It’s the most wonderful time of year — for anyone not involved in strategic planning that is.

While still hoping to give their team a final boost of motivation to hit those stretch goals before Q4 wraps up, many founders are undertaking the ritual of crafting plans for the next calendar year. It’s a time to review and reflect on lessons learned from these past 12 months, with the hopes of turning those insights into action for the next plan period.

Even in the best of times, annual planning is no founder’s favorite activity. From sorting through a tangled web of stakeholders and setting realistic yet still-motivating big goals, to balancing short-term needs with a long-term vision, it’s always a messy process.

But as you’ve undoubtedly seen in the recent headlines, as the year comes to a close, founders find themselves facing some tough headwinds that are further complicating this annual exercise — whether it’s the public markets, waves of layoffs at bigger tech companies, or fears of contracting customer spend.

This year has been yet another reminder of how the tech ecosystem can change on a dime, disrupting even the most carefully-laid plans and clouding potential paths forward. As a founder, it’s a daunting challenge to put together an annual plan that attempts to forecast an entire year ahead, especially at a time when even the next few weeks seem uncertain.

But regardless of how the coming months will unfold, what we’ve found through talking to founders and experts over the years here on The Review is that time spent thinking about your business’ future path is never wasted. The classic Eisenhower quote that “plans are useless, but planning is indispensable” rings true for a reason. But with so many moving parts and changing variables, it’s easy for founders and startup leaders to feel overwhelmed by the task of putting a plan on paper.

That’s why we’ve combed our archives to compile six unique approaches to end-of-year planning. We’ve tried to surface the fresh tactics, different perspectives and tested frameworks that have led teams through turbulent times — with hopes that they will help put you and your team in the right mindset to tackle whatever the upcoming year brings.

Looking for a quick way to get started? Grab our Notion template for OKRs here:

#1: Lean on this framework to make sure you’re sharing enough context.

No matter what’s going on in the macro environment, what doesn’t seem to change year after year is the persistent roadblocks that all teams face when it comes to annual plans.

A couple of years ago on The Review, Lenny Rachitsky and Nels Gilbreth teamed up to create “The W Framework” with hopes to save other teams from painful planning cycles. (Rachitsky is a former product lead at Airbnb and author of the immensely popular product advice column Lenny’s Newsletter, while Gilbreth is the former Global Head of Commercial Strategy at Eventbrite and current founder of goal-setting startup Daydream.)

They found that a common theme emerged from nearly all the bad planning processes they’ve observed: a basic lack of understanding of roles. More specifically, the common questions that end up plaguing teams are:

- Who should have a say in the strategic plan?

- What exactly does each stakeholder need to deliver, and to whom?

- Who sets the timelines?

- Who holds everyone accountable?

- Who makes the final call?

When these were left unanswered, Rachitsky and Gilbreth found it led to the most chaos and ultimately, disappointment during the planning process. “Planning is hard because it’s inherently different from other exercises your organization takes on. Rather than focusing on day-to-day execution, it requires a large number of people to think about a variety of possible futures, align on one single future and then plot a concrete course to get there,” Rachitsky and Gilbreth say.

The framework is made up of a four-step process, but today we’ll focus in particular on the first step: adding context.

- Context: Leadership shares a high-level strategy with teams

- Plans: Teams respond with a proposed plan

- Integration: Leadership integrates into a single plan and shares it with teams

- Buy-In: Teams make final tweaks, confirm buy-in and get rolling

According to Rachitsky and Gilbreth, this first step is crucial to the success of any strategic plan. Almost always, they’ve seen well-intentioned strategy sessions fall apart when teams aren’t clued into key background information about the business. That’s why the two suggest that leadership dedicate time to providing as much context as possible.

As an example of what can go wrong when there’s too little context, they cite a planning cycle where all the leaders in a business unit received a synthesized plan for the year ahead from all the various teams in the unit. This plan was put together from the bottom up — with each team’s more focused plan getting rolled into one, giant plan. But as a result, there were five times as many priorities as there were teams, and individual team strategies often pulled in opposite directions. The issue, at its heart, was that teams lacked context.

“Teams need to know what investments need to be made now in order to set the company up for success down the road. They also need to know what the biggest risks to the business are. Leadership has the firmest grasp on these things, and it’s on them to communicate that during the planning stage,” they say.

