There’s a mirage deceiving founders in the AI era: Mistaking speed for traction.

The allure of vibe-coding an MVP in a few minutes offers a tempting shortcut past the hard work of figuring out why you’re building something and how to build it best. The problem, the solution, the team — these are the core company-building jobs you can’t outsource. But many founders figure they can adjust them on the fly in favor of racing to market. Just as it’s easier than ever to ship a product in record time, it’s easier than ever to build a product no one wants and a company no one wants to join.

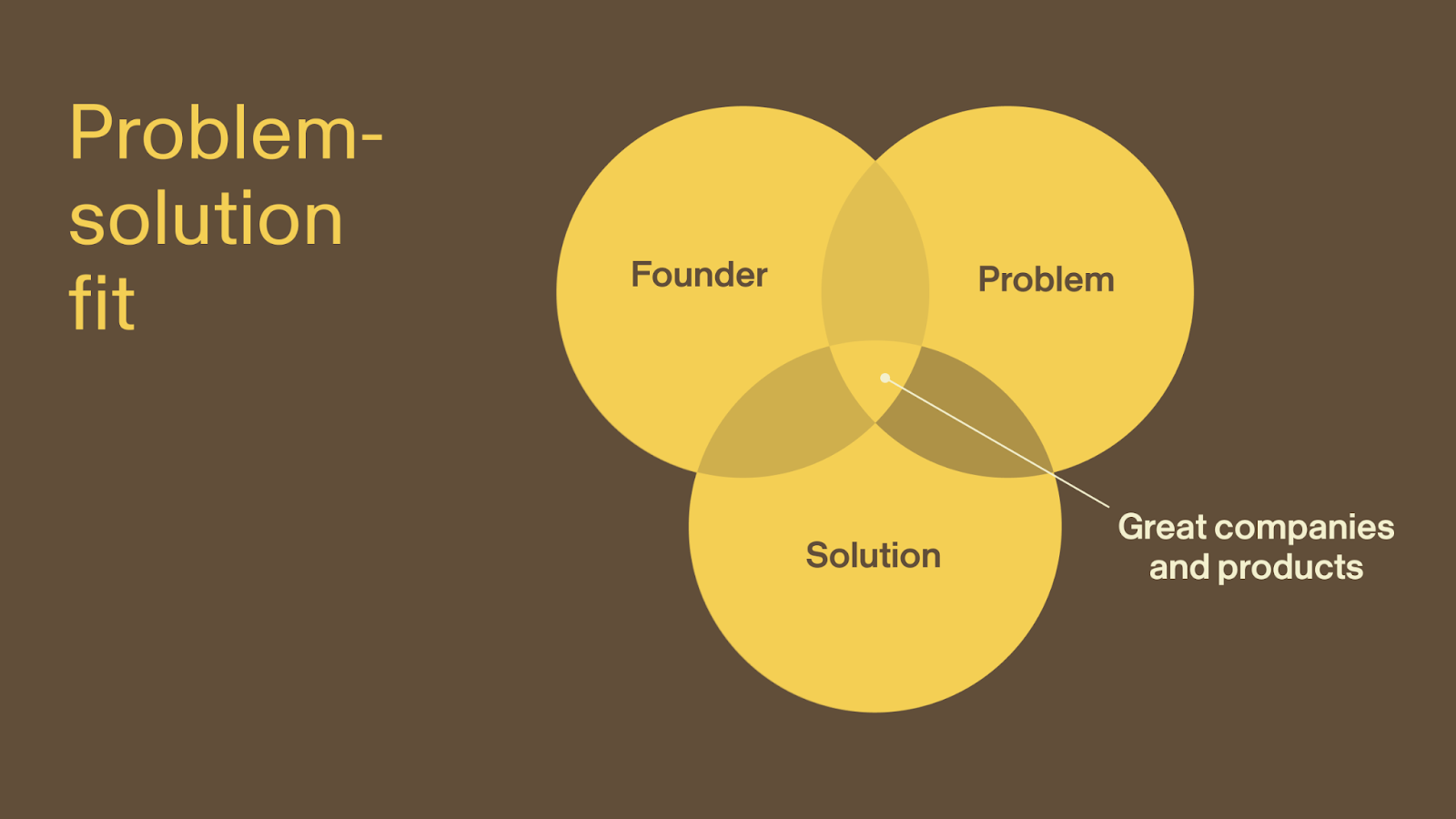

Jeanette Mellinger argues today’s founders are zooming past a step in their scramble for product-market fit: finding problem-solution fit, which includes the often-invisible yet critical component of founder fit. “Problem-solution fit means finding a deeper customer need that you’re uniquely positioned to solve, and building for it with better early signals and stronger team alignment from the start,” she says.

How? By taking a page from the UX research playbook.

Mellinger, a former Head of UX Research at Uber Eats and BetterUp, works with student founders as a Harvard Business School Executive Fellow and advises early-stage startups on all things research. She’s seen how a lack of diligence upfront leads to backtracking and double work, painful pivots and, ultimately, failure. So she wants to help founders add more rigor to their early ideation to build stronger foundations faster.

But you don’t have to sacrifice speed for depth. Think of it this way: Thoughtful upfront research helps train your intuition — so you can move faster and with more intention as you scale. “It’s even easier to speed in the wrong direction really fast with AI,” she says. “I want to help founders build velocity, which is speed in the right direction.”

Mellinger previously shared her detailed customer discovery framework with us, and now, she’s back with a research toolkit for finding stronger problem-solution fit, adapting her UX research and behavioral psych expertise for the founding journey.

“After working with dozens of founders and early-stage teams to uplevel their customer discovery skills, I’ve found that there’s still more work to do beyond solely focusing on the customer as they explore ideas,” she says. “The same tools that can help us get to know our customers can also help us do the essential but often unspoken work of self-discovery, which is just as crucial for building companies that last.”

