“‘There are two kinds of people who don’t experience painful emotions such as anxiety or disappointment, sadness, envy,’ writes psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar. ‘The psychopaths and the dead.’”

This is the last sentence of the preamble to Liz Fosslien and Mollie West Duffy’s new book, “Big Feelings: How to Be Okay When Things Are Not Okay.” You might recognize this duo already. In addition to previously sharing excellent advice right here on The Review, you may have picked up their bestselling book, “No Hard Feelings.” Fosslien also runs the popular @LizandMollie Instagram handle, home of those viral illustrations that always seem to be making the rounds on social media — and perfectly capturing the workplace anxiety so many have experienced in recent years.

After writing the book on embracing emotions and getting vulnerable at the office, Fosslien and Duffy found they still had plenty to share on the topic, thanks to their work leading corporate workshops, regularly interviewing folks from their online community — and facing down their own personal hurdles.

“Our first book, ‘No Hard Feelings,’ was informed by the challenges we faced in our work lives. But this time around, we had both come through really challenging experiences in our personal lives, from dealing with chronic pain issues and losing people we loved, to battling depression, all while trying to work. It was about navigating these really ‘big feelings’ ourselves and then ripping off the Band-Aid to talk about them with others,” says Fosslien (who heads up content and communications at Humu for her day job).

Of course, the last couple of years have created a real-world laboratory for studying the intersection of these emotions and the office. These “oversized” personal feelings — like despair, comparison, and anger — have been swirling around and spilling over into the workplace. Uncertainty has taken root in every corner of our lives, from health and politics, to the macro-economic environment and constantly shifting trends in the startup sphere. In other words, being okay when things are not okay is a tall order these days.

In this exclusive interview, Fosslien dives deeper into three of the weighty emotions they address in the book — but from the manager’s lens specifically. “In conversations with readers, I’ve noticed how managers are feeling particularly overwhelmed and exhausted,” she says.

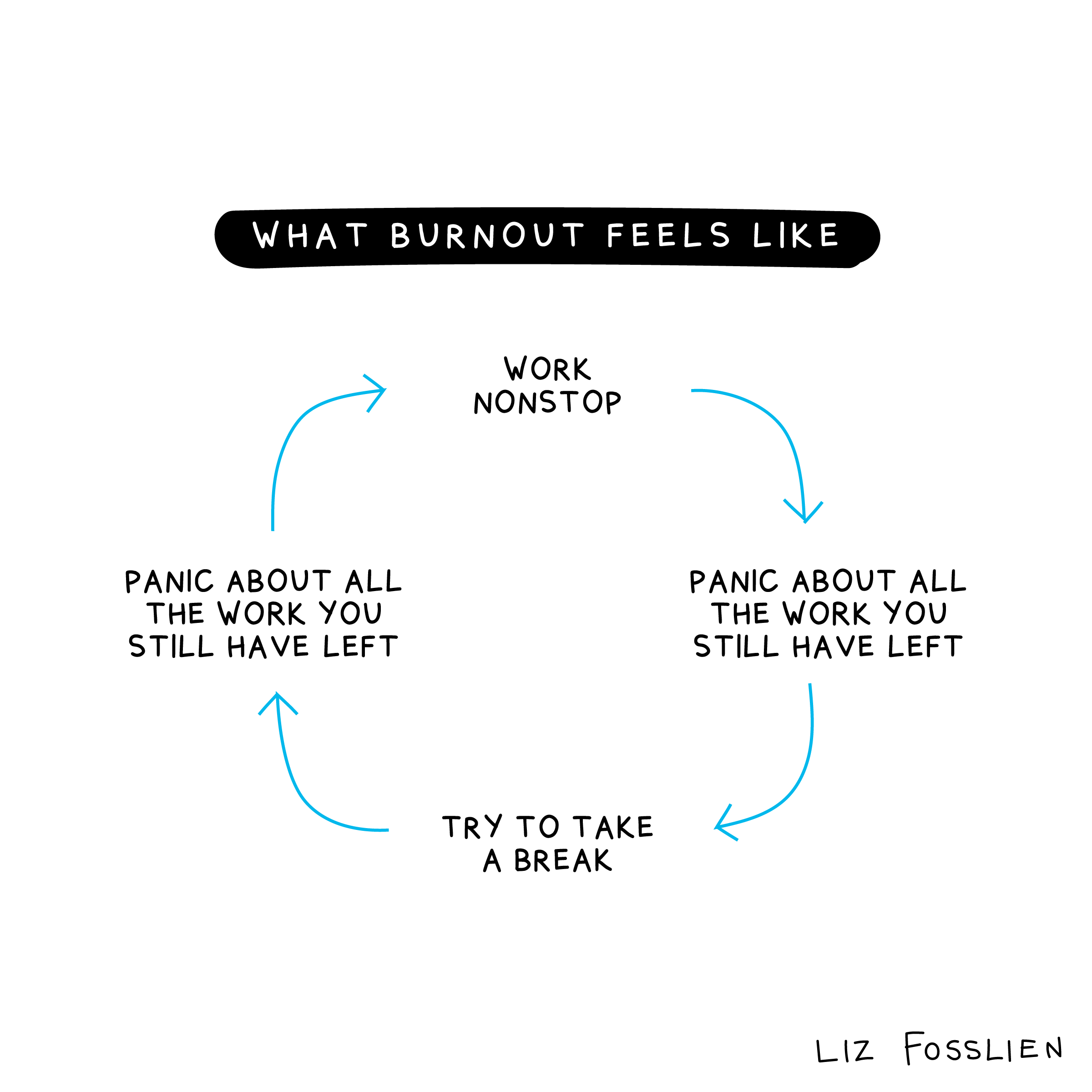

Many managers are struggling with what I call “burnout burnout” — providing emotional support and looking after the wellbeing of their team has become a bigger part of their roles in the last two years, and it’s starting to take a toll.

