This article is by Dave Girouard, CEO of AI lending platform Upstart, and former President of Google Apps. He’s known for leading the business now called Google Cloud through its first billion in revenue. Girouard previously wrote for the Review on why the best startups make speed a habit — here he shares his tips for adding effective writing to your founder’s toolkit.

"The pen is mightier than the sword," Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1839.

Of the many skills attributed to successful entrepreneurs — vision, execution, persuasion, perseverance, grit, resilience — effective writing inevitably fails to make the list. Yet I submit that the quality of your writing contributes to the outcomes you experience as a founder and executive day in and day out. Moreover, modeling and stressing the importance of effective writing throughout your organization can meaningfully improve business execution and outcomes on a broader scale.

Words matter. At a minimum, they shape the impression you make on others — often the first impression. Poor writing can harm you in so many ways: logic is hidden, points are lost, news is buried, intent is misread, feelings are hurt, credibility suffers. And that assumes anybody actually reads what you wrote.

But there’s upside as well. As any hack World War II historian knows, Winston Churchill famously bolstered the resistance of the English people during the darkest days of 1940, entirely through power of the written word. If a few well-crafted speeches shaped the outcome of the greatest military conflict in history, one might assume that effective writing can be a difference-maker for each of us.

Closer to home, I’ve witnessed how well-chosen words can alter the troubled paths on which executives find themselves. In my early days at Google, Sheryl Sandberg led a rapidly-growing operations team that was chronically deprioritized from an engineering perspective, resulting in exponential growth of manual work for her teams. Realizing that Larry and Sergey valued engineering-oriented efficiency and keeping Google “lean and mean,” she penned a famous document called “How not to hire 10,000 people,” making the case for investing engineering resources in her operations. Sure enough, Larry and Sergey soon let Sheryl hire as many engineers as she wanted.

Crafting Churchillian prose is beyond the reach of most and isn’t likely to land you the Sequoia term sheet. Yet, writing ranks as perhaps the highest-leveraged tool available to leaders of all stripes. Logically, the bigger your company becomes, the more writing is a skill worth having. Even in a world filled with weekly TGIF meetings Zoom-ed around the world, a few carefully-crafted paragraphs can often win the day.

Words and software share a wonderful attribute: Write them once and they can benefit an infinite audience at no additional expense.

MY HISTORY WITH WRITING

As a freshman at Dartmouth in the fall of 1984, I enrolled in English 5, a course designed to teach the fundamentals of writing while simultaneously dropping you head-first-with-hands-tied behind-your-back into John Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” I did not choose this — the course was required, unless one demonstrated writing proficiency via the English portion of the SAT. I did not.

Professor Spengemann demanded that his students write a weekly essay about “Paradise Lost” while obeying a set of structural rules with military precision. The hope was that, forced to write within the confines of a suffocating grammatical box, we would develop lifelong writing discipline even when those constraints were relaxed. English 5 became Dartmouth’s version of running on the beach in army boots.

Writing essays about "Paradise Lost" is enough to drive most 18 year olds to irresponsible levels of alcohol consumption, including this one. Yet decades later, English 5 with Professor Spengemann stands as the most enduring classroom experience of my life. If I can vividly recall writing lessons from three and a half decades ago, perhaps they might offer something of value to founders and executives looking to add something useful to their toolkit. The following are a few of the more memorable lessons learned in those cramped quarters of Sanborn Hall, blended with some practical writing advice I’ve inherited since.

DO AS I SAY, NOT AS I DO

I’m compelled to begin with two caveats:

First, I don’t claim to be a great writer. That swooshing sound you hear is this engineering major ducking for cover as more qualified wordsmiths evaluate my prose. I expect to violate many of my own rules in this very essay — after all, they’re actually guidelines more than rules.

Second, all writing doesn’t warrant the same care. Texting, direct messages, Snapchat and the like have taken on a life of their own, giving birth to a crufty, if not functional, derivative of the English language. Even good ol’ fashion emails aren’t always worth the time to reach for your editor’s monocle. Sending in your lunch order? Feel free to reverse a couple letters or come up short on punctuation. Update to the board? Let’s run that one through the spellchecker. But overall, I’d posit that most of us sorely underinvest our time in written communication.