Teams need context to contribute to the annual plan. They need to know what the company absolutely needs to nail over the next year.

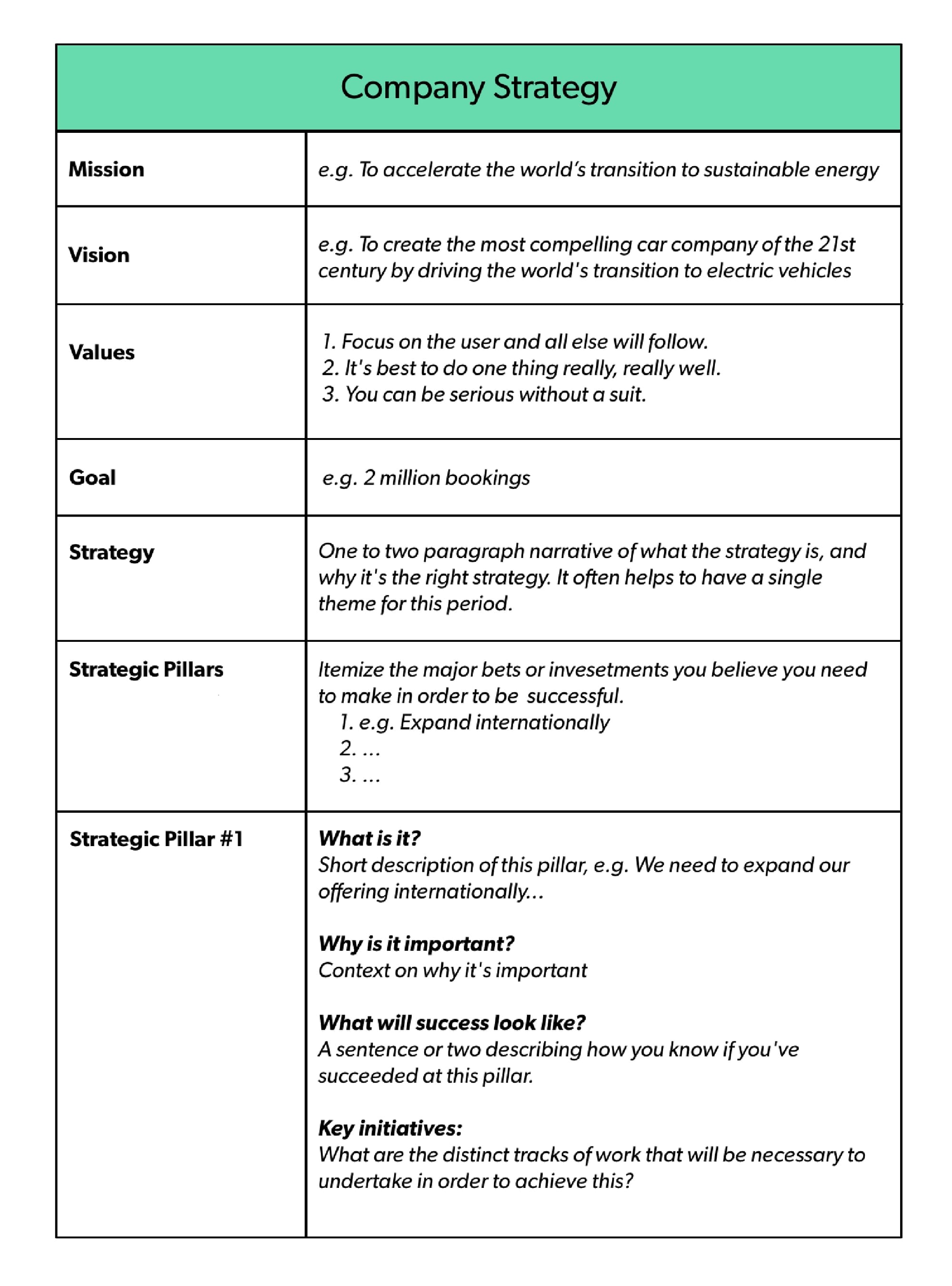

One of the best ways to share this context with teams is by creating a company strategy document, a deliverable that codifies the strategic plan. Leaders can fill this out and share their first draft with teams, so they can collect feedback from teams in the next step of the framework. Rachitsky and Gilbreth recommend using this template:

Read the rest of The W Framework and get access to more of their strategic planning templates here.