“Managers have had to shift their own style, handle tricky communications about return-to-office policies, and navigate cycles of hiring sprees and rounds of layoffs, all while keeping an eye out for company culture, checking in on how the team is holding up — and just personally trying to hang in there. After all, many managers are struggling with emotional and situational challenges themselves,” she says.

Read on for tactical, behavioral-science backed tips on how managers can help their teams (and themselves) wrestle with the pains of perfectionism, the burden of burnout, and the emotional upheaval of uncertainty. From common traps to avoid, to targeted questions to ask in your next 1:1, Fosslien shares actionable advice that leaders can use to steady the ship as we continue to plow ahead through unprecedented waters.

HOW TO CALIBRATE EMOTIONAL SUPPORT OF YOUR TEAM — AND AVOID COMMON TRAPS:

In addition to “burnout burnout,” there are several other boulders managers are struggling to shoulder. “Managers are sandwiched between leaders’ priorities and the immediate needs of their teams. Executives want managers to drive innovation and strategic initiatives, while managers are struggling to tread water with the basics,” says Fosslien.

“In our research at Humu, we found that managers reported that the greatest overall challenge has been balancing team member workloads and combating burnout (44%), followed closely by recruiting, hiring, and onboarding new members (41%) and keeping track of their team’s work (37%).”

Added to that mix is the pressure to stay poised. “Many managers feel like they have to keep it together 100% of the time, that they can never have a bad day. Especially if you’re a people leader, you’re going to have some rough days. That’s normal,” she says.

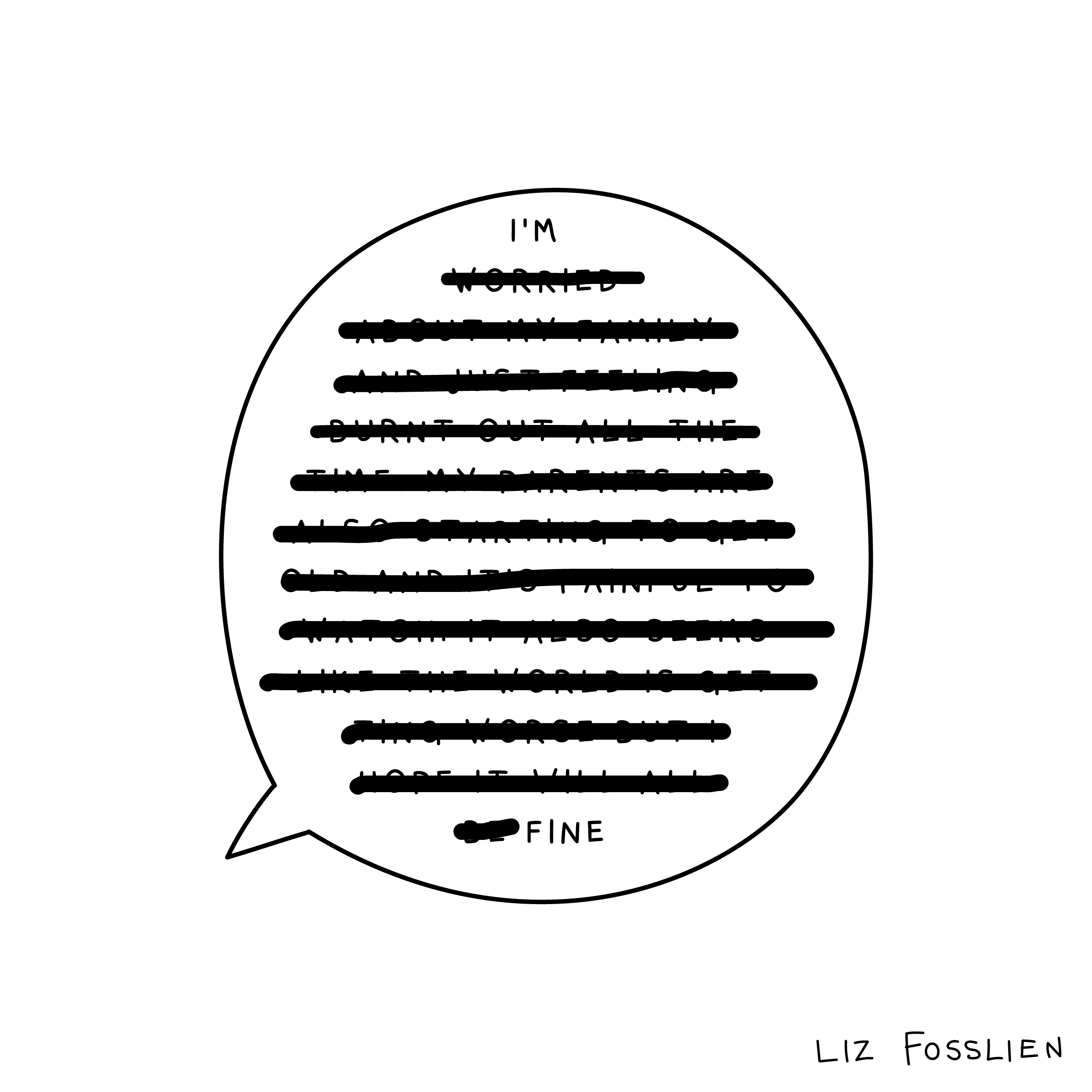

“I’ve struggled with this myself. In 2020, my father-in-law was losing his 10-year battle with cancer. Anyone who has had a loved one go through that can tell you it’s horrible. I was a mess but felt like I had to keep it together for my reports, especially since they were also going through hard times themselves,” she says.