Thus caveated, I give you the following eight pills of advice to improve your writing:

1. Use short, simple words.

Whomever convinced the world that fancy words make for quality writing did us a grave disservice. Particularly in business communications, simpler is better.

The Gunning Fog Index measures the readability of your text by counting words-per-sentence and syllables-per-word. The output of the GFI can be interpreted as the age at which your reader could have left formal education yet still understand your writing.

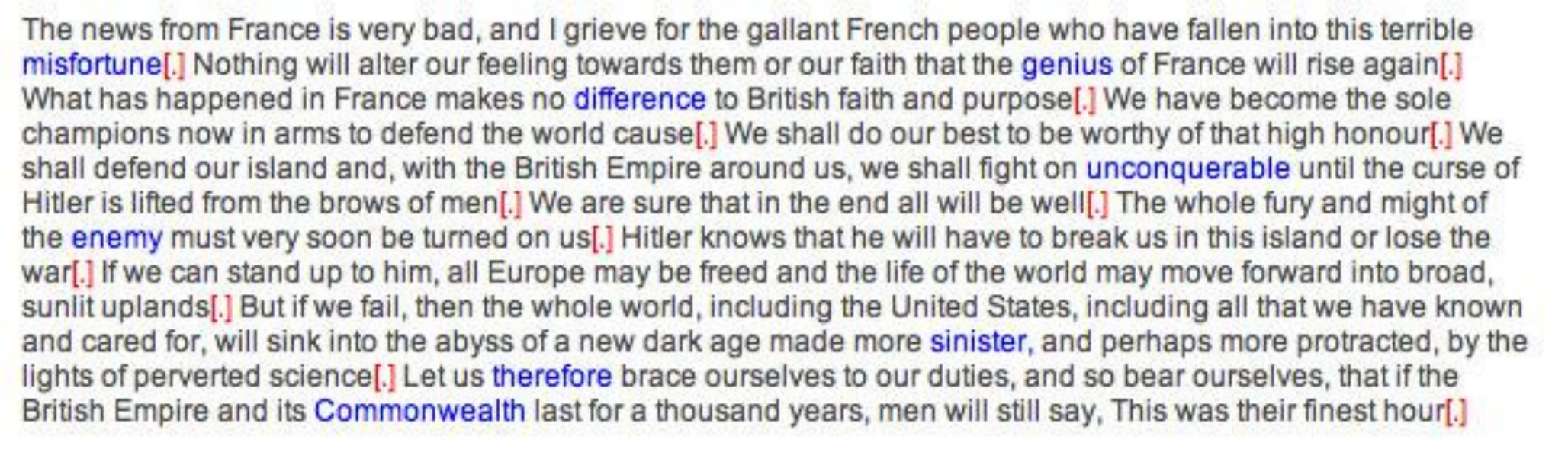

I often think of this passage by Churchill, as highlighted in a blog post I read years ago (words of three or more syllables are in blue.) The GFI is 9.8 years — meaning your average 5th grader could understand Sir Winston’s speech.