#2: Sick of OKRs? Try NCTs.

It used to be revolutionary to use OKRs — the goal-setting system first introduced by Andy Grove at Intel, and later at Google by John Doerr — as the mile markers guiding any leading company strategy. For good reason too: It was designed to get executives and teams aligned on a handful of shared priorities that all contributed to key business objectives.

But just as startups naturally evolve over time, the thinking around OKRs has also changed, and many have soured on the format altogether. Count Ravi Mehta in that camp. While in a previous life he worked as a VP of Consumer Product at TripAdvisor and CPO at Tinder, these days, he’s sharing his wealth of knowledge as CEO and co-founder of Outpace, a leadership coaching platform.

Mehta’s work zeroes in on product strategy, particularly how to optimize it. But he’s spent a lot of time working in organizations with OKRs, and he’s not a fan for a few reasons:

- Fuzzy objectives: The way teams define objectives is not tied back to strategy very well.

- Hyper-focus on metrics: As we’ve heard from previous leaders in this article, a hyper-fixation on metrics puts too much emphasis on the goals as the destination, and not the strategy.

- Aspirational thinking: OKRs are intentionally set to be aspirational. If only 70% of a goal is completed, the quarter is considered a success. This is a probabilistic approach that things might get done, when what teams really want is a process that’s deterministic.

He’s devised another acronymic framework to rethink your strategy planning document: NCTs (Narratives, Commitments and Tasks). We’ll break down what each key component means, including a sample to get you started.

Narratives

“The narrative is similar to the objective in an OKR, but teams are specifically recommended to make it longer. Describe the strategic narrative that the team wants to accomplish in at least a few sentences. Create a really clear linkage between the goal that’s being sent, and the strategy that goal ladders up to,” says Mehta.

Sample narrative:

Today, travelers who navigate to Tripadvisor using Google are often leaving and re-entering Tripadvisor multiple times a day. We can build a more retentive user experience by enabling them to organize, share and access all their trip content, no matter what device they are on, or where they are in their planning journey. As a first step, we’ll increase awareness and usage of the “saves” feature and a new trip plan feature.

Commitments

“Each narrative will have 3-5 objectively measurable commitments. The word commitment is used very deliberately here — you should plan on achieving 100% of those commitments so that your team knows exactly what they’re expected to accomplish at the end of the quarter. Commitments are the evidence that the team has made progress on the narrative,” says Mehta.

Sample commitments:

Increase the number of unique trip savers from X to Y by the end of Q1. Increase saves per saver from W to Z by end of Q1. Increase 7-day repeat rate for overall traffic (due to increased save usage).

Tasks

“What work needs to be done in order for the team to achieve its commitments and make progress on the narrative? Tasks are the most fungible piece of a team’s NCT — the idea is to give teams a warm start on making progress on their goals. If at the end of a quarter a team has achieved all of its commitments, but none of the tasks — that’s a successful quarter. On the other hand, if a team completes all of their tasks but none of their commitments, that’s just checking the box. It’s not a successful quarter,” says Mehta.

Sample task:

Launch new backend saves service. Launch saves funnel health metrics dashboard. Test suggesting defaulting trip names. Implement single-factor test save icon.

To bolster the NCT strategy, Mehta also suggests building “non-goals” into your strategy documents as well. “This should cover elements or questions that came up during the strategy process that were particularly controversial. Be very clear about what decision was made and where folks disagreed but committed,” he says.

As part of the strategic planning process, you’re making choices. It’s important to document those concrete choices — not just that we’ve chosen to do A, but also to explicitly reinforce that we’re not going to do B.

Read on to learn all of Mehta’s lessons for leaders, including how to build a product strategy stack

#3: Don’t skip straight to the metrics — create the scorecard by which you’ll judge success.

Founders have more data about their company’s performance available at their fingertips than ever before. But real-time analytics and robust data rooms can actually lead founders astray, pulling them into the tactical weeds of targets and metrics that can overlook the bigger strategic questions.