In this exclusive interview, Mellinger starts by making the case for why finding problem-solution fit should predate selling — and even product building. She then breaks down the three phases of discovery, along with a comprehensive list of research methods and questions for three critical audiences: your customers, your team and yourself.

Whether you’re embarking on a blue-sky brainstorm, already in build mode or contemplating a pivot, she has the structure to help you pick your direction. Let’s dive in.

Why you need stronger problem-solution fit before you hit the market

Imagine a Bobo doll — the life-sized roly-poly toy with a round, heavy bottom. You can knock Bobo from any angle, and it will waver, but it won’t fall down. It stays balanced thanks to its weighted base.

“The components that make up problem-solution fit are your base as a team and company,” she says. “You take a week or a month to figure out your vision, your values and how you work. And when you’re lost, you come back to the foundation that you as a team or as a founder put together, so you can apply these principles to the latest thing you’re building.”

Mellinger is a fan of IDEO’s way of describing a good business: it’s desirable, it serves a human well, it’s economically viable and it’s something that you can technically deliver.

“When I joined Uber, I was part of the ‘Uber Everything’ group, which is what eventually turned into Uber Eats. The question we had to answer was, ‘What else could Uber do?’ And as I talked to people who’d been there for a long time, they’d say, ‘Oh, when we experimented with new businesses, they didn’t work. I see now they failed because they’d only gotten two of those three things,’” says Mellinger. “Usually the two that people focus on are the business case and technical feasibility.”

In recent years, startups have received the memo that the desirability component is make-or-break. But Mellinger has noticed that founders don’t always understand what building something people want actually entails. “Addressing sharp pain points is only one dimension. You can build something that’s ‘desirable’ but not really needed. Or if people can’t figure out how to use it, or the inertia of behavior change is too strong, then the product won’t go anywhere,” she points out.

Problem-solution fit is the intersection of who you are as a founder, a burning problem you’re well-suited to solve and a solution that tackles the problem well.

Finding this intersection isn’t a linear process. “Problem, solution and fit are all different steps, but you can't think about them in isolation from one another. You need to think about each one at every stage," says Mellinger. “And the silent first step is the founder. Before thinking about the problem, you've got to start with the founder.”