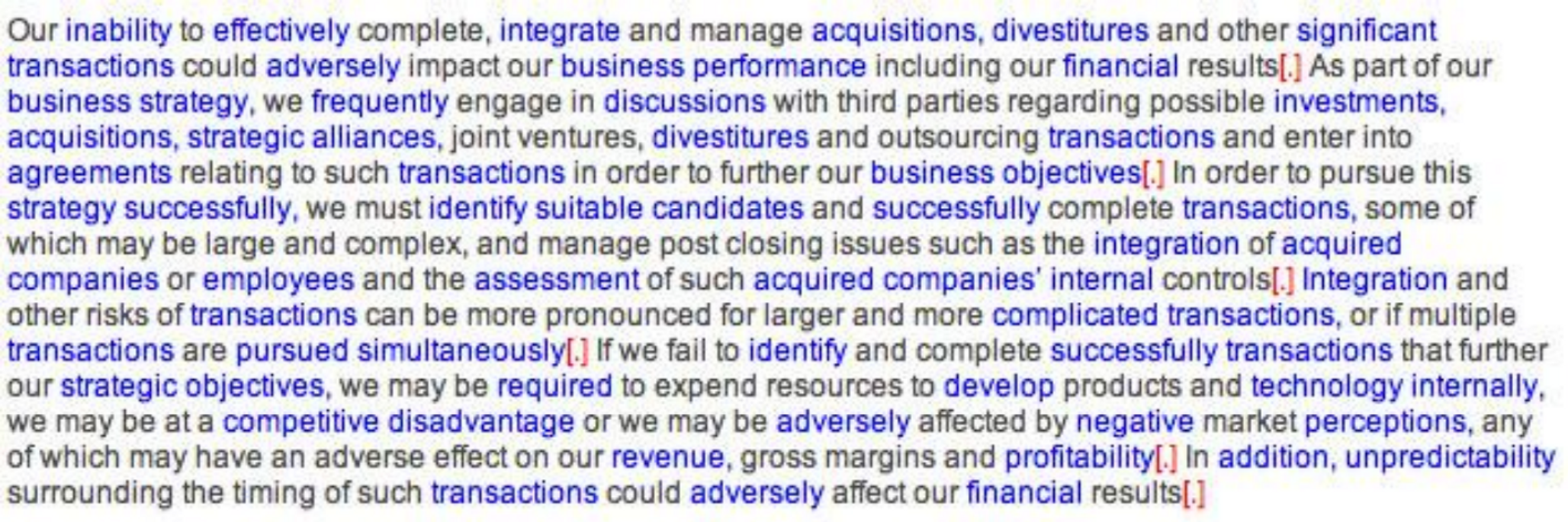

Now stomach, if you can, this gripping prose from a Kodak SEC filing. The GFI is 25.7 years, suggesting a Masters degree may be a prerequisite to making sense of this mess:

When landing your message really matters, aim for the “pie-eyed, mouth-ajar” response that Sir Winston’s speech elicits, rather than the lazy scan-and-snooze reaction brought on by Kodak.

But how to get it done? A search-and-destroy mission for business jargon is a fine place to start. Why “divest” when you can “sell”? Why pursue “business objectives” when “goals” can get you to that promised place?

If you do nothing more than write each day as if your audience is a well-read middle schooler, you’ve outdistanced the crowd by several steps.