CEO of CoderPad Amanda Richardson has seen too many startups get swallowed up by messy data usage. Richardson (who used to serve as the Chief Data and Strategy Officer at HotelTonight, which was acquired by Airbnb in 2019) is a big proponent of mapping out high-level questions you need to be answered before any metrics are put into place.

The most common mistake she sees is teams aimlessly digging through data, looking for the story. With no clear point of view, though, she says they’re left chasing a moving target.

“You need to start with a specific question to answer or hypothesis to investigate,” Richardson says. “A lot of times, people will launch a product and then say, ‘How's it doing?’ Rather than saying, ‘Our product goal is to convert from this to this. Or grow the top of funnel or move the bottom of the funnel. Or increase our revenue per user.’”

In other words, without a clear agreed-upon goal, you run the risk of rewriting history as the data comes in. ”It’s easy to take wins wherever you find them. Maybe you said, ‘Our goal is to grow first-time users by 10%,’ then you see that feature is used by repeat users 30%. All of a sudden you're saying, ‘That's a big win! We got 30% of repeats!’ People lose sight of their goal all the time.”

That’s not to say that you have to turn a blind eye to new insights that will inevitably surface. But keep your focus trained on what you set out to accomplish. “When you ask data people how a product or feature is going, they’ll almost always come back with a list of fun facts. Don’t confuse those secondary metrics with your top metric,” says Richardson.

The key to effectively consuming data is to clearly stipulate what you’re trying to accomplish and how you’ll define success. Everyone agrees at 60,000 feet. But once you take it into the details — “What are we going to high-five over in 30 days?” — people are not so clear.

To weed out any secondary metrics or distracting numbers, Richardson suggests creating a scorecard that will define success, with SMART goal-setting in mind (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and timely).

But an even more radical take around metrics is to deprioritize them from the planning process completely.

“The thing that I've noticed about OKRs is that the objectives aren't prioritized in most companies,” says Jeff Lawson, CEO and co-founder of Twilio. “At most companies, the energy of OKRs is really around the key results. Everybody gets very focused on the metrics. But metrics are, in my opinion, the least important part of an annual plan because they’re not very strategic.”

The metrics tell us if we're on the right path. But charting the right path is actually the hard work.

Instead, Twilio uses a system called BPMs — big picture, priorities and measures.

- Big picture: 2-3 sentences about what the team wants to accomplish in the next 5-7 years, based on what leadership has outlined in their long-range plan.

- Priorities: 5-10 efforts to prioritize over the next 12-18 months. Think of this as what needs to be done to get to the big picture.

- Measures: Markers that tell you if you’re making the progress you want toward the priorities.

Read more of Jeff Lawson’s contrarian advice about how to fine-tune your growth strategy and ultimately scale your business here.

#4: Stay on your toes by planning for unexpected scenarios.

Sometimes, life throws a curveball. There are challenges that founders routinely face, like a product launch falling flat or a new competitor emerging on the scene. The best leaders build their annual plans with this in mind. But then there are the pandemic and global conflict-type scenarios that no one could have dreamed up on their own

Upheaval can be paradoxically paralyzing, making a “wait and see” or a “stay the course” approach appealing. And while macro-level changes seem to be taking place at a dizzying clip, the micro-level of what’s happening in a business — signed contracts, churn and so on — still may be slow. But given their general optimistic streak, founders need to be especially aware of the dangers of delay and doing nothing.

When facing a broad range of possibilities — from a quick recovery to a sharper downturn — it’s important to forge plans for a few different outcomes so you aren’t caught flat-footed when that time comes, which is why an advanced scenario planning framework can come in handy.

Strategizing for the unpredictable isn’t going to take the place of an end-of-year plan, but it is an additional step you can take to safeguard any strategy you do put in place. Below we’ll recap a five-step scenario planning exercise to get you thinking about how you can adjust your operating plan to respond as the year unfolds. (Note: This framework is borrowed from the field guide we put together for founders when the COVID-19 pandemic first upended our lives in 2020 — featuring a wide range of perspectives from leaders and investors who had seen uncertain times before.)

- Step 1: Identify key uncertainties. Outline 6-10 key uncertainties introduced by the current scenario. Think about what elements would have the most profound impact on your company’s prospects and strategies.