“Instead of being open about what was going on, I purposely avoided personal conversations and would jump straight into agenda items, which was unusual for me. When I was finally forced to share what was happening — because I had to miss meetings for doctor’s appointments and eventually knew I was going to need to take bereavement leave — one of my reports said to me, ‘I’m so glad you shared, I could tell something was going on and was kind of worried about it.’ I wish I had opened up earlier, which likely would have reduced anxiety among my team.”

For managers facing similar struggles, Fosslien offers this piece of counsel: “You might say something like, ‘It’s been a day so if I seem distracted it has nothing to do with you.’ You don’t have to go into more detail, but acknowledging your feelings helps you avoid creating unnecessary angst.”

It’s the pretending like everything is fine that’s going to destabilize your team; people are much better at reading us than we think they are.

Fosslien shares five more specific traps managers are liable to fall into as they struggle to calibrate their own emotional loads:

- Getting emotionally leaky. Opening up doesn’t mean opening the floodgates, however. “Managers have to be more intentional about the emotions they express at work and about when to be transparent. Every time they are vulnerable, their reports are watching and analyzing their words and actions for a deeper meaning,” she says. “I’d encourage managers to practice ‘selective vulnerability,’ which is opening up to their teams while still prioritizing boundaries and stability. A simple formula is to pair a moment of vulnerability with a path forward. Something like, ‘I know this is a really hard time for all of us, I’m feeling it, too. My door is always open. Here are the steps I’m planning to take this month to ensure we’re balancing our well-being with making progress, and here’s what I need from you.’ You show you’re human but also that you’re still capable of confidently leading the team through a difficult period.”

- Assuming top performers are fine. “You might think that newer hires or people who are visibly struggling are the only employees who require your attention, but your top performers might need additional support, too. Make sure you’re regularly checking-in with everyone on your team,” says Fosslien.

