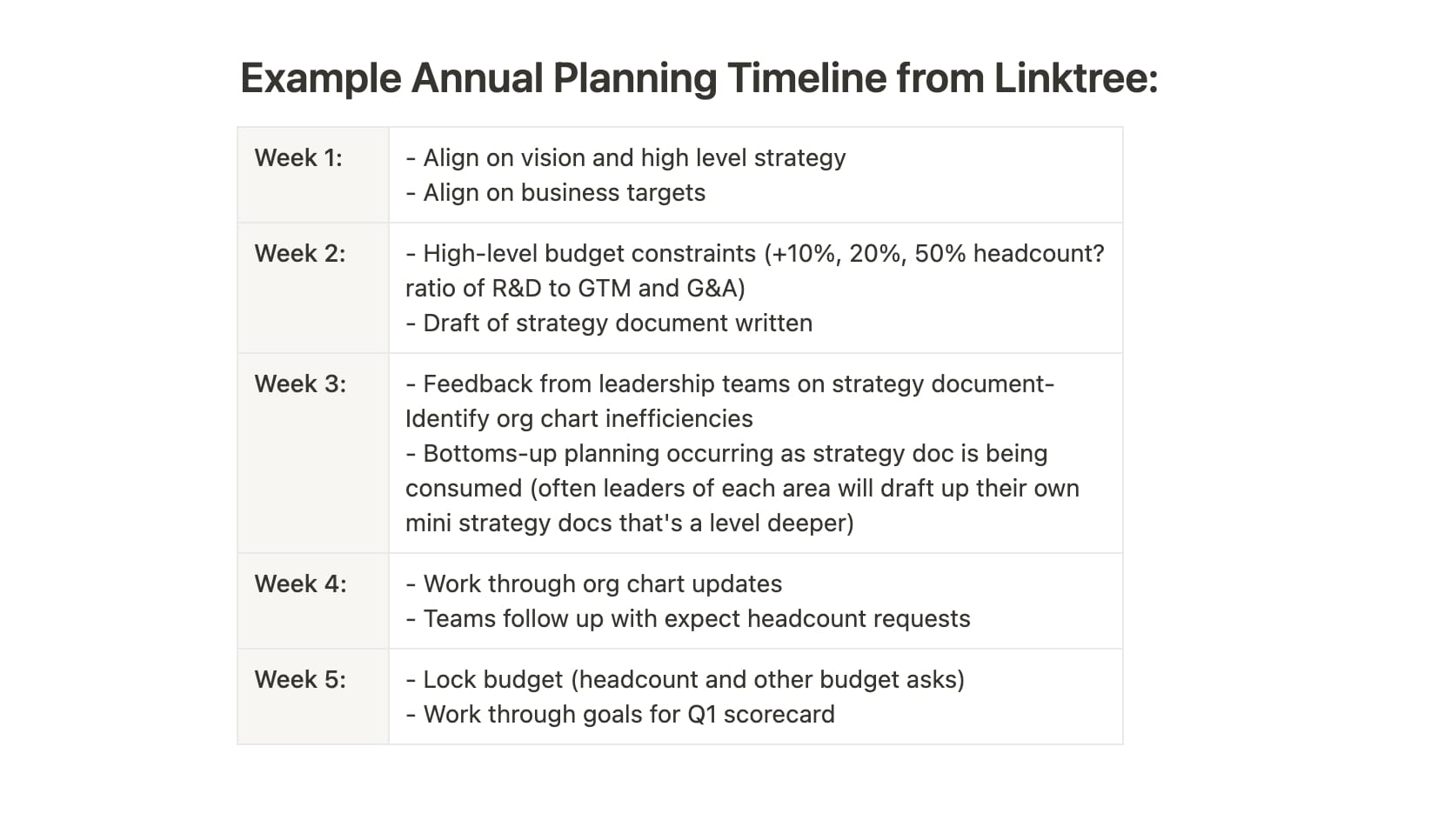

This experience shaped Zhang’s first annual planning at-bat when she joined Linktree. “Speed was a priority. It’s something of a personal point of pride that we were able to start and wrap annual planning for 2024 in just five weeks, despite the fact that I was still so fresh,” she says.

Every company’s planning process needs to be optimized for what their problems are, the market they’re in, and the team they have to execute the planning.

– Jiaona Zhang (“JZ”), CPO at Linktree

Inspired by these experiences, Zhang has been quietly working these past few months to pull together a resource that helps more startups do just that.

Rather than proposing a one-size-fits-all framework, she advocates for anchoring on a set of principles and drawing inspiration from a wider aperture of sources — but applying a YMMV lens toward how your startup differs by stage, business model, customer, and company culture. That’s the recipe, in her experience, for crafting a process that helps you see around corners and common traps as you scale, while staying malleable enough to suit your specific needs.