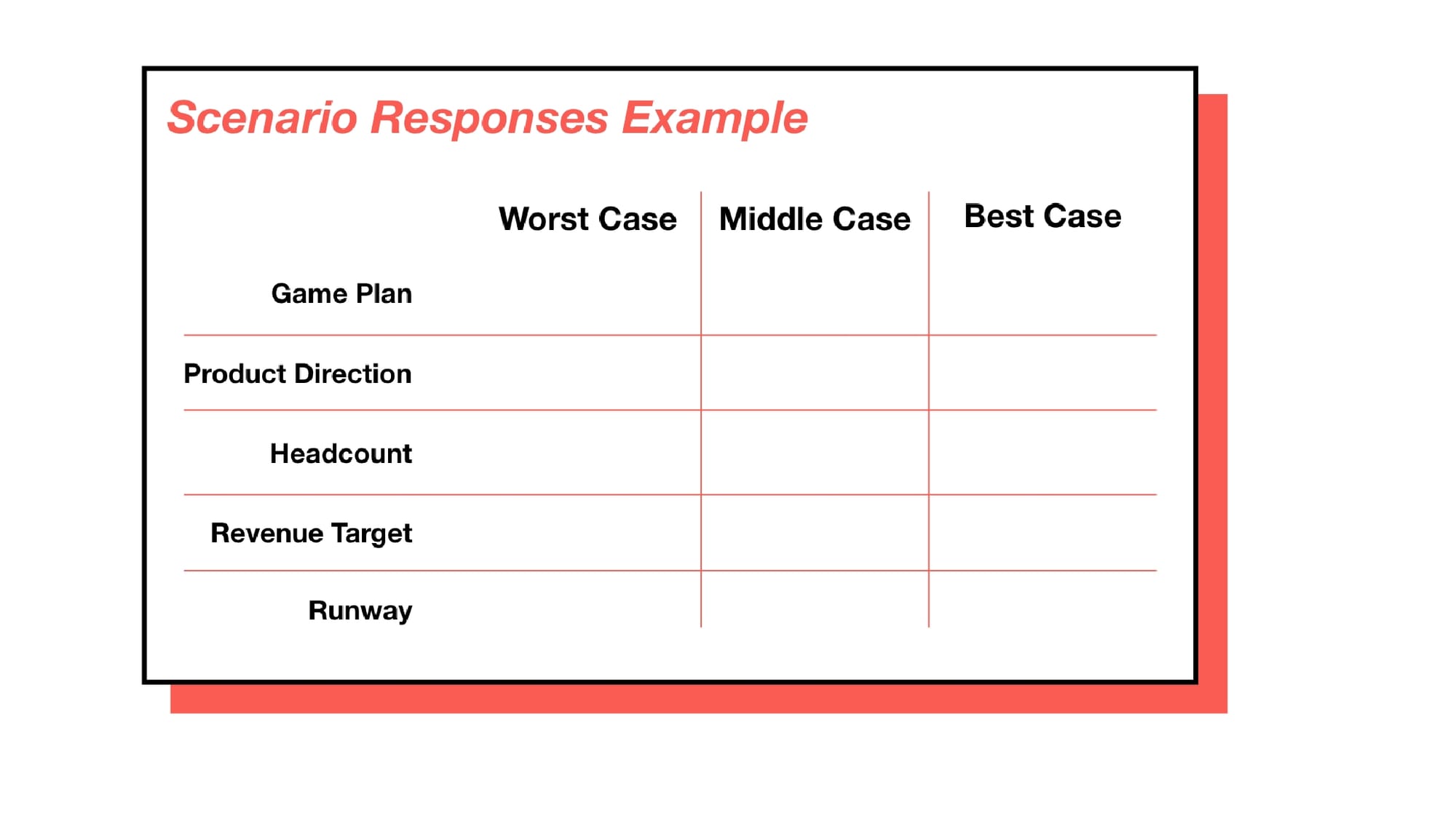

- Step 2: Bucket them into different scenarios. Outline a worst case, middle case, and best case. (Patrick O'Shaughnessy offers a helpful trio-based metaphor: blizzard, winter or ice age.) To bring each of them to life, we suggest giving each scenario a name and a narrative, so they feel less abstract and more tailored to your company’s situation.