Here’s how Mellinger breaks down the goal of each overlapping circle:

- Founder: Understand how to assemble a connected, resilient team that knows what they’re uniquely suited to build and the conditions they need to do it.

- Problem: Deeply understand your target customers’ core needs, behaviors and workflows.

- Solution: Build a solution that’s differentiated, usable and easily integrated.

- Fit: This is the first level of product-market fit. "At the problem-solution fit stage, you should look for signs that the product you've built actually solves the problem your customer has,” says Mellinger. Refer to her customer discovery tools to help you assess fit.

Founders are constantly being told to change directions. You could run after your tail forever if you don’t have a center to come back to.

The three phases of deep research

Going through each of the steps to find problem-solution fit requires different levels of research. Mellinger says this will involve constant altitude shifting and changes of pace, inward reflection and in-depth conversations, blending methods from UX research, design and behavioral psych — techniques that aren’t often deployed in a startup setting, but that she’s found to be incredibly productive for founders.

Here’s a breakdown of her (handily alliterative) three phases of research.

Incubate: Fight the urge to build hurriedly to allow richer ideas to surface

There’s a reason the best ideas often arrive when you’re going for a walk, washing the dishes or taking a shower. “Incubation leans on what we know about where good ideas come from, along with UX research methods of observation and lighter secondary research. Look at how our brains work: Great ideas don’t happen on schedule. True insight takes time, and pops up in unexpected ways,” says Mellinger.

But that doesn’t mean bringing your discovery to a complete standstill. “Incubation is a conscious activity,” she says. “It just takes time and other associations to connect ideas in new ways.” A meta-analysis (a technique that draws conclusions from multiple studies) found that taking breaks — or incubating — can significantly improve creative performance. Another study that looked into the phenomenon of “hot streaks” across artistic and scientific careers found that the highest-impact work often follows seemingly unproductive periods.

So don’t even think about building anything in this phase. “When you move without ever stopping, it’s less likely that truly original ideas will emerge,” she says. “And there are some really lightweight ways to get to know a space and let these richer insights develop.” (More on those exact methods for incubation below.)

Immerse: Uncover more differentiated ideas and insights faster with focused sprints

This is where you’ll spend time exploring and codifying the most intriguing ideas from the incubation phase. “Immersion is about going deeper, not necessarily slower,” says Mellinger. “And it’s the perfect complement to incubation. In an ideal world, you toggle between both. Immersion helps you explore and codify quickly, but then also plants seeds for future ideas, kicking up even more incubation you can leverage later.”

Focus and depth will be more impactful than volume here. “I love the power of a really well-designed sprint. A focused week in the market with your customers can get you there faster than hundreds of disparate conversations with other customers,” she says.

‘I’ve spoken with hundreds of customers’ sounds sexier than, ‘I’ve had deep immersion with five.’ But you can get more out of an in-context immersion with five in a week or two than wandering conversations over months with dozens of customers.

Integrate: Build for behavior change (and be realistic about the power of inertia)

Integration means acting on the ideas you explored during immersion and incubation to plan how you'll build a solution that isn’t just differentiated, but easy to incorporate into a user’s life. Sounds simple enough from a product perspective. But getting humans to change their behavior is anything but.

Building a product is ultimately a human psychology problem. “Meaningful behavior change is required to get most products and processes off the ground, and it’s a lot harder than it seems,” says Mellinger.

The trick with this step is being realistic about — and deeply understanding — the hurdles you must overcome to get your customers to use your solution. “This is where you bring in tools to get to know humans. We know a lot about what motivates us through behavior change models, or in this case, asking someone to read your email or try your product — to do anything different.”

Behavioral research is a well to draw from here. Mellinger points to two behavior changes models to build on that work especially well in the product space:

- The Fogg behavior model. Stanford professor Dr. BJ Fogg created this simple formula that results in behavior change: B=MAP. Behavior happens when Motivation, Ability and a Prompt collide at the same time. Does your customer want to use your product, and is it easy for them to use it — and importantly, do they have a reason or reminder to start using it? If you fail to get your desired behavior, you’re probably missing one of these three things.