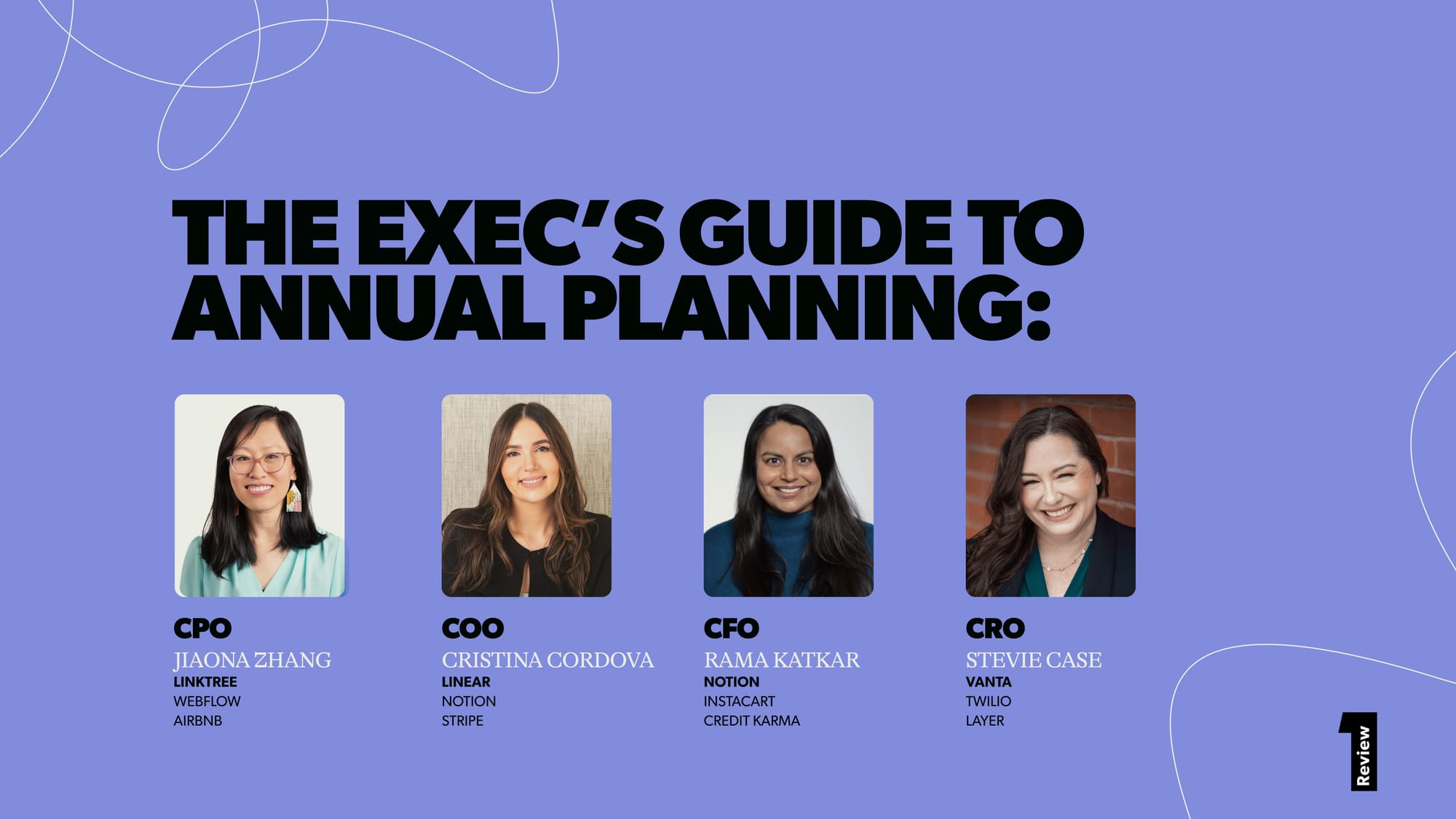

To help you shoulder that work, Zhang tapped her network to find sharp execs across different companies and organizational functions, bringing together an annual planning brain trust of sorts. Their collective experience shaping annual planning at some of Silicon Valley’s buzziest companies cuts across industries and business models, from fintech and consumer, to PLG and traditional enterprise sales.

In addition to Zhang, you’ll hear from:

- Cristina Cordova, COO at Linear, formerly Head of Platform & Partnerships at Notion and Business Lead at Stripe (where she joined as the 28th hire).

- Stevie Case, CRO at Vanta, formerly VP of Enterprise and Mid-Market Sales at Twilio

- Rama Katkar, CFO at Notion, formerly VP of Finance at Instacart and SVP of Corporate Development & Strategic Finance at Credit Karma

They’ve also spanned various stages of growth, from pre-PMF to IPO prep, so they’ll share practices that can stand up to a scale-up, while also offering more lightweight tips for earlier stages. (So you have a better sense of their current roles: Linear is a Series B startup, with a ~60-person team, Linktree is Series B and ~150 people, Vanta is a Series C ~600-person company, and Notion is also Series C, with ~800-people.)

Sometimes their advice might seem slightly at odds with each other, with some focusing more on brand and storytelling, while others are more math-driven, with down-to-the-penny targets. That’s by design. The variety of approaches here will help you find your fit.

No matter if you’re about to kick off annual planning or you’re already in the thick of it (and perhaps eager to course-correct while there’s still time), we’re confident you’ll find nuggets of wisdom in the lessons these leaders have collected over the years. From sharpening your strategy and forecasting, to the nuts and bolts of org design and goal-setting, this (long) read offers a unique deep dive into the different perspectives key functions bring to this process.

Whether you're an early-stage founder running your first planning cycle, a seasoned executive looking to refresh your approach, or a team leader grappling with how to account for AI's rapid advancements, our hope is to guide folks in creating an annual plan that’s rooted in vision yet grounded in reality — one that’s ambitious and bold but not in the grow-at-all-costs mold.

Let’s dive in.

1. Find the right approach for your company

Most teams stumble right off the starting blocks. “How do you orient the company on where to begin? Who sets the guardrails? How do you operate around them? I have found that to be universally difficult, regardless of stage,” says Vanta’s Stevie Case.

Plan to plan

This group has found it helpful to begin with a step backward. Just as the “measure twice, cut once” approach of a master tailor saves expensive fabric, making critical planning process decisions upfront will smooth your path.

Here’s a checklist of questions you and your team would ideally reason through at the very beginning to align on an approach. (If you’re already in the midst of a planning cycle and don’t have a clear answer on some of these questions, that could be a signal to hit pause and regroup.)