2. Let your verbs do the work.

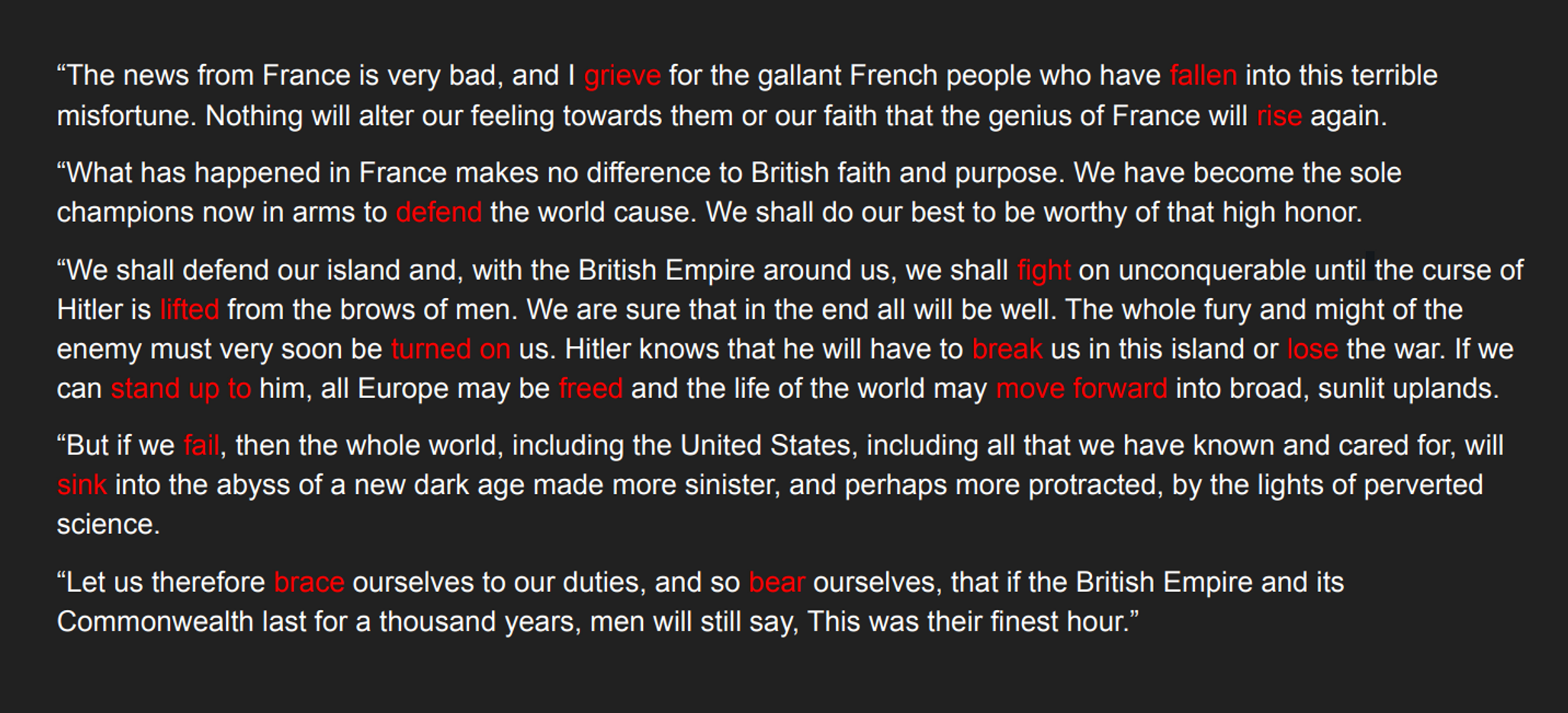

Effective writing leans heavily on verbs and less so on adjectives and adverbs. Look again at this Churchill speech.

Known for delivering harsh truths somehow juxtaposed with dogged optimism, Churchill’s choice of verbs leaves little doubt as to the seriousness of the situation: grieve, fallen, defend, fight, break, lose, fail, sink, brace, bear.

Choosing those words undoubtedly required careful thought and rigorous editing (the author was likely dictating from the bathtub). Yet most of us opt for the first verb that pops into our head, before larding up our sentences with junk filler until we’re satisfied the point has been made.

Invest time and energy in the verbs and your writing will improve.

In Professor Spengemann’s class, we were not allowed to use the verb “to be” (is, am, are, was, were) — ever. These laziest of verbs provide an escape hatch to writers while communicating nothing more significant than the equal sign. While syntactically correct and downright helpful, the verb “to be” was verboten in Sanborn Hall in September 1984.

For five and half years, I’ve religiously crafted a monthly email update for Upstart’s Board of Directors. With echoes of Professor Spengemann in my head, I regularly swap out lightweight volleys such as “Last month was a difficult one,” for sniper-like direct hits like, “Business tanked last month.” Fortunately, the news is rarely that disappointing, but when it is, my board members can expect to receive it sans-sugar.

3. Eliminate a̶l̶l̶ unnecessary words.

“If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.”

This quote (the origin of which is subject to significant debate) sums it up well. Sadly, writing concise sentences takes time and effort. As a first step, consider these tips:

- Turf the egregious filler words: very, rather, little, indeed, somewhat, really, kind of. These nutrition-free calories of the mind either cushion your weakly-held beliefs or lamely pretend to quantify something you’ve failed to quantify.

- As a general rule, if you can’t identify what part of speech a word is, best not to use it.

- You can leave out “I think”— your reader appreciates that you necessarily thought of this gem before typing it.

Clutter happens not just at the word level, but with sentences and paragraphs as well — what you might call the idea level. If extraneous words drain your reader’s attention, extraneous ideas can lead them to an “Alice in Wonderland” trip through your consciousness. While entertaining, these side trips may prevent your reader from mentally tracking your intended path.

Words fight for your reader’s scarce attention. Thus every unnecessary word detracts from the important ones.

Two simple tactics can train you to eliminate unnecessary ideas. First, knowing that humans excel at reading no more than absolutely necessary, consider which parts of your prose your reader will skip. Then delete them.

Second, walk away from your writing. Time permitting, do something else — get some exercise, enjoy a meal, or take a nap. When you return to your words, you’ll have taken a small step away from your bias as the writer, and a giant leap toward seeing your work through the eye of the reader. By the time I reach the final version, I’ve typically cut the word count by at least 30 percent.