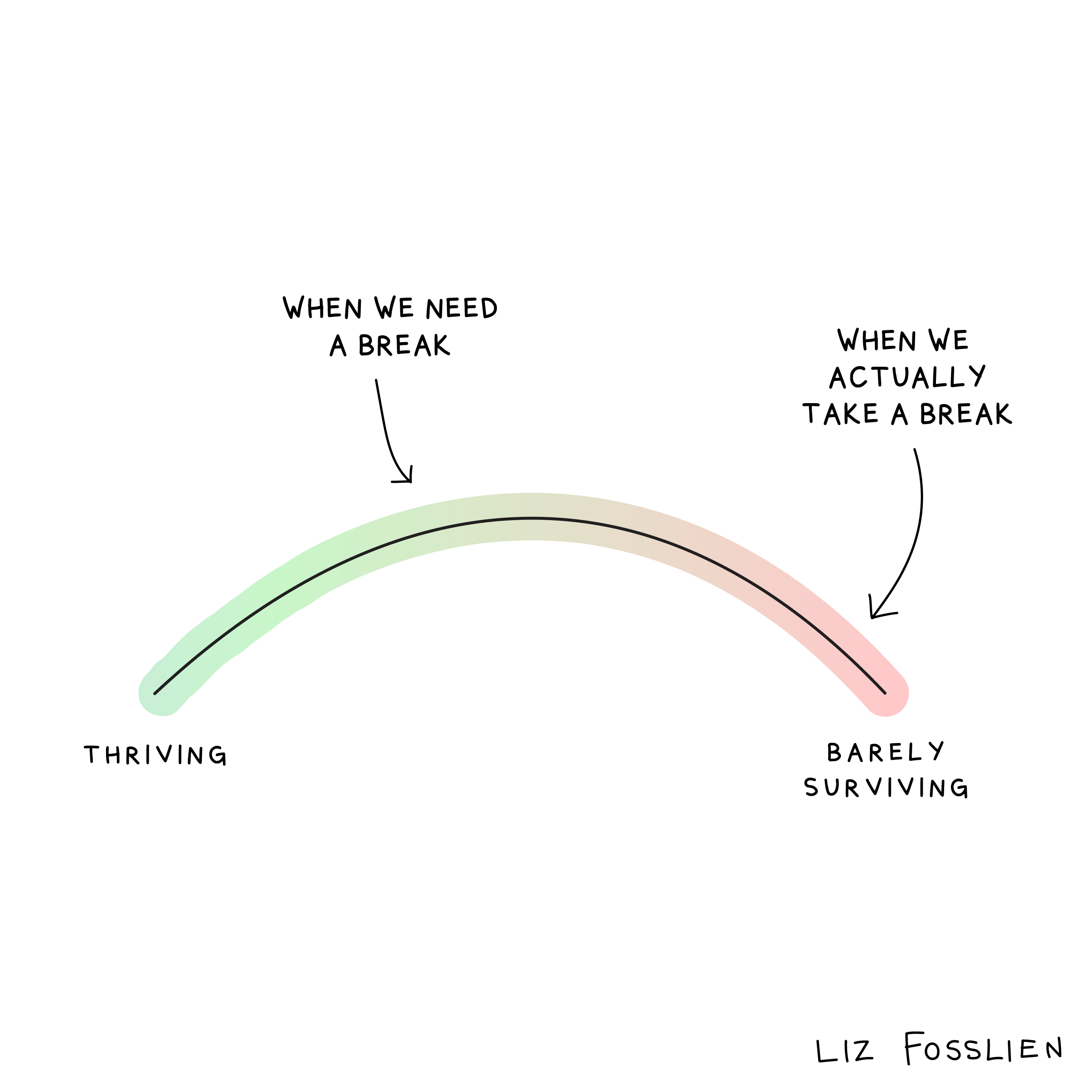

- Pretending at PTO. “Telling everyone else to take care of their mental health, but never taking a vacation yourself is a big one. Many managers admit to taking ‘Pretend Time Off,’ where they continue to chime in on email or Slack threads while purportedly on vacation,” says Fosslien. “If you’re a manager, you should regularly take vacation and sick days, making it clear that you won’t be available while away. This will help you protect your mental health and make it easier for your team to truly unplug on their days off, too.”

- Turning into a messaging monster. “When you’re under a lot of stress, or have too much on your plate, you’re more likely to hit send without doing what I call a quick emotional proofread. For example, firing off a note at 6 p.m. that says, ‘Let’s talk tomorrow,’ when in reality you mean, ‘Great presentation today; I have a couple comments I’d love to chat through tomorrow.’ That can ruin someone’s night. Pause and take a moment to think through how your actions and words might be received.”

- Neglecting the basics. “While it’s absolutely essential that managers be an emotionally supportive presence for their reports, it’s also important to prioritize the day in and day out work of leading: setting clear expectations, mapping out and communicating a compelling vision for the team, and ensuring that everyone feels a sense of continuous progress,” says Fosslien. “It may not seem like it, but these actions will also support wellbeing. Your people will feel better — and be more likely to take needed breaks — if they know they’re moving forward on the right things.”

HOW TO HELP YOUR TEAM WORK THROUGH UNCERTAINTY:

Every passing week seems to add to the feeling that we’re living through some truly turbulent times, whether it’s (another) uptick in COVID cases, a drop in the public markets, or upsetting events in the news, from global conflict to tragedies in our local communities.

“Psychologists who study stress have identified three primary factors that make us feel awful: a lack of control, unpredictability, and the perception that things are getting worse. In other words: uncertainty,” Fosslien and Duffy write in their book’s first chapter.

“Psychologist Dr. Molly Sands told us that we end up paying closer attention to everything that’s going on, because we’re not confident about what we should do, which is exhausting,” says Fosslien. “It’s also why you might start thinking, ‘I’m so overwhelmed, I can’t do this.’”