Duplicate on NotionBy working through these questions, you're not just grabbing an off-the-rack annual planning process and hoping it fits. You're creating a bespoke strategy, one that fits your company's unique shape and style.

Constrain your planning process, as well as debate

When to start and when to put pencils down is often not explicitly discussed — which is likely why annual planning processes tend to drag on. And it’s not just you — the annual planning process seems to start earlier and earlier each year.

“At a previous company, I was trying to schedule a meeting with someone and they said, ‘Sorry I can’t meet with you for a few weeks, we’ve just started annual planning for next year — but it was only July,” says Linear’s Cristina Cordova.

If I have one piece of advice it’s this: Constrain the timeline as much as you possibly can. Time spent planning is time you could have spent shipping.

– Cristina Cordova, COO at Linear

If you’re looking for places to trim, consider time boxing debate: “If I could abolish anything from the annual planning process, I’d ban extended opinion-based debate,” says Case. “There's a place for a certain amount of that at the very beginning, but if you're in the middle or later stages of planning and people are still talking about their beliefs, opinions and feelings, something has gone horribly awry.”

Here’s the timeline Zhang used at Linktree:

Tailor, don’t copy

As your planning approach starts to develop, studying other companies can be a valuable step — but beware the common trap of trying to force one size when it does not fit all.

Linear's Cordova shares how she threaded this needle back at Stripe: "Stripe was founded on first principles, but we also sought advice. When we did company planning for the first time, Patrick Collison sent me on a little mission to learn from execs at Google, Amazon and Facebook. We'd take elements we liked and blend them with a 'Stripe-y' approach."

One example was adapting Amazon's “working backwards” method of writing a press release early on. "We included 'User Ships' in each team's product plan, forcing us to outline the value we'd deliver to users each quarter. It was similar to Amazon, but applied to smaller features."

This approach fit Stripe's writing-heavy culture and business unit-like structure — but didn't carry over to Cordova's next roles. "At Notion and Linear, it's more 'What's the TL;DR?' than six-page single-spaced documents. Debates happen on Slack, things are faster. Planning is about quickly giving people the gist of what's happening and our focus. It's pared down, which is helpful for smaller companies."

CRO Stevie Case found a better fit bringing Twilio's approach to Vanta. "Twilio adopted a math-based approach when COO George Hu joined from Salesforce in 2017. He showed how a capacity-driven approach can drive predictable revenue," says Case. This suited Vanta's B2B direct sales model — but it likely won’t suit your startup if you’re building a PLG company (or even a hybrid one where you’re just starting to layer on sales). "Vanta actually doesn’t have a self-service component of any kind. Every dollar is generated by a human. Every deal has a quota-carrying salesperson, even expansion, so even NRR is capacity-driven for us. That’s why we're so structured around how we do revenue planning,” she says.

CFO Rama Katkar reflects on her experience of moving from Credit Karma and Instacart to Notion: “Across the places that I've worked, I’ve found that companies are at different operational maturities in their ability to attribute impact to different initiatives. Some have time series data and well-developed intuition. Other teams are doing things that are totally new, or they’ve only operated in a different macro environment,” she says.

She contrasts her experiences: “Instacart 4X’d during the pandemic, and I joined right after that, with this view that we had to get to total accuracy in forecasting because we were on the path to going public. But that wasn't marketing-led growth, that was fully viral growth. Looking at that business and figuring out what it was going to do the next month wasn’t easy,” she says.

“By the time we sold Credit Karma, the company was extremely operationally mature. There was a ton of predictability in that business. But in my early days there — similar to how it is at Notion now — we were still trying to understand how business activities actually impacted the financial plan,” she says. “It took us some time to figure out the usage metrics that were truly predictive, or how to look at cohorts in a way that actually drove engagement, which drove transactions, which drove revenue. It’s a new muscle,” says Katkar.

Now at Notion, Katkar is extending that organizational grace: “I can't expect 2-3% accuracy from all teams or to attribute every activity to revenue,” she says. “What I’ve found helpful is to give some teams more of a portfolio approach and say, ‘This is the number I need you to generate for the business. You tell me how you're going to do it,’ whereas some parts of the business are further along and can get more granular.”

As an executive, you have to meet teams where they are, and build more flexibility into the plan if that forecasting ability isn’t there yet. Don’t try to force it. Focus on how you can give your team the support they need to start to build that intuition and ability to predict the business.

– Rama Katkar, CFO at Notion

2. Start with the vision and strategy

Once you’ve plotted out your general approach and are ready to dive into the actual planning phase, the “what” and the “how” take center stage.

“If you just let teams go off on their own, chances are they're going to come back with ideas that are completely divergent. The whole point of the W framework is you start from the top with an aligned strategy — but what does that look like?” says Zhang. “Often the fail case is not coming up with a well-reasoned strategy that is focused.”

As you set out to nail down that strategy, it’s easy to get lost in the grand-sweeping vision or drill right into the product features to ship, but there are a few other components you’ve got to nail down, too:

- Vision (usually a narrative from the founder/CEO)

- Time horizon

- Investment areas (and equally importantly, areas you’re not investing in)

- Competition

Strategy is the sequencing of how you take a very long-term end goal and break that down into more digestible components. Done right, it gets you a really clear picture of what’s in your long-, mid- and short-term plans, where you stack up in the market, and how you’ll win.

– Jiaona Zhang (“JZ”), CPO at Linktree

Zhang shares the strategy doc template she's come to lean on over the years:

Duplicate on NotionVision: What’s the story?

“Strategy starts with articulating the story you want to tell the world. Humans are moved by stories. And to align an entire company, you need to tell a compelling and clear story. It also gives the leadership team a clear sense of where you’re headed,” says Zhang.