- The Hooked behavior model. Inertia is a powerful force, and building a product people want to use more than the thing they already use is an uphill battle. Nir Eyal, who conceived this model building on Fogg’s, says that a new product must be 9X better to escape the inertia of using the incumbent solution.

The integration phase is also a good time to study your incumbents. Inertia might explain why customers might be lukewarm about trying a new solution.

Building for behavior change has only gotten more challenging when practically every buyer and consumer is inundated with options. “You can come up with a great idea, but if you don’t honor the basics of behavior change, the product might not take off — because it wasn’t super easy to incorporate into their already-full lives,” says Mellinger.

Building something great doesn’t mean people will adopt it. There’s too much else going on.

And your research won’t be exclusively focused on your customers. You need to know and build around your own behavior. “You can apply the same skills for building a more behavior-centric product to make your work more motivating for you and your team,” she says. “For example, if you want to build a values-centered company, you can be smart about how you weave those values into both the product and your team’s incentives.”

Apply these methods to find problem-solution fit

So which methods can get you there? And how much time should you spend on this research?

“I'm not telling folks to take a year before you launch,” Mellinger says. “Doing research in a product context is a balance of the stakes, your resources and what you need to achieve. You can do so much in a focused week, month or quarter, depending on the clarity you want or the gaps you have to fill.”

She breaks down each component of finding a fit for the founding team, problem and solution. She applies the research phases of incubation, immersion and integration to each of these elements, providing the questions you should be asking yourself to kick off each phase of the journey, and the assets you and your team should aim to produce together.

Your three phases of research will look different at each step, alternating introspection with interviews, observation with sprints. Moving through a mix of structured exercises will help you dial up your confidence in choosing the right problem, solution and team. And you don’t have to use every single method listed here — take your pick based on where you want to go deeper.

Not sure where to start? Take Mellinger’s assessment to benchmark your startup’s problem-solution fit and figure out which research methods might be most impactful for you and your team.

Founder

The goal: Assemble a team that’s aligned, connected and resilient, and knows how and what it builds best.

You won’t ship your founding team, but you can still draw on Mellinger’s research methods to uncover the right problem this specific group should solve and the exact ways they’re best suited to do that. “If you don’t have a solid team, it’s harder to execute on your brilliant ideas well,” she says. “And it’s a missed opportunity if you don’t incorporate what you do uniquely and exceptionally well into your problem choice and solution.”

To kickstart incubation, and to get a sense of how well you know yourself as a leader or team, start by asking yourself one or more baseline questions.

Baseline questions to answer:

(Take ~5 minutes to 1 hour)

- Why do you want to work on this?

- Would you be willing to work on this with this founding team for more than 10 years? Why or why not?

- What can you not help but do or think about — even when your time is constrained?

- How do you build or lead best? What helps you be most effective? Stay focused? Sane? Keep going?

Mellinger says that the second question is a powerful one to ask yourself — and potentially incalculably time-saving if the answer is no. “I asked this to a friend who's trying to start a company. She chewed on it for a little bit and was like, ‘Absolutely not. I definitely don’t want to think about this topic that long.’ That alone got her to save who knows how much time down the road,” she says.

Incubate: Build awareness around your strengths and behavior as a founder by exploring your four “zones”

(Take ~1 hour to 1 month)

Take one day to one month of observations to map out the activities that you excel at and give you energy with the four zones framework.

“This exercise is derived from a book called The Big Leap,” says Mellinger. “There are four zones you can exist in, at work and in life: Genius, excellence, competence and incompetence. You want to think of these four zones as aspirational zones — meaning you might not yet be a genius, but you should aim to be a genius.”

And counterintuitively, this model recommends you remain squarely in your incompetence zone. “The stuff that you are naturally bad at and know that you dislike, you might as well stay incompetent,” she says. “I think you can get bitten by the things you’re good at, but aren’t energized by, so I like that there are different dimensions to these zones.”

Fill out this worksheet to discover yours. “What’s fun about this exercise is that you can either think about past jobs or your personal life today, or you can use it as an observational tool for a month,” says Mellinger.