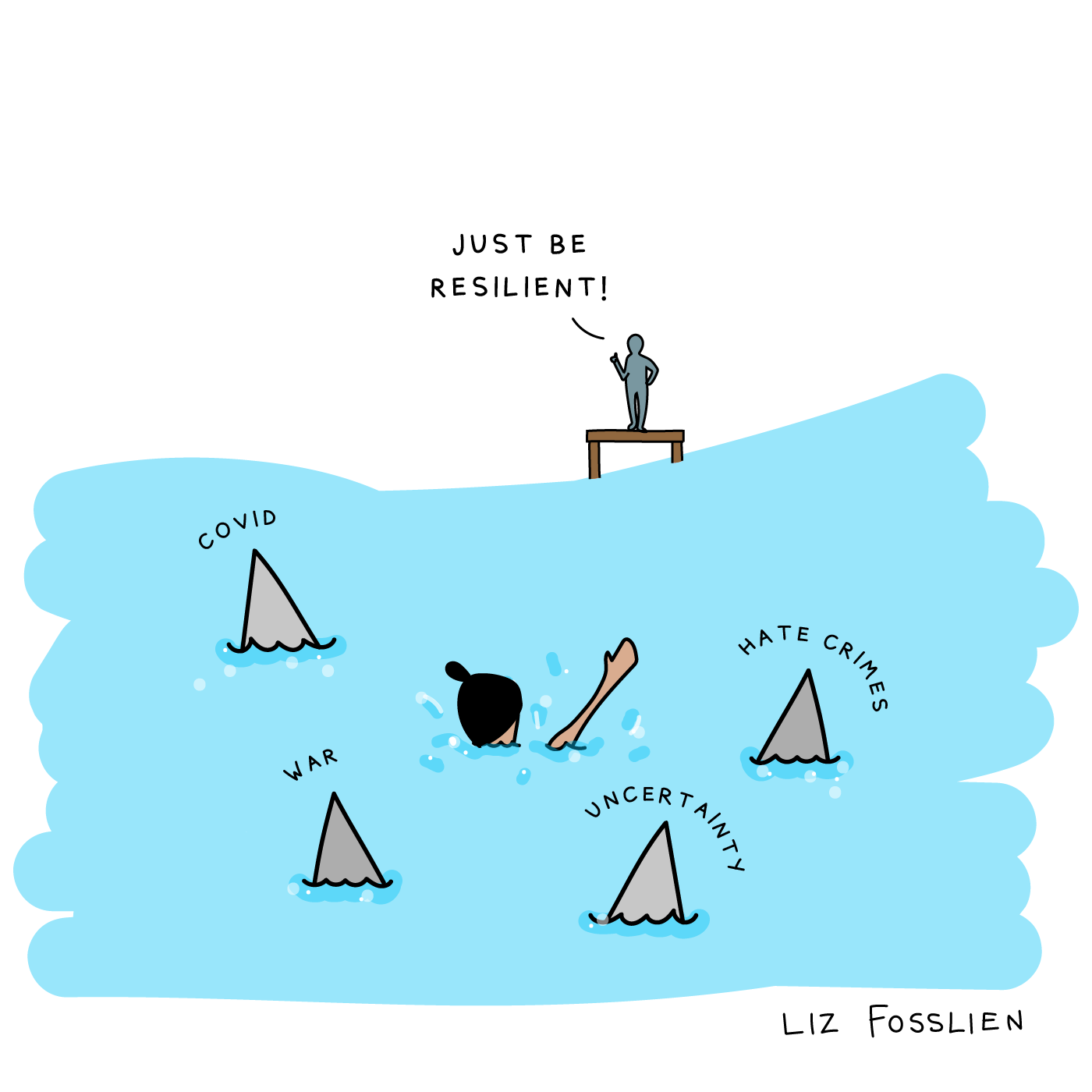

You’re probably familiar with one oft-suggested antidote to all this uncertainty. “Over the past few years, ‘resilience’ has popped up everywhere as the buzzword answer to everything. But change exhaustion isn’t an individual problem — it’s a collective issue that deserves to be tackled at the team or company level. We’re proponents of resilience — but not the kind that places blame on the individual or absolves leaders and institutions from their obligation to make structural improvements,” says Fosslien.

“The challenges of the past several years have been almost wholly out of your control as a manager. But how you choose to respond is not. You still have a role to play in whether your team is a place where your reports feel supported — or whether they feel pushed until their break points,” says Fosslien.

There’s a difference between demanding that everyone be mentally tough and helping them take care of their mental health. It’s much easier to be resilient in an environment that makes it easy.

Here’s a few specific ways managers can make uncertainty a bit easier:

Tip #1: Acknowledge what’s happening.

“When the news is filled with terrifying headlines, the most important thing you can do as a leader is to acknowledge what's happening. If you say nothing, your team will assume you either don't know or don't care about world events — which will erode trust. The racist mass shooting in Buffalo is a recent example here. It was particularly painful for the Black community, and many noticed a ‘business as usual’ failure to acknowledge it at work,” says Fosslien.

“Acknowledging a recent development can be as simple as sending your team a note that says, ‘In light of ______, I want to reiterate that if you need anything, please reach out. My priority is to support you.’ You can also say this during a team meeting. Chances are you don't know all the ways your people and their loved ones might be impacted, so team-wide notes can make sense,” she says. Fosslien shares additional pointers here:

- Check in individually depending on your team members’ situations. “For example, a friend of mine has a direct report based in Brooklyn. The day of the Brooklyn shooting, he made sure to check in with her and let her know she could take any time she needed,” says Fosslien. “Obviously you shouldn’t make assumptions about someone’s identity, but if they’ve shared something personal with you — like that they have family in Ukraine, for example — make it a priority to check-in when you know something has happened that might have directly impacted them.”

- Read the (virtual) room. “If you notice in a meeting that members of your team seem anxious or upset, acknowledging those feelings may help them feel less isolated. For example, if there’s been a particularly disturbing event in the news recently, you might say something like, ‘Let’s set the agenda aside for a moment. I know there’s a lot going on in the world. No pressure to share, but please reach out to me if I can offer you support, whether that’s helping you move meetings or pointing you to mental health resources or something else entirely. ’ You can also repeat this in 1:1s.”

- Don’t clam up. “Silence can be unsettling and lead people to assume the worst — even in the absence of new information or a clear way forward. Even if you’re not sure what’s going to happen next, or what policies might be rolled out, communicate that,” says Fosslien. “Say something like, ‘I know the leadership team is still figuring out our hybrid policy. I don’t have any updates yet but will let you know as soon as I have more information.’”