“Webflow’s vision is something that Vlad and I worked on for quite some time,” she says. “It started off as, ‘Be the world’s most powerful no-code development platform.’ It was big and ambitious — but it gave very little focus. We got distracted by all of the things you can do in the no-code space. So we changed it to ‘visual development platform.’ It leaned into what we were great at,” she says.

At Linktree, Zhang partnered with CEO and co-founder Alex Zaccaria on refining the vision as well. “When I joined, it was to, ‘Empower anyone to curate and grow their digital universe.’ Again, ambitious but broad,” she says. “A lot of the debate that Alex and I had was around if we’re a consumer app that’s all about getting every individual to express themselves, or if we’re somewhere where creators can grow their businesses? We ended up tweaking the vision to include the word ‘monetize.’”

These may seem like slight tweaks, but Zhang found they were really important. “Every word matters when it affects your strategy. Your job as an executive, particularly as the CPO — in my biased view, of course — is to really engage with the founder on how to refine it and make it better,” she says.

Three years vs. one year: What’s the time horizon?

The time horizon of that vision can look quite different, depending on the founder’s style. “I’ve come to really like the process of also starting with a three-year vision,” says Zhang.

“Oftentimes the CEO is so ambitious, and the space for the three-year vision is a great way for the founder to not feel constrained. It’s not too far in the future, but long enough to orient the team. As an exec, it’s key to follow that up with what you think can be achieved in one year, particularly when you’re still a smaller team.’”

If you don’t use markers to specify what’s a three-year vision versus what you’re trying to tackle in your upcoming annual plan, it's really easy for everyone to think they’re speaking the same language but actually be completely misaligned.

– Jiaona Zhang (“JZ”), CPO at Linktree

Cordova shares a specific example here: “For example, one of our 2024 goals was to make Linear the default planning tool for organizations, bringing together planning and execution into a single product. That wasn’t something that was going to happen overnight,” she says. “So it might be a longer-term horizon, but this year we made it a key investment area and shipped a ton of our high-level planning features — and we’ll keep chipping away at it next year.”

Writing the strategy doc: Who’s holding the pen?

The process of pinning the narrative down can look quite different depending on the founder’s style. Here, our group shares their experiences partnering with standout founders to shape the starting strategy doc:

It’s so important for one person to hold the pen at this stage, likely the founder or CPO. Don’t fall into the trap of document writing by committee.

– Jiaona Zhang (“JZ”), CPO at Linktree

- Ivan Zhao – thinking 10 years out: “Ivan has this incredible product vision,” says Katkar. “He's thinking about what Notion will look like in 5 years — even 10 years.” The team then works to connect that long-term vision with near-term priorities and capture it in a formal strategy document, circulating that for discussion with the executive team and other leaders at the company to make sure that they can cascade the information during the planning process.

- Christina Cacioppo – bringing others in: “Christina is the heart of Vanta. She drives forward the top-level vision, but she's not a command-and-control CEO. She's not dictating what to do,” says Case. “When we go into ‘C-suite week’ to kick off the annual planning process, it’s 100% collaborative, with all of us debating, discussing, and then as a group, aligning around the path forward,” she says. Here’s the process: The CPO translates Cacioppo’s high-level vision into a narrative document that looks three years out. “It describes where we think we're going, and the markets we believe we're going to open up — not concretely talking about exactly what we're going to ship,” says Case. Then comes the comment and debate period, first as a C-Suite, followed by the VP level to help fill in the details.

- Karri Saarinen – focusing on the story: For Linear, the focus is more near-term, which is appropriate given their size and stage. “Karri puts pen to paper in a one to two-page document. For him, it’s all about the story that we're telling next year to our customers and prospective customers,” she says. Next, they go over it as a leadership team, and Cordova works with the data and revenue operations teams to fill in the end-goal metrics like ARR and WAUs.

Picking investment areas: What aren’t you doing?

Next up is setting up the scaffolding that supports the company’s broad vision by articulating the levers or areas to invest in during the following year.

“The story that you’re telling and the investment areas you’re picking ultimately add up to your strategy,” says Zhang. Here are three pointers for getting that right:

- Limit your investment areas to 3-5. “At Stripe, Claire Hughes Johnson said that strategy should hurt. If it doesn't hurt, you’re not setting it effectively,” says Cordova.

- Remember what your English teacher told you: “Write and then cut 50% and then write again and then cut again,” says Zhang.

- Within each investment area, be clear what you are not investing in. Documenting specific choices is key for clarity. (Ravi Mehta goes so far as to create a “non-goals” section in his strategy docs.)

- Anticipate FAQs. “Include an FAQ of decisions that were debated by the leadership team, along with rationale on why certain decisions were made,” says Zhang. “In Linktree's 2024 strategy doc, we included answers to what we perceived would be commonly held questions from the team, like how do we approach competition? What verticals/personas are we focusing on? How much are we investing in our native mobile app vs. mobile web vs. desktop experiences? How are we changing our pricing and packaging?”

Strategy boils down to being a combination of what you’re not going to do coupled with the sequencing of what you are going to do.

– Jiaona Zhang ("JZ"), CPO at Linktree

Sizing up the competition: How do you stack up?

It’s critical to look at yourself and the market. “People tend to either overly index on competition — which is harmful because it doesn't actually tap into what your alpha is and why you might win. Or they just ignore it altogether and try to just march to the beat of their own drum, which might cause you to get lapped,” says Zhang.

The first step is to figure out what you’re positioning your product against. “That positioning affects how you sell, which affects how you price and package, which then affects what product you need to build,” says Zhang.