- Step 3: Craft responses to each. If your scenarios describe where the situation is heading, your responses should answer the question, “now what?” Use something like the table above that will organize how your overall business plan will change according to each scenario.

- Step 4: Look for trigger points. These are things to monitor for that will make it easier which path to choose should one of your planned-for scenarios come up. The first is macro trigger points. This includes high-level market data like job loss trends or small business closure rates. There are also internal trigger points, or things inside the business to keep track of. Examples here look like customer churn stabilizing or dropping or a pick-up or drought of inbound sales leads.

- Step 5: Revisit, revise and repeat. Make sure to update your thinking at a certain cadence, archiving your old uncertainties, scenarios and responses and copy and paste the builder template into a fresh version. Here’s why it’s worth repeating: “Once people decide on a model, there’s a risk of becoming entrenched,” First Round partner Josh Kopelman says. “Writing out your assumptions in a living doc forces you to recognize what’s changing.”

If you’re curious to try this approach out for yourself, duplicate this template that our friends at Notion helped us develop, which includes example responses for a fictional corporate catering service reacting to the onset of the pandemic.

#5: Avoid the “set it and forget it” trap by building a ritual for checking in on plan progress.

You’ve likely encountered a pattern like this before: A rapidly-growing startup team encounters confusion about priorities, a lack of alignment, and wasted efforts, so someone suggests the company implement a goal-setting framework. After a lengthy process of setting OKRs for the beginning of the year, the wheels slowly start to come off.

This is why Kevin Fishner, a former Chief of Staff at HashiCorp is a massive proponent of organizing strategy plans into bite-size timeframes.

“After OKRs are set, there's no ritual for reviewing them, so they quickly get out of date. Then employees start resenting them because the effort to actually create the goals was a waste of time — and OKRs slowly die because no one looks at them anymore. Expectations aren’t enough. It’s the ritual that keeps the priorities top of mind and folks focused on what's important,” Fishner says.