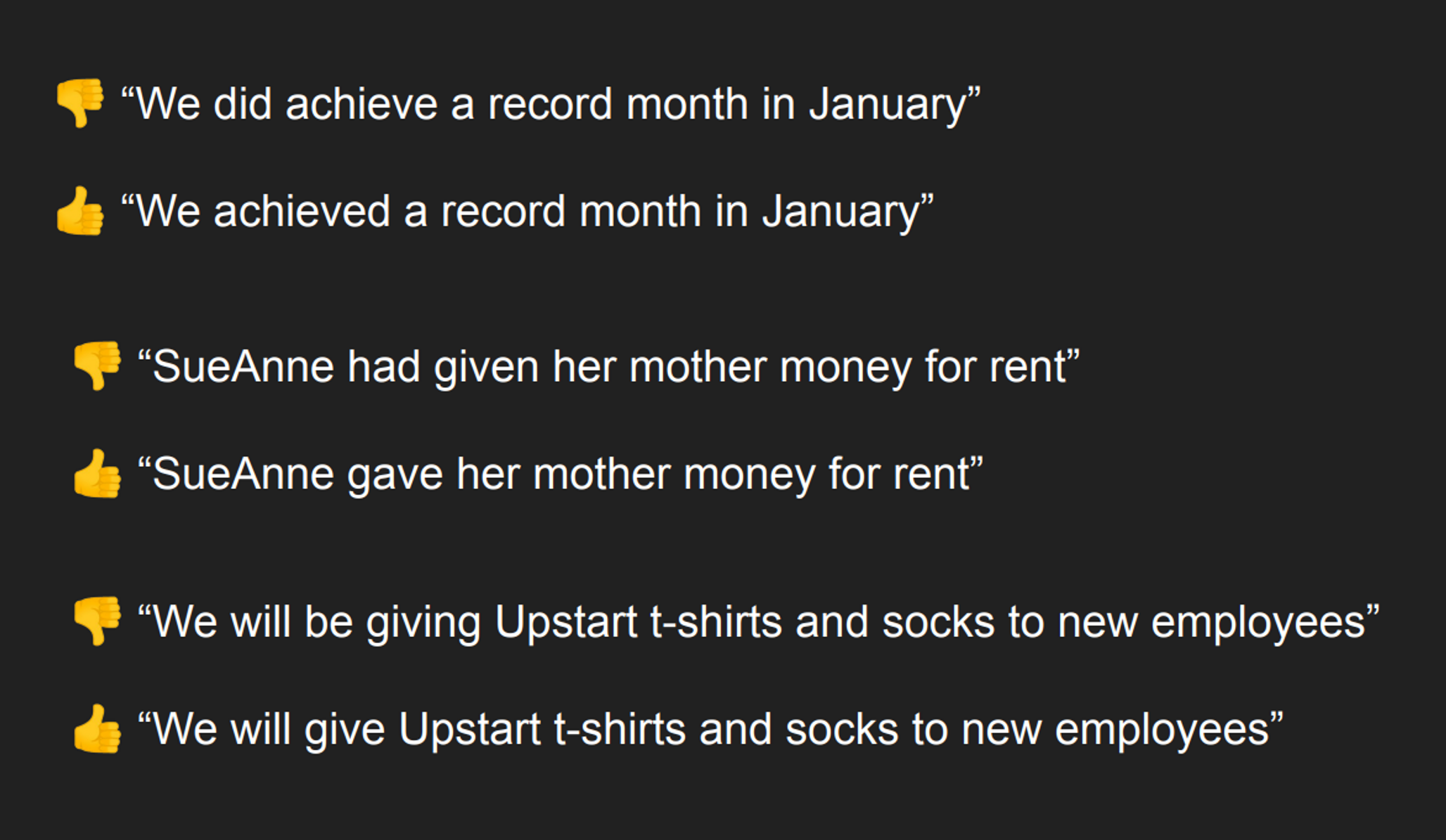

4. Use simple verb tenses.

The English language is blessed and cursed with a bounty of verb tenses. Twelve, to be specific: Present Simple, Present Continuous, Present Perfect Simple, Present Perfect Continuous, Past Simple, Past Continuous, Past Perfect Simple, Past Perfect Continuous, Future Simple, Future Continuous, Future Perfect Simple, Future Perfect Continuous.

Perhaps Professor Spengemann knows what they all do, but I don’t. Yet I can unequivocally state that writers too often choose the complicated forms when the simple ones get the job done.