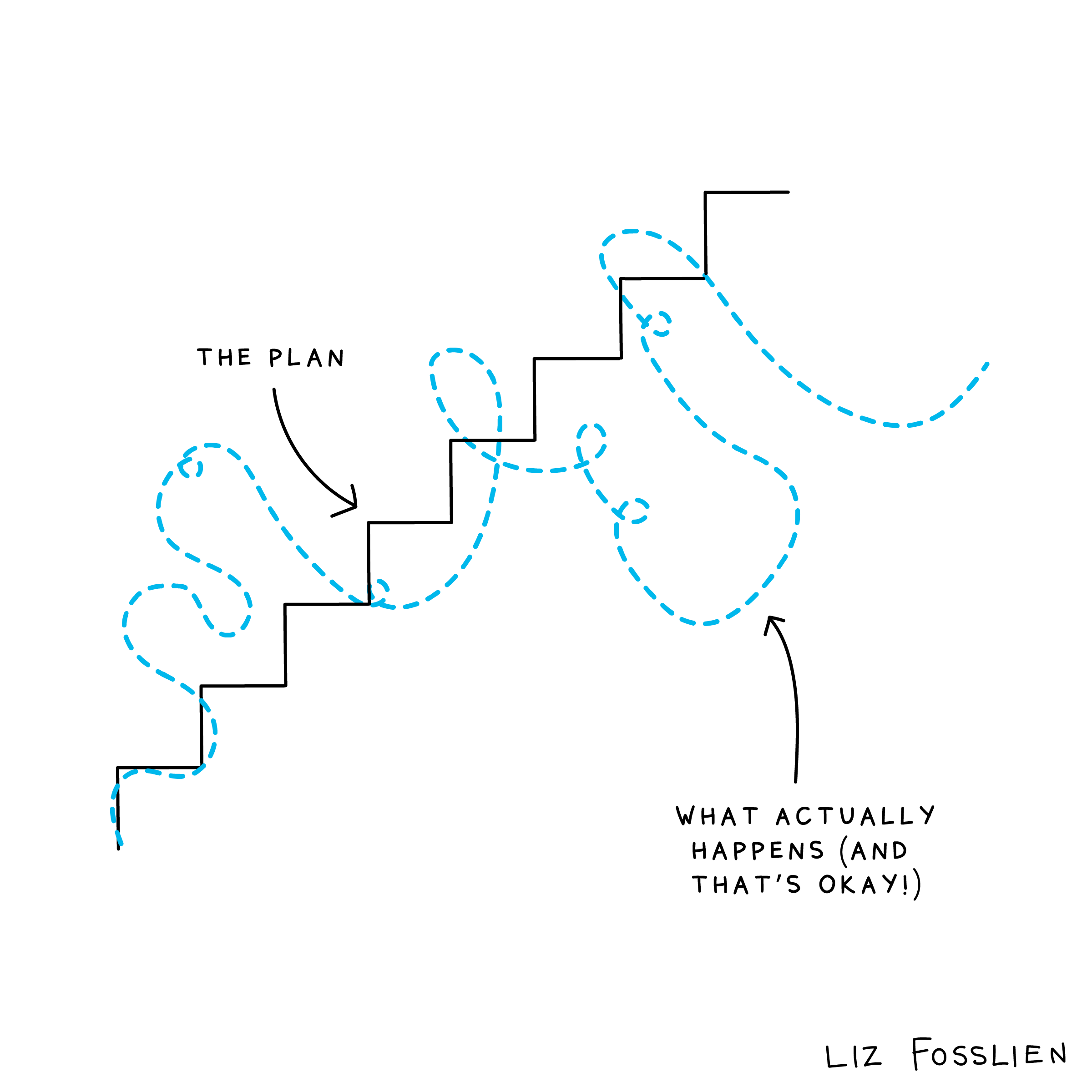

Tip #2: Make plans — from which you’ll deviate.

“For our book Big Feelings, my co-author Mollie and I interviewed Dr. Laura Gallaher, an organizational psychologist. She told us, ‘We don’t resist change. We resist loss.’ By converting ambient anxiety into more specific fears, you can pinpoint exactly what you’re afraid of losing and how you might be able to avoid some of those circumstances,” says Fosslien.

But in the face of uncertainty, it's easy to get swept up in analysis paralysis — and anxiously trying to plan for every possible future scenario is hardly helpful. “Dr. Laura Gallaher told us that teams at NASA have a practice called ‘making a plan from which you will deviate.’”

Here’s how it works: When the future seems uncertain, get together as a team to figure out the 2-3 most likely future scenarios and map out a few specific next steps for each one. Call these your, “Plans from which you’ll deviate.” “You shouldn’t see your plans as set in stone. The point of this exercise is mostly to reassure everyone that you’re prepared to face what comes next as a team. This can help the group feel more confident and informed, while also creating realistic expectations,” says Fosslien.

While you can’t accurately predict the future, you can increase your confidence that you’ll be able to get through whatever life throws at you. Successfully navigating change is not about trusting the world; it’s about trusting yourself.

Tip #3: Invest in collective rituals.

Part of enabling your team to be more resilient is supporting recovery time. “As a manager, you should ask yourself: How can my team better incorporate balance as a part of our days?” says Fosslien.

“When everything feels up in the air, rituals can help us ground ourselves. Studies show that habits can go a long way towards reducing our stress levels. In fact, psychologists have found that it doesn’t even matter what the ritual is — simply doing the same thing at the same time can improve your mental health,” she says. “This can make a big impact personally, whether it’s winding down with Wordle every night, or starting your day with the 7-minute workout. But making it a collective team practice can also be hugely effective.”

Fosslien shares several ideas she’s crowdsourced from teams:

- Kick off weekly team meetings with a fun prompt.

- Make a shared commitment to not schedule video calls with each other on one or two afternoons a week.

- Put 15-minute team breaks on the calendar every day.

- Give your team the first five minutes of a regular meeting to turn off their cameras and do something that will help them be more present, whether that’s responding to the email burning a hole in their inbox or getting up to stretch.

- Start a collective exercise designed to elicit what matters most to the team, whether that’s boosting energy, creativity, or connection. For example, try a daily 15-minute exercise where everyone shares something in Slack that is inspiring them.

The team is a helpful, and often overlooked, unit to reset together. On our own, we try to power through +8 hours with hopes of doing regenerative things like meditation or walks at the end of the day, but before we know it, we’re too exhausted and it’s too late.

HOW TO HELP YOUR TEAM PUSH BACK AGAINST PERFECTIONISM:

A team of perfectionists may not seem like such a bad thing. After all, attention to detail and constantly striving for results is likely on every hiring manager’s wishlist. But research suggests otherwise. “In 2005, psychologists Gordon Flett and Paul Hewitt set out to determine how perfectionism affects performance. They discovered that it makes a big difference, but not in the way you might expect,” Fosslien and Duffy write in their book.

“Looking at professional athletes, they found that people who displayed more perfectionist tendencies became overly concerned with their mistakes. Their fear of failure undermined their potential and made them do worse compared to their peers.” So if your own style as a manager (or the culture of your team) is closer to the perfectionist side of the spectrum, you’re likely leaving results on the table — and creative juice as well.

“In another experiment, researchers gave perfectionists and nonperfectionists specific goals. They also rigged the test so that everyone was doomed to fail. Guess which group quickly gave up? The perfectionists felt ashamed and tapped out early, while the not-so-perfect group kept plugging away, learning and having fun.”