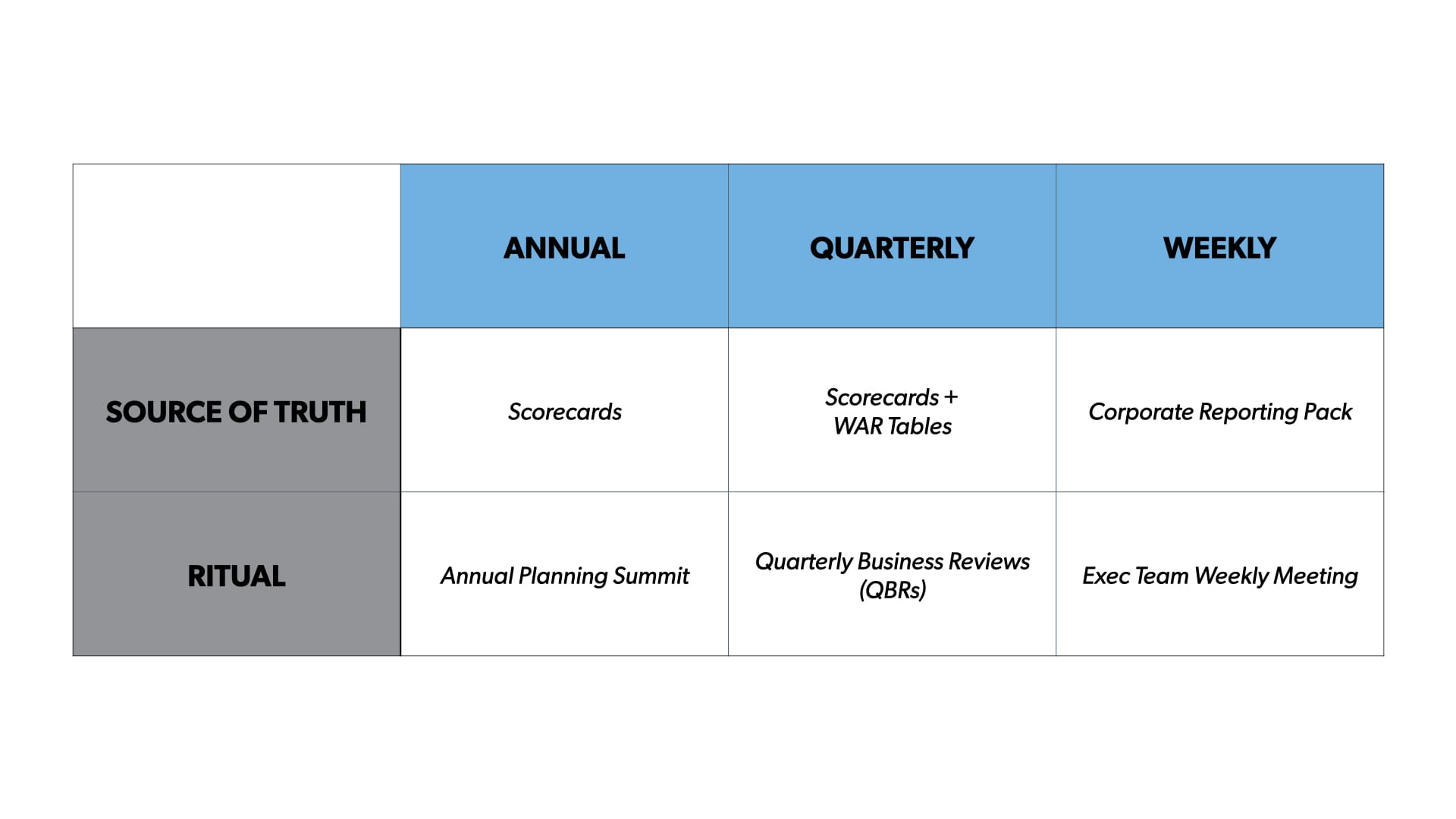

HashiCorp dubs this ritual process as “operating cadence.” The way Fishner sees it, operating cadence has three speeds: annually, quarterly and weekly. Each speed is built on two components:

- 1. Sources of Truth: define success in a clear, ideally quantifiable way

- 2. Rituals: a consistent practice to review that source of truth and build accountability

The tip here is to set up internal processes for checking in on your strategic plan, so you don’t stray too far off course from initial goals. “Oftentimes companies will focus on the source of truth and not the ritual — and that's one of the biggest mistakes that you can make,” says Fishner. “The purpose of an operating cadence isn't to dogmatically stick to goals set at the beginning of the year. It's a ritual of reflection and introspection.”

Check out this useful framework that HashiCorp uses to make progress and stay accountable at an annual, quarterly and weekly level:

“If you get it right, this system can set clear expectations, track performance, and identify improvements to make along the way,” says Fishner. Let’s take a look at an example of how the two components of a scorecard work in tandem to keep HashiCorp on track with reflection and accountability in its planning process.

In a weekly review of a quarterly strategic plan, the team compiles the superset of metrics agreed upon in the annual plan into what they dub a “corporate reporting pack.” This is the scorecard that steers the team as the source of truth.

The ritual is a weekly hour-long exec team meeting broken up into 15-minute time slots. The first 15 minutes are spent reviewing the insights on the metrics. For the other three 15-minute slots, a guest speaker comes in to present on an action item identified in the previous quarterly business review — another level of accountability to make sure that HashiCorp is following up on the challenges that surface.

Taking this fine-tooth-comb approach places the emphasis on leading indicators and on what matters. In Fishner’s eyes, a quarterly review of the annual plan just isn’t enough. “It's hard to change renewal performance in the current quarter. A renewal happens or doesn't happen based on the past year of customer experience with our products and services. We need to track leading indicators that create a strong renewal rate — customer onboarding, account health, and implementation services usage,” he says. “For every lagging indicator, we need to have a set of leading indicators that we review on a weekly basis.”

Fishner says this level of weekly scrutiny also keeps HashiCorp on track to deliver on the goals that actually drive the business, instead of getting distracted by urgent, low-leverage escalations. “If a different leading indicator is acting up, there’s an impulse to take action on it. But if it’s not on the annual scorecard, then earlier in the year we agreed that we don't think that's very important for the health of the company — so it doesn't need to be something we focus on,” Fishner says.

Stay focused on what you decided was important earlier in the year — not on this week’s shiny distraction.