Then go through your observations to pull out the values you lead with. Think about which problems you're best positioned to solve — the things you've noticed you already spend tons of time thinking about — and which customers and solutions make sense for you to immerse yourself with. “So for example, if you notice that you work best when you have a stable routine, maybe don't go after a customer base that involves extensive, frequent travel,” says Mellinger.

Immerse: Lead a one-day to one-week offsite with your team.

(Take ~1 day to 1 week)

Get together with your team — whether that’s just you and a co-founder or a handful of others to define your team core, aim and path.

Work together to fill out this reflection worksheet developed by Mellinger. “At the inception of your company, you and your teammates can take anywhere from one to three hours to go through and answer these questions. The idea is to codify who you are, what you want and how you’ll get there,” she says.

Mellinger also recommends adding in some incubation time after this immersion step. “It can be productive to answer some of these and maybe walk away for a day, or even a week, and then come back,” she says.

This can also be a moment to explore your fit with one another, as a team. You and your founding team can each fill out your zone or foundational reflection worksheets individually, then map how your zones overlap and where they might diverge. Discuss the benefits of these differences, and what else you might need to work around.

Integrate: Make your Fogg behavior change profile.

(Take ~1 hour to 1 day)

Drawing on the Fogg behavior model, you’ll build one for your team to clarify how you most effectively achieve your goals.

AI can help here. Mellinger recommends taking your answers to the zones and reflection worksheets and asking an AI tool to develop a Fogg behavior model for you and your team so you can start thinking about your behavior change goals.

The founder deliverable: A team foundation one-pager.

Once you’ve used these methods to explore your goals as a founding team, you can translate your learnings into the core building blocks that make up your team foundation.

To do this, reflect on what you learned individually and as a group. If you get stuck, you can even use AI as a lightweight thought partner to draft or reframe statements. For example, copy your notes into a chat tool and ask: “Can you synthesize this into a one-sentence mission?” or “Give me 3 alternative mission statements based on this input.”

These exercises help you distill seemingly complex reflections into building blocks that feel concrete and actionable:

Core: Who you are

- Values: What drives you and your team

- Tools: What each of you offer and how you work best (strengths, fuel, differentiators, motivators, working styles)

Aim: What you want

- Vision and mission: The world you want to create and why

- Goals: Short- and long-term aims

Path: How you’ll get there

- Roadmap & execution system: How you’ll align and follow through

You can then weave these building blocks into your team assets and practices, which you can use during such key activities like co-founder matching, fundraising, hiring and onboarding:

- Company charter: Codifies your team’s purpose and commitments

- Founder alignment snapshot: Clarifies where co-founders are aligned or diverging

- Team working style profile: Your “user manual” that captures how you best collaborate

- Individual career maps: Aligns personal growth with company growth

- Values-aligned hiring process: Ensures you bring in people who strengthen the culture you’re building

Problem

The goal: Build your customer foundation to unearth the deeper problem you want to solve and the customer behavior you have to design for.

Get clear about how you’ll structure your time with potential customers and synthesize what you’ve learned.

Baseline questions to answer:

- What’s your customer’s stated problem versus underlying need?

- How do they solve the problem today, if at all? What’s their workaround, and how much effort do they put into it?

- What unique insight do you have about your customers?

Incubate: Internalize customer problems and behavior through community observations.

(Take ~1 day to 1 month)

“It's your job to figure out where your customer spends time in person and online, and go there,” says Mellinger.

Spend time poring over the places your ICP hangs out, whether that’s in person or online. Subscribe to newsletters, lurk in online forums like Reddit and Discord and sign up for conferences where your customers will show up en masse. Listen to their favorite podcasts. Read their go-to publications. Take notes on patterns that start to emerge.

Mellinger shares an example of how incubation took shape for Uber Eats. “We’d order a ton of delivery, and even watched other people in our family or friend group do so. I’d order for a dinner party, and then I’d order for myself, and take note of how the experience is different,” she says.

Immerse: Spend time in customers’ worlds for one week or more.