She lays out an example from Webflow: “We had to figure out if we were a better website builder for SMBs, like the coffee shop down the street? Or a professional website builder that replaces developers?” she says.

“We felt our user wasn’t the mom and pop shop — they could use Squarespace,” says Zhang. “We realized that we wanted to displace the budget traditionally spent on Wordpress developers or internal developers working on a marketing website. Whether it was an agency bringing Webflow in as evangelists or an enterprise company, those users needed more collaboration features and a lot of polish in the product, so that’s what we set out to build.”

It’s tempting to start sketching out your roadmap right away. But that goes last. There are all these questions you have to answer first. Who are you building for? How are they bringing you into the business? Who approves the budget? How are you positioning against the market? That informs the areas you invest in, which then informs what you tackle first in your roadmap.

– Jiaona Zhang ("JZ"), CPO at Linktree

Final check: Can you see your strategy reflected in the market?

“For me, the biggest thing to check for in the planning process is alignment on the story. Karri is Linear’s best marketer. And he really cares about the message. He’s the type of founder who wants to know how we’re telling our story out in the world and be the last person to see it before it goes out,” says Cordova.

“So what are the stories that he feels like we’re not telling? What are the messages we’re delivering well? What new ones does he want us to convey in the next year? For example, right now we’re really focused on telling our story around craft and quality.”

Cordova runs another check-in of her own on this front:

When we close a customer, we ask them why they chose Linear. I want a customer to be essentially parroting our messaging back to us in their answer. Otherwise, we’re not doing a very good job of conveying the story that we wanted to get out into the market at the start of the year.

– Cristina Cordova, COO at Linear

3. Fast follow with constraints

There’s one school of thought that it’s better to push teams to think bigger and get to that blue sky phase of planning that feels full of potential. But for this group of execs, that burst of unlimited creativity more often comes at a steep cost.

“Teams waste a lot of cycles dreaming big, only for it to come crashing down when they realize that they have half (or less!) the headcount they thought they’d have,” says Zhang. Case concurs: “I remember one planning cycle when we came back with 500 headcount asks across all the teams. And then the finance team was like, ‘Get it down to 100 total and then we'll talk.’ It’s much simpler to just start there,” she says.

Some companies try to take a half-step by asking teams to present multiple resourcing cases — what would you be able to accomplish with X staffing vs. Y staffing vs. Z staffing? “While directionally right, this practice in itself is wasteful,” says Zhang. “I like to work with the finance team to set a clear constraint that is defined by forecasting and budgeting.”

Here are some tips as you work through that process:

Err on the conservative side of headcount — for allocation and requests

Katkar shares the CFO’s perspective: "At Notion, I look at data for similar public companies when they were at our scale and benchmark where they were in terms of margin profile, ARR growth, and so on, up and down the P&L,” she says. “We don't necessarily need to fit the exact mold of any one of those companies. Notion’s business is unique. But it at least gives me a sense of who we’re closest to as I create a set of guardrails on cost for top-line guidance."

One principle to try to stick to as you’re running the numbers? “I really try not to take headcount away. I'd rather be conservative in how much we allocate at the beginning so we can give more as the year goes on," says Katkar. Zhang agrees. “Coming out of the ZIRP era, many teams are building the muscle of how to be more thoughtful where they invest when it comes to headcount,” she says.

Everyone tends to approach planning with infinite possibilities. But from a headcount perspective, it’s generally better to walk in with the mindset that you've only got a tiny bit more.

– Jiaona Zhang ("JZ"), CPO at Linktree

That conservative streak should cut both ways. For example, consider where you can start with a contractor instead of a full-time headcount request. “Using work trials at Linear has been very effective for us when we want to have confidence in making full-time hires,” says Cordova.

Also factor hiring delays into your plans. “I found people often plan as though that headcount they're asking for is already there,” says Katkar. “For example, say the monetization team is allocated five engineers at the start of the half. They plan their initiatives as though those people are already here, whereas, in reality, they most likely aren’t going to be contributing until several months later. At Notion, we have a very rigorous hiring process, it’s part of Ivan's ethos. And even when they’re in the door, they’re not at full productivity on day one,” she says.

Ramp time is not just for quota carriers. Approach planning by thinking about who’s in seat today. That headcount you’ve asked for likely won’t be up and running for some time.

– Rama Katkar, CFO at Notion

Linear has faced similar timelines. “We benchmarked how long it takes to go from end-to-end in our hiring process versus at another company. Linear’s is much longer,” says Cordova. “That’s why we've always had a larger recruiting team than is usually warranted for a company of our size. When I was at Notion and Stripe at 40 people, we had zero recruiters. At Linear, we have four recruiters and are hiring a head of talent. These are all things we're doing earlier than companies of our size just because we invest so much more in every hire.”

Get teams to quickly surface what they can’t do

With that tops-down guidance set, Zhang recommends asking teams to immediately flag what they don’t believe they have capacity to do with a single ask for staffing.

“If you start to see that there isn’t much in the ‘not-able-to-do list,’ you need to ask yourself if your teams are being realistic about what they can accomplish — and whether you should be more ruthlessly cutting,” she says.

The “Tell me what you can do in 3 or more resourcing scenarios,” ends up wasting time. Getting your team to instead surface what they don’t have capacity to do is one of the best tools to identify what you’re not prioritizing and whether the business is okay with drawing the line there.

– Jiaona Zhang ("JZ"), CPO at Linktree

4. Get to a shared understanding of what success looks like

An often overlooked step is openly discussing how the leadership team would feel if the team actually did hit its targets.

“Sometimes you set a goal and you hit the ball out of the park. I remember at Stripe once we were far above our number and feeling proud — but then the founders responded that it sounded like we set the bar a little too low,” says Cordova.