By obsessing too much over getting it exactly right, we undermine our ability to succeed. The key to success is practice, which involves errors, failure, and asking questions — all things that perfectionists struggle with.

Fosslien offers up her advice for wrestling with these feelings and ensuring they don’t seep out onto your team, while still pushing for results:

Tip #1: Identify your style.

“Researchers identified three types of managers:

- The good enough manager, who sets clear goals but then lets employees figure out how to get there.

- The not good enough manager, who is all over the place or rarely checks in.

- The uber manager, who is a perfectionist with rigid standards for how every step of the process should be completed.

“When asked to pick which one they’d like to work for, most people picked the ‘good enough manager.’ If you’ve ever worked for a micromanager, that finding shouldn’t come as a surprise. Having someone oversee and nitpick every move you make can be a powerful motivator — to find another job,” says Fosslien.

Think through which of these might be your style, or you ask a colleague or friend for input. Here are some signals that you might be struggling with perfectionist tendencies as a manager:

- You find it hard to delegate and feel the urge to micromanage everything.

- You obsess over small details, which makes you lose sight of the bigger picture.

- You find it hard to be decisive.

- In 1:1s or team meetings, you rush straight into agenda items.

- Your feedback consists primarily of criticism, or you tend to focus primarily on what could be improved rather than what went well.

- You (explicitly or implicitly) don’t encourage experimentation.

“If you think you’re an uber manager, give your people more freedom than feels comfortable. Set clear milestones, but then step away and let your team members figure out how to get there. Make it clear you’re happy to answer questions or provide guidance, but that you won’t be involved every step of the way,” she says. “This will feel bad at first! But it’s a muscle you need to develop.”

Tip #2: Rightsize your expectations.

As you sort through your own tendencies and personal style, try to get curious about the expectations you’re setting — both for yourself and for your team.

“To begin charting a better course for yourself, write out your perfectionist thoughts and then reflect on these prompts,” says Fosslien:

- Where did I learn to set this expectation for myself?

- What is my perfectionism trying to protect me from?

- If I meet this expectation, will I actually be protected from what I fear?

And think through these questions as they apply to your interactions with your team:

- Am I praising effort, not just results?

- Am I sharing frequently enough about what I’ve learned from mistakes or situations that didn’t go as planned?

- Have I set reasonable expectations for each member of my team? “Be sure to ask your report to add anything they’re working on that isn’t on the list so you have a full sense of what they’re doing. Managers often don’t know everything that someone has on their plate, and then inadvertently assign them too much work,” she says.

Tip #3: Share your CV of failures

Here’s another sneaky factor that exacerbates perfectionism: “In 2010, Johannes Haushofer, today an associate professor of economics at Stockholm University, composed his ‘CV of Failures’ to help students realize that rejection is part of the path to success. It included sections like ‘Degree programs I did not get into’ and ‘Academic positions and fellowships I did not get,’” Duffy and Fosslien write in their book.

“Haushofer explains: ‘Most of what I try fails, but these failures are often invisible, while the successes are visible. I have noticed that this sometimes gives others the impression that most things work out for me. As a result, they are more likely to attribute their own failures to themselves.”

To combat a culture of perfectionism and constant comparison that holds people back, consider creating and sharing your own CV of failures, and encouraging others at your company to do the same.

Tip #4: Share at 80%

“I love the advice Dave Liss, a manager at Bleacher Report, shared with me. He encourages his teams (and himself) to share their work when they think it’s 80% there,” says Fosslien. “He said: ‘A project can often be deemed complete before its perfectionist creator feels it's really done. In fact, other people may not know the difference between 80% finished and 100% finished.’ In his experience, it’s also easier as a manager to help someone iterate on an 80% project than on something you consider 100%.”

Another tactic here is to have people share the research they’re doing in team meetings. “Experimentation is a really important part of innovation, but it often doesn’t generate tangible outputs so finding a way to bring visibility to what can become unseen work — especially in hybrid or remote environments — matters,” says Fosslien.

HOW TO HELP YOUR TEAM BEAT BURNOUT:

“Many think of burnout as if it’s solely related to how much we work — and that if we take time off, we’ll soon bounce back, born anew. But a vacation will not cure burnout,” Fosslien and Duffy write. “Burnout isn’t only about the hours you’re putting in. It’s also a function of the stories you tell yourself and how you approach what you do — in the office and at home. In fact, people who quit their jobs often find themselves, six months later, in a different role but feeling similarly depleted.”

Part of the issue is how burnout has become an umbrella term. “When we spoke with readers, they used it to mean they were tired, bored, fed up with their managers, overwhelmed by personal responsibilities, depressed, working too many hours — the list goes on and on. In other words, there are many shades of burnout,” they continue.

That’s why it’s useful on both an individual level and in your capacity as a manager to pinpoint exactly what you and members of your team are feeling — so you can get and provide the specific support that will be most helpful. Fosslien serves up specific tips on how managers can help triage here:

Tip #1: Look for the warning signs

“We’re quick to ignore these signs, because we can usually muscle through them. But they’re important alarm bells,” she says. Here are some of the subtle cues indicating that you (or your direct reports) might need to reassess how much you’re taking on:

- You feel so overwhelmed that you’ve started to cut out activities you know are good for you (such as exercise or alone time)

- You have the Sunday scaries — on Saturday.

- You’re saying yes even though you’re already at capacity.

- Getting sick and being forced to shut down for a bit sounds kind of nice.