(Take ~1 week, plus prep time)

Go physically where your customers are. Conduct an in-market research sprint to go deep on customer needs with in-depth interviews, ideally in the places where these folks spend time focused on the problem you seek to solve, so you can observe their behavior and pick up on details they might not think to mention.

Mellinger’s customer discovery article has robust guidance on how to get the most out of these interviews and keep bias at bay.

At Uber Eats, Mellinger says in-market sprints meant traveling onsite to launch a new product or learn about a new customer base, which included research in India, Colombia, Saudi Arabia, the UK, China and the US.

She recommends going to the physical location first, and then rounding out your immersion from your computer. “Use in-market sprints when you’re doing upfront problem and behavior discovery, and need to understand your customer’s worlds, workflows and broader goals,” she says. “After that, you can do more research sprints remotely, as you’ll already have an internalized sense of the context. Though it’s always helpful to have a balance of in-context and remote research sprints, to balance speed of answers with depth of understanding.”

Integrate: Build a behavior change profile for your customer.

(Take ~1 hour to 1 day)

Build your customer’s behavior change profile so you have a gameplan for how your product will leap over the hurdle of behavior change: What motivates them to try your product? To keep using it? What must be easy in order for them to do so? What will prompt them to start? To come back?

This process isn’t all that different from building a behavior change model for yourself — and can actually help you build empathy for the hurdles your customers must jump over to change their behavior.

Once again, Mellinger recommends leaning on AI tools to help translate the customer insights generated during the incubate and immerse phases into this profile.

You can also include questions during immersion, and conduct observations specifically tailored to answer these behavior-centric questions, including understanding customers’ process for attempting to solve the problem today, what prompted them to try this approach and how it’s changed over time.

The problem deliverable: A customer foundation.

As you close your first customer sprints, the goal isn’t just to collect insights but to distill them into a usable foundation. This means translating scattered interviews and observations into a clear picture of who your customers are, what they want, and how they try to get there today. These building blocks help ensure you’re not building in a vacuum but anchoring every product and strategy choice in the lived reality of your customers.

Core: Who they are

- Target customer type (your ICP definition): Who you’re focused on serving

- Core needs: What they consistently struggle with or aspire to

- Behaviors: Motivation, abilities, prompts

Aim: What they want

- Ideal state: The future they’re hoping to reach

- Goals: What success looks like for them

- Problems: What’s blocking them from progress

Path: How they get there

- Customer journey: Their steps with or without your product

- Competitors and workarounds: Who and what they rely on now

- Opportunities: Gaps and leverage points you can serve

You can then translate these building blocks into these sample deliverables that can be used to plan and improve your customer development, product ideation and refinement, team onboarding and fundraising narrative:

- In-depth ICP profile: A living document of your ideal customer’s needs, problems and behaviors

- Journey map x needs: A clear view of where customers get stuck and how they try to solve it today

- Founder–problem fit overview: Evidence that you’re personally well-positioned to tackle this problem

Solution

The goal: To build a product your customers are happy to change their behavior to use.

Baseline questions to answer:

- How does your solution fit customers’ needs?

- How does it fit into their lives or existing workflows?

- What makes your product more than 9X better than customers’ existing options?

- What unique experience or expertise is built into your product?

Incubate: Internalize product needs and best practices.

(Take ~1 day to 1 month)

Get to know incumbent solutions by doing a product trial. “Both in the physical and online worlds, try immersing yourself in a product area,” says Mellinger. “So actually use a product end to end yourself, over time, or watch other people use it in the wild.”

Beyond actually trying out an incumbent product, she also recommends scouring through product reviews to understand how customers talk and think about themselves.

Next, look for analogous inspiration from unrelated domains. This is where you completely exit the industry you’ve been doing research in and study how other products tackle experiences you want to create.

“Let's say that you want to create a product that’s gamified, even if you’re in the healthcare space. So you download Duolingo and learn Spanish for a little while just to get a feel for how the product gamifies the experience,” says Mellinger. “Or maybe you really want the experience of your product to be delightful and over-the top. Maybe that means you go to your favorite restaurant, or Disneyland, and see what you can learn from them.”