This is the biggest challenge that Katkar has seen crop up in the planning process. “People want to be on a winning team. They want to feel successful. On the other hand, the CEO wants teams to think more expansively and push the limits. There’s an inherent conflict here,” she says. “The best thing is to just explicitly have that conversation.”

Consider your menu of options. “Is it early-stage, where making 50% of the goal was great because the goals were so ambitious? Or is achieving 70% of the goal is ‘green’ because it was a bit of a stretch target? Does it need to be >90% achievement? Or is it prepping-to-go-public and you’ve got to beat — or at least hit — that number?” she says.

The mismatch in expectations around success can result in some of the most demotivating QBRs you’ve ever been a part of. There's a difference between pushing your team and making them feel you had unachievable targets from the very beginning.

– Rama Katkar, CFO at Notion

Write out the math of your business

The macroeconomic changes of the past few years have reshaped startups’ aims, leaving many founders scrambling to shore up their revenue and profitability stories.

“A surprising number of startups fail to make an intentional connection of what they’re building to what they can charge for it and how they’re going to monetize it,” says Case. “It’s the step that gets skipped the most commonly in companies large and small. It's often left as more of a vague idea to figure out later. Now it's a whole different ball game if your North Star is not revenue, but if you're trying to drive revenue, this is the conversation you need to have, as early as possible,” she says.

“Even if it’s your first year, your first product, your first sale, you still have to develop a basic understanding of how the math of that sale is going to work — and how that might translate into the next set of scaling activities you take on,” says Case. “It could be just half a page, but write it out. Get the math to work and justify what it looks like when it grows 10%. That’s the foundation of planning. If you skip that, it's all kind of pointless.”

Regardless of size and stage, you have to write out the math of your business. It doesn’t have to be the big process that we do at a Series C company like Vanta. It does, however, have to make sense. All businesses are subject to the laws of math and physics.

– Stevie Case, CRO at Vanta

Case shares a more tactical blueprint for this exercise: “Think through the single-buyer perspective — in a very concrete manner — about where the dollars are going to come from and how you would get somebody to write a check for what you're building:

- What is the persona of the person we are going to sell that to?

- Does that person have budget?

- If that person does own a budget, what are they typically spending it on?

- Are we displacing a tool that they already buy with what we're building because it's better?

- How would our buyer think about the math behind that purchase? Would they pay more? Would they pay less?

- If they don't have budget, who would they get budget from?

5. Ensure your org chart reflects your strategy

“One of the recommendations I make that people tend to find counterintuitive is that you should time-box the time you spend planning, and instead invest that time in designing the right org,” says Zhang. “It’s invaluable to be able to have the right leaders in place who understand what you’re trying to achieve.”

Org design is how you deliver on your plan. Instead of meticulously planning all of the “what,” the right org design will give you the ability to hand a talented group of people a new goal, and have them continuously come up with the best way to achieve it.

– Jiaona Zhang ("JZ"), CPO at Linktree

“This way you can fund an area that’s dedicated to solving a problem and driving a business goal, as opposed to constantly spending your time moving people around to fund a feature or product initiative,” she says.

There will inevitably be unclear boundaries. “It’s impossible to design an org with no overlap in surface area, so spend the time upfront to articulate how teams work together,” says Zhang. “This is a meaningful thing to do in planning, as opposed to spending the time trying to get to a false level of precision around what each team is actually going to do.”

Make sure strategy flows into your org chart

To bring to life this concept of how strategy should flow into your org chart, Zhang sketches out an example from Webflow.

The vision was to build the world’s most powerful visual development platform, which broke out into a few key strategies:

- Make the core product great and very scalable.

- Target enterprises that want their marketing sites to have beautiful visual design and also be super functional.

- Get to those customers by empowering agencies to bring Webflow into these types of companies.

Critically, that then resulted in some org chart reshuffling, around four new product teams:

- Core product team: Working on core features that made Webflow more visual and powerful

- Enterprise and collaboration team: Working on features that would allow enterprises to make use of these functionalities and easily collaborate with others in Webflow

- Ecosystem team: Enabling technical folks with APIs to build more advanced sites, while also working to match agencies and freelancers with companies by building out an entire marketplace

- Lifecycle team: Understanding which of the two personas users were (agencies or in-house teams), following them through the product and tailoring it to meet their needs.

“This org structure enabled the teams to be clear on their mandate and understand how it fit into the broader strategy,” says Zhang.

Shape your org chart so it’s as unique to your business

“We have a pretty opinionated take on org design at Linear,” says Cordova. (For a deeper-dive here, we recommend checking out this writeup from Linear’s Head of Product, Nan Yu, on why that has led to a less-than-symmetrical org chart.)

“We have an engineering manager who has 10 reports right now, and thinks he could get to 20 without being too overwhelmed. As Nan said in his Review article, five to eight reports is not the ceiling. That number came from a specific context, from the High Output Management and Jeff Bezos ‘two pizza box’ teams approach,” says Cordova.

“You need to figure out the right number for your team. For us at Linear, we primarily hire senior to staff level engineers, and most of them don't require a lot of people management. Because each engineer can take on lots of scope, our structure also allows each project team to be quite small — often two to four people. This is very much an experiment, but it’s working for us so far.”

Zhang and the team over at Linktree are doing some of their own experimenting: “We don’t focus on traditional brand campaigns that are about Linktree. Instead we focus on telling the stories of our Linkers, because that’s ultimately how we drive growth,” she says. “When Steph Curry has a well-crafted Linktree, everyone in the sports industry pays attention. When Sabrina Carpenter and Billie Eilish broadcast their Linktrees, their fan bases will try it out too — not to mention other musicians. With the White House on Linktree, politicians and government organizations see value in our platform.”