For the full annual planning template (and more on how a chief of staff can reach their full potential) read more on “Focus on Your First 10 Systems – This Chief of Staff Shares His Full Playbook”

#6: Recognize when it’s time to change course by setting “kill criteria” in advance.

After annual plans are finalized, the beginning of the new year pushes teams straight into heads-down execution mode. But founders need to be wary of the risks of sticking to their plans too closely, says Annie Duke, First Round’s Special Partner for Decision Science.

As a consultant and former poker pro, Duke has written several books about the science of making decisions. She’s also extensively studied the human bias toward resisting change, and in her latest book “Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away,” she analyzes why it’s so hard for us to drop something we’ve previously set our minds to.

“Once we’ve established the status quo, like the GTM strategy that we’re currently executing on, there’s a bias that makes it very hard for us to switch,” says Duke. “When we dump that go-to-market motion and try to develop something else, if that new plan doesn’t work out, there’s an asymmetry to how we process that regret. We feel it much more keenly when we start something new. So we'd prefer to make incremental changes, hoping we can still turn it around.”

In other words, we're much more tolerant of the bad outcomes that come from sticking to the plan than from switching to something new. The question becomes figuring out when it is time to pull the lever and change tracks — which is something many often struggle with.

Duke finds that most goal-setting frameworks exacerbate this tendency. “A woman was running the 2019 London marathon and she started experiencing pain in her legs around mile three. And then, at mile 8, her fibula snapped. And here's the amazing thing — she kept running. She finished the marathon on a broken leg,” she says. “This might sound kind of nutty. But four people in that 2019 London Marathon broke something and continued to the finish line. Just a quick Google search will tell you that stories like this are incredibly common,” she says.

The problem with goals is that once we set a finish line, they’re graded pass-fail. And we will barrel toward that finish line, come what may. The goal itself becomes a fixed object, even though the conditions have changed.

Founders fall into this trap as well. “If nobody's buying the product, and we clearly haven't achieved product-market fit and it doesn't look like it's on the horizon, we'll keep tinkering anyway. We ignore the signals that we’re off track,” says Duke.

Here’s her advice to overcome this tendency to stick to the goals we outlined at the beginning of the year, come what may: Get specific about the “unlesses.” “I'm going to run this marathon unless I break my leg in the middle of it — and then I'll stop. This seems silly, because, obviously, we think, if we break our leg we’ll stop,” she says. “But you're not going to stop once you're in the middle of it. When you’re actually in the situation, it’s hard to see it. When you’re in the middle of a losing sales deal, you continue to pursue it and insist that you can still win. So when we’re setting goals, we have to set those unlesses in advance, too.”

To get more specific: “There are all sorts of benchmarks that you can set for yourself of what you need to see happen within a quarter or two. Those benchmarks become what I call kill criteria — literally criteria for killing a project or changing your mind or cutting your losses. If you miss them, it means you’re going to quit,” she says. “For example, assembling criteria in advance can help you see if it’s not a deal worth pursuing actively or bringing it further into the funnel.”

Goals are great — as long as you have thought in advance about what would make it so that you wouldn’t pursue that goal anymore.

“Reviewing those criteria on a regular cadence with an outside advisor can help mitigate your tendency to say, ‘No, I know I can turn around. I can tweak the messaging or hire a new salesperson,’” says Duke. “This is the strategy that investor Ron Conway uses: ‘You're a brilliant person, I have no doubt you can turn around. But what does turning it around look like within what time?’ A simple way to develop kill criteria is with ‘states and dates. ‘If by (date), I have/haven’t (reached a particular state), I’ll quit.’”

Outside of setting criteria in advance, it’s also crucial to intentionally build this habit as the year progresses. We recommend setting a reminder to regularly revisit these questions from Duke to check in on your annual plan:

- Are these goals still the right goals to pursue, given what we’re trying to achieve?

- How are we going to find out as quickly as possible that the thing that we're doing isn't working?

- If I imagine it's six months from now and this project has failed, what were those early signals or leading indicators?

- Is this just hard, or is it hard and not worthwhile?

“When we look at success stories that were a long time in the making, there’s a temptation to say sticking to it is just good — full stop. But the problem is that the grit that allows us to power through will also get us to stick to things that aren’t worthwhile,” says Duke. “Success comes from sticking to the stuff that’s working and quitting the rest.”