Immerse: Ideate and test a differentiated, usable product with a series of design sprints.

(Take ~1 day to 1 month)

Once you codify customer needs and behaviors, you can use these sprints to first brainstorm then evaluate your initial concepts – from high-level approach, to specific product features. But before you build too much, you need a signal that you’re on the right path.

To do so, conduct one to three design sprints, ideally back to back, to test your value prop and initial concepts. Mellinger recommends The Sprint Book for sprint templates and planning guidance on their structured 5-day process to rapidly move from problem to tested prototype.

Revisit your founder and team zones to brainstorm opportunities for overlap of founder and problem with your solution. “Before you're even testing something, think about how the solution you're building is unique to you and your team,” she says.

Integrate: Design your end-to-end product experience optimizing for behavior change.

(Take ~1 day to 1 week)

Uplevel your customers’ end-to-end product experience by building in behavior-centric levers at each key step, drawing from the Fogg and Hooked models.

Start by drawing out a journey map of your customer’s experience — follow their entire journey with the problem space, and then eventually zoom in to the interaction with your product. “The format doesn’t matter. Spreadsheets are just as good as sketches,” says Mellinger. “The goal is to externalize your thinking and capture the most important experiences for the following moments: awareness, consideration, purchase, first use, ongoing use, discontinued use and reuse.”

She lays out how the customer journey might shape up for Uber Eats. “The general journey is how customers make decisions about getting food,” she says. “Then you can zoom in on what it looks like to get food delivery. And from there, you map out the experience with your product, starting with initial product awareness into actually using it.”

Once this is mapped, overlay a behavior model on the most essential moments.

It’s your job to make sure you know your customers’ journeys inside and out.

The solution deliverable: A product foundation.

Once you’ve defined the problem and customer clearly, the next step is shaping your product response. A product foundation takes early ideas and translates them into principles, vision, and opportunities that will later guide what you build, when you build it and how you test along the way.

Core: Evergreen product components

- Design principles: Rules of thumb that anchor product choices in customer needs and behaviors

Aim: What the product can become

- Product vision: The future state your product is building toward

- Goals & metrics: What success looks like (Sample metrics might include usability, engagement, adoption, business outcomes)

Path: How you’ll get there

- Journey maps: How customers interact with your product across all touchpoints

- Opportunities now, next and later: How to define your focus on a timeline

- Experiments and concepts: Ways to test your solution quickly

Once you’ve started exploring how you’ll build for behavior change, draft your product plans into the following assets, which, just like the founder and problem deliverables, you can revisit during fundraising, customer development, product ideation and review and onboarding:

- Design principles: Guardrails for product teams to stay true to customer needs

- Product requirements document (PRD) components: The practical blueprint for turning vision into specs

- MVP opportunity map: Helps you prioritize what to test first

- Product roadmaps: Creates alignment around timing and focus

- Early value props and concepts: Lightweight prototypes and narratives that let you test resonance

If you’re at the very beginning of your founding journey and just starting to explore ideas, Mellinger recommends starting with these five methods:

Revisit this framework as you sell and scale

“Fit” isn’t a definitive endpoint. You’ll flip back and forth between incubation, immersion and integration as you explore different problems and solutions (and even teams).

This work isn’t the first and last time you’ll put on your UX researcher hat as a founder, either. Mellinger says this toolkit will serve you again and again at future inflection points, from launching new products to recalibrating the team as you grow to running a diagnostic on an underperforming feature.

The goal of this research framework is to help you think better as a founder, no matter where you are in your journey. “You’re learning how to generate deeper ideas, how to work on something lightly in the background, and recognize when it's time to set everything aside and go really deep on something. That will be valuable at every stage of a company,” she says.

If you take one thing from Mellinger’s problem-solution fit framework, it’s this: Take some time upfront to build a Bobo doll that can’t get knocked down. “My hope is that the output of this work is a foundation — a set of tools and eventual learnings — that you come back to all the time,” she says.