Linktree drives these relationships through a creator partnerships team and co-creates content with creators through the social team — both rolling up to marketing. “Then, the product needs to feel cohesive: from seeing social content that resonates with the user driving, to a personalized landing page and custom templates through the onboarding flow — which is why paid marketing and brand design are centralized and sit together under the product function,” says Zhang.

Take the time to deeply understand how you’ll grow the business. If you know what drives your growth, you can actually optimize your org chart to make collaboration more efficient.

– Jiaona Zhang ("JZ"), CPO at Linktree

Think about how you’ll scale

“When Claire Hughes Johnson joined Stripe, we were in this period where we couldn't get back to our customers for four or five days. We had every person in the company doing a support rotation because we didn't have enough people to respond to tickets. We were clearly growing very rapidly and didn’t have the scale to support it,” says Cordova.

“So Claire did a bottoms-up and a tops-down analysis of how big the company should be. She looked at the ratio of how many tickets people at other companies can do, and then how that mapped to our volume expectations. She concluded we needed about 300 more people, right away,” says Cordova. “Clearly, that wasn’t going to happen overnight, particularly with our hiring bar. So that led to a strategic decision to outsource support to help us scale without having to grow headcount that rapidly.”

Cordova’s scaled-down version of that exercise at Linear’s size involves going around to every hiring manager and asking three questions:

- Are there any areas in the business where you would feel like if we lost a particular person it would be a disaster because you're either already really understaffed or lacking redundancy?

- Thinking about an optimistic world where you could have as much talent as you wanted that was willing to work for Linear, how many people would you add to your team right now?

- How many people would you add in the next six months? By the end of this year?

6. Make space for deviation and disruption

Your carefully crafted plan will inevitably crash into reality, whether it’s a new entrant in the market, changes in your customers’ behaviors, or cutting-edge technology. This group shares their strategies for dealing with curveballs and staying close to your plan as the year unfolds:

Plan for disruption from AI

The launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 threw a unique wrench into the already complicated annual planning process: Where will AI fit in? There are implications for staffing, product roadmaps, budgets for new tooling, R&D, and so much more.

“There will be a lot of tough conversations around this in the years to come,” says Zhang. “What's the new steady state of marketing spend when there are so many tools now to scale asset or content creation? Or customer support — we’re using bots at Linktree, and it’s working very well.”

You won’t be surprised to hear that each of these execs are approaching incorporating AI differently. Read on for some of the forward-thinking experiments they are working into their planning processes:

Linear: Deciding what work to outsource

“Many teams are making the shift over to AI-powered customer support. But the first thing our founders told me when I joined Linear was that we are never outsourcing support,” says Cordova. “Our customers are technical. They would much rather read the manual rather than reach out. So if they're reaching out, they're probably desperate, and they want to talk to a human being,” she says.

However, AI has made an impact on Linear’s plans in other ways, like in sourcing candidates. “I initially didn’t want to hire a sourcer. In my experience at other companies when we've hired sourcers, they all want to be recruiters eventually or go into other roles. You’re constantly filling a leaky bucket,” says Cordova. “So our recruiters have been using ChatGPT to create booleans for search on LinkedIn and things like that. And if we find that AI is not quite there yet, we’ll hire a contractor or an agency to pitch in.”

Vanta: Modeling added efficiency

“We model for the team to hit a certain percentage of a monthly quota, but the reality now is that elements of that work can be done by AI or by tooling,” says Case. “We will continue to need many, many humans. We just want to make them even more effective. So as we build our model, we are also building in budget for AI-powered tooling as a multiple to the efficiency or the productivity of certain types of resources,” she says.

“As I go into building the sales capacity model for 2025, here’s one of the things I’m trying to articulate: We're going to spend X dollars on AI-powered things. We need headcount for a team to build those things. And with that, I expect to get X percentage more productivity out of my salesforce for it. So there's an ROI built in — I think that that is increasingly where revenue teams have to go,” says Case.

She has another new idea as well: “We typically don't have engineers in revenue,” she says. “So I’m proposing to create a new function inside my revops team that we're calling ‘AI Operations’ — with a product person, a designer and an engineer who are just going to build AI-powered workflows for us internally.”

Notion: Putting AI into the P&L

Notion’s made an aggressive bet on incorporating AI into the product, getting an incredibly early start out of the gate in late 2022 and just recently, releasing a major update (complete with an animated face that’s ‘The New Yorker’ meets Clippy).

“Every team within Notion, in some shape or form, is thinking about how AI is impacting the business,” says Katkar. “It lets us think very differently than just trying to copy what our SaaS peers are doing. Because we can enable so much in our product with AI, it helps us leapfrog our competitors that are maybe more specific point solutions.”

Then there’s the impact on the bottom line. “For Notion, AI is driving revenue. We did launch AI as a separate SKU, and it's doing quite well,” she says. “But I also run the business technology team, which manages quite a bit of the internal tooling and procurement, so the opportunities to utilize AI-enabled tooling to reduce costs is also on my mind these days,” says Katkar.

“We also have a separate contribution margin P&L for the AI part of the business — the vendors that we use, the models that we use, all the costs associated with that,” she says. “I do not pretend to be an engineer. They're making decisions across vendors almost daily when they're thinking about product development. It’s a very fast moving space, so there’s rapid change,” she says.

“The way I’ve set it up is more like, ‘Hey, I would like us to hit this contribution margin. And how you guys get there is kind of up to you. Every month I'm going to show you where we are versus where we thought we'd be, and let's talk about how we should handle it.’”