- You’re all too familiar with “revenge bedtime procrastination,” when you stubbornly stay up late because you didn’t get any time to yourself during the day.

Tip #2: Show up (and start digging).

Simple, visible attempts to help your team invest in their wellbeing go a long way. “Our research at Humu shows that people whose manager makes an effort to help them combat burnout are 13X more likely to be satisfied with their manager,” says Fosslien.

Being an empathetic leader means fighting against your own biases, listening carefully to your reports, then using any privileges you have (by virtue of your leadership role or other factors) to take action on their behalf.

A key area is to make the most of 1:1s. “If your 1:1s focus solely on tasks, you’re missing out on a valuable opportunity to better understand and support your reports. Worse, you might be inadvertently sending the message that you care only about pressing to-dos, which can leave your team feeling expendable and anxious. Your job in 1:1s is to make each person feel heard,” says Fosslien.

“But that often means you’ll have to do a bit of detective work, as your reports may not be inclined to surface that they’re struggling,” she says. “You have to check-in in an authentic and meaningful way. Say one of your reports is an under-emoter. If she’s feeling overwhelmed, she won’t wear that emotion on her sleeve. She likely won’t bring it up in a 1:1 conversation on her own — and she won’t volunteer much to an overly broad ‘How can I help?’ question.”

Dig a bit deeper by asking questions like:

- What part of your job is keeping you up at night?

- What should I know about that I don’t know about?

- How does your workload feel right now?

- Is there anything I can take off your plate, help you delegate, or help you deprioritize?

- What one thing can I do to better support you? “The ‘one thing’ is critical here. It solicits more and better responses than a more generic ‘Is there anything I can do?’”

- What kind of flexibility do you need right now? “You could even give examples, like a doctor’s appointment, needing to turn your camera off, or dealing with a family issue.”

- Is anything unclear or blocking your work?

- What was a personal win this week, and what has been a challenge?

Also, be sure to close the loop. “If someone comes to you with a concern, suggestion, or request, always check back in with them,” says Fosslien. “Of course, you won’t always be able to implement an improvement based on what they’ve told you. But even simply saying, ‘Unfortunately I can’t take action right now because X, but I did look into it by doing Y and Z,’ goes a long way in making your people feel supported. If you never close the loop, your reports will get the message: ‘You don’t matter.’”

Tip #3: Set clear goals and spotlight progress

“When we don’t have clear goals, we either become stuck because we’re unsure where to invest our energy, or we frantically churn out a bunch of work in the hope that some of it will be valuable to the team,” says Fosslien. “At the beginning of every month, help each person on your team come up with five goals that connect to the team’s shared mission.”

It’s key to pair that goal-setting work with checking in regularly to make sure people feel a sense of progress. “One often overlooked facet of burnout is feeling stuck and like the effort you’re putting in isn’t getting you anywhere,” she says.

Try building a habit of taking stock of all that you've accomplished together by setting aside time at the end of each month to run through these questions as a group:

- What have we learned over the past few weeks?

- What was difficult, and how would we approach it differently given what we know now?

- What progress did we make?

Focusing on learning is critical, and it’s also a helpful tool for reframing negative self-talk. “When we tell ourselves, ‘We are a team that’s learning to ______,’ versus ‘We can’t do this’ or ‘We should have this all figured out already,’ we start to see ourselves as empowered agents of change.”

Look back at how far you’ve come as a team. We tend to burn out when we feel like the effort we’re putting in isn’t leading anywhere. Teams can sometimes be so future-focused that they forget to reflect on everything they’ve been able to achieve together.

Tip #4: Protect your team’s time — even when they won’t.

Above all, it’s crucial as a manager to be there in the moments when your people really need you. “A few days before my father-in-law died, he had a stroke that left him unable to sit up or speak. I was at his house helping out, and had a 1:1 with my manager. My manager opened the conversation, as she always does, by asking, ‘How are you doing?’ and I lost it. I had to turn my mic and camera off because I couldn’t stop sobbing,” says Fosslien.

“She immediately told me to log off and message her later in the day. When I finally collected myself and reached out, she told me in no uncertain terms that I wasn’t working for the rest of the week, and that I would be taking bereavement leave when the time came. To me, that’s what an amazing manager should do. During one of the most stressful times in my life, she made sure I didn’t have to gather the courage or energy to ask for help. She simply ensured that I had the support I obviously needed.”

But this work doesn’t arise just around life’s most challenging moments. Look for ways you can be there for your team on a weekly and monthly basis. “For example, how can you protect their vacation time? When one of my reports takes time off, I do everything I can to give them a real break. Sometimes that means reprioritizing projects, or me jumping in to finish something up while they’re out. I also don’t send them anything while they’re out,” she says.

Saying you want your people to have a healthy work-life balance is great, but if their calendars are filled with back-to-back meetings and they get pinged at all hours of the day, chances are they won’t feel safe taking the breaks they need.

Also remind your team that it’s not just about that vacation, but rather cultivating a daily practice of taking care of ourselves — and each other. “We often think that, as a reward for working, we get to take vacation, take breaks, and take care of ourselves, but consider the opposite — your health is what allows you to do meaningful work. Your wellbeing is the foundation for everything else in your life. This is easy to see on an extreme level — if you are having migraines so bad that you can only lie in bed and close your eyes, it’s impossible to work — but it is also true on an everyday scale. If you have overworked yourself, consider what you can change in your daily and weekly routines to find your way back into balance.”

Cover image by Getty Images / Roc Canals. Illustrations by Liz Fosslien. Photo of Liz by Bonnie Rae Mills.