Craft the right check-in cadence

Once your planning process is closed and the calendar flips over to the new year, it's crucial to establish a regular cadence of check-ins to monitor progress and make necessary adjustments that will keep your strategy doc from going stale — and ensure that all those hours of planning translate into tangible results.

Part of this work stems from managing expectations at the start. “You need to understand the Goldilocks principle of fidelity for your org — the level of detail that’s just right,” says Zhang. “Set the expectation that things should be higher fidelity earlier in the year and get fuzzier as the year goes on. You're much more likely to be right for H1 and you're very unlikely to be right for H2. If you're tracking way higher or way lower than you anticipated, you're going to have to course-correct. You should just accept that, instead of panicking when things turn out differently or wasting a ton of time trying to get to false precision and then throwing everything away,” she says.

With that mindset locked in, keeping close tabs is crucial. “No matter how small you are or what stage you're at, to create this time, place and cadence for a check-in and a reminder of what you were trying to do in the first place,” says Case.

Usually what goes wrong is that you get into the year, people get busy, you get distracted — and the plan goes completely by the wayside. That’s when you fall into this week-to-week, month-to-month pattern of, ‘Well, what should we do next?’ and being reactive to whatever's right in front of you.

– Stevie Case, CRO at Vanta

Katkar shares Notion’s approach here: “We do monthly business reviews and a weekly ARR meeting. The MBR is more of a formal check-in with the entire executive team and the key business units,” she says. “The weekly meeting is with a subset of the exec team. It’s basically a weekly business review that's pretty in-the-weeds in terms of how things are progressing versus plan and the trends that we're seeing. If we see a trend for a few weeks in a row, we want to dig into that and understand.”

Here’s how Zhang stays on top of things at Linktree: “We run our 5-week max annual planning process. Then we hold QBRs, which have become a very standard practice in tech. But I think people tend to think of these as a very intimidating, heavyweight exercise. I just call it a ‘look back, look forward’,” she says.

“We have a scorecard template for each quarter. It has three to five of our key cross-functional goals. Every single week we have a scorecard meeting, which is a lightweight check-in where you grade your goal and tell everyone if you're on track, at risk, or off track,” says Zhang. “You come in with a very clear ask about what help you need if you're trending yellow or red. That way, no one is surprised in the QBR. We’re able to make decisions and course corrections as we go. It’s a great way to get moving on things that are unexpected, like a competitor announcing a big launch.”

Duplicate on NotionHow to handle deviations from plan:

Here’s how Case runs things at Vanta: “For my revenue org, our AOP plans every month by segment and metric. We can and do still make adjustments within the year — but we don’t change these target numbers,” she says.

“We do, however, set guardrails that indicate we should deviate from plan. For example, if a specific sales team or segment is above 100% attainment for two months, we should add capacity even if it's not in the plan,” says Case.

She points to an example on the downside: "We introduced an early product to a new segment and found our win rate was only 6% for this specific product-buyer combination. Generally, a win rate below 30% means salespeople are wasting time and you need an unsustainable amount of pipeline,” she says. “In this case, the solution wasn't to fix sales, but to immediately stop selling this product to this buyer. We needed to revisit our product strategy, questioning if we were targeting the wrong audience, if the product itself was flawed, or if our entire strategy needed rethinking."

Another tricky spot can be figuring out if your efforts would be better spent leaning into a strength or shoring up a weakness. Here’s Cordova’s approach at Linear: “Every month we effectively do a re-forecast. So far this year, we've been far ahead of forecast. We have a lot of customers adopting our most expensive plans, and retaining within the business over time, so we don't have a lot of churn,” she says.

“The question that opens up is do we invest more in customer success? If the expansion game is really working for us, should we really lean into it? But it’s just as easy to argue the opposite. If net-new growth isn’t changing as much, should we put more into that to make it better? We are more of a throw-gasoline-on-what’s-working type of team, but you have to figure that out for yourself.”

Start prepping the groundwork for next year

It’s not just about making adjustments to the actual plan, but to the process itself. Too many teams skip over the chance to capture learnings that can inform and improve planning for the following year.

“Even if it’s all wrong, it gives you a chance to say, ‘Oh, we were completely wrong when we made this plan. Here's what we've learned since then, and here's how we've recalibrated,’” says Case. “Without this process, all of those learnings are lost to the wind.”

Consider using the following questions this time next year as you assess what you want to carry over and what you want to change:

- What worked well in our planning process this year?

- Where did we encounter bottlenecks or challenges?

- Did our plan accurately predict our performance? If not, why?

- How well did our planning process accommodate unexpected changes or opportunities?

- What new tools or approaches could we incorporate next year to improve our process?

It’s also easy to only think of annual planning as a fleeting season. But it’s helpful to reframe it as a process that you’re gathering inputs for all year long.

“At Vanta, we have a C-suite sync every week that’s more of an open forum. And that’s where we're discussing these strategy topics throughout the year — everything from the competitive landscape to opportunities and challenges in the business,” says Case.

“We also do a monthly business review with GTM and EPD where we talk about opportunities for TAM expansion, and where we might start to pick off other competition. We also have a product advisory board and a customer advisory board which is an opportunity for us to take some of those nascent ideas and run them by our existing customers,” she says.

There's this ongoing dialog throughout the year so that when we all sit down at that annual planning exec offsite, we will of course each come with our own proposals and point of view — but we've basically spent a year talking about it. So by the time we come together to make those decisions as a group, we have laid a huge amount of groundwork.

– Stevie Case, CRO at Vanta

“That’s why we end up extremely well aligned about those areas of investment. We still have to nail down the details and come to certain areas of agreement, but our annual process is built on the last year of learning, debate and discovery about what else is out there for us.”