I trust there are compelling reasons for each of our twelve verb tenses, and I’m confident there are talented writers who capably make use of each. Just tread carefully if you’re not one of them.

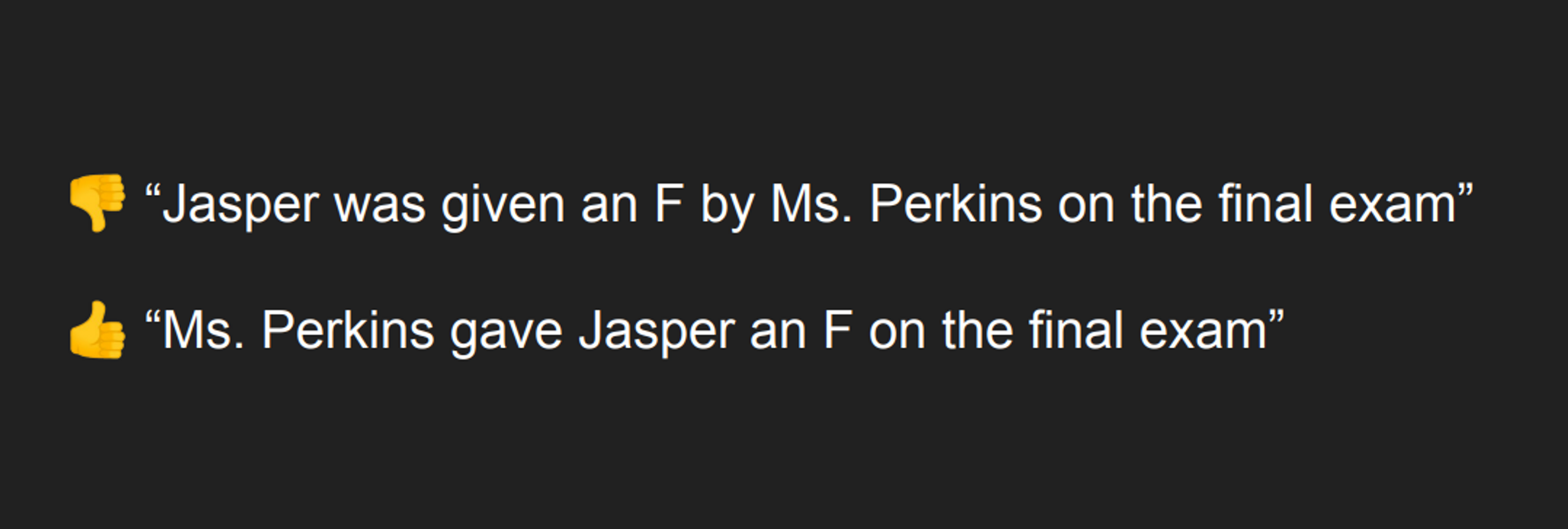

5. Avoid the passive tense.

If you’re thinking “Oh, verbs again,” remember that they are worth getting right. Without verbs, our language loses much of its pizazz.

Anyway, if banning the verb “to be” weren’t enough, the other army boot Professor Spengemann strapped on our feet was an unwavering commitment to the active tense. For those unfamiliar, the active tense implies that the noun at the beginning of your sentence is doing the doing. In the passive tense, the noun doesn’t do a thing — in fact the deed is done TO it.

These many years later, I see now why the good professor viewed the passive tense with such disdain. To my ear, it sounds, well...passive. Indirect and watery. A leisurely stroll around the matter at hand.

Conspiracy theorists might fairly suggest the passive tense often attempts to hide who exactly did the doing (“Statements were made calling Bill’s judgement into question”). In any case, opt for the active tense when you can.

6. Structure matters.

In the demanding world of Professor Spengemann, crafting concise and efficient sentences with acceptable verb forms was mere table stakes. Avoiding the wrath of the red pen required strict adherence to structured composition at multiple levels. Exceptions were not granted.

- The Paragraph: Once we were capable of constructing a water-tight sentence, next up was the paragraph. The first sentence should summarize the entire paragraph. The remaining sentences should support the first. Thus constructed, each paragraph articulates and defends a single idea to the last word.

- The Essay: From there, Professor Spengemann demanded that the essay in entirety maintained this rigorous structure. The first paragraph in the essay should summarize the entire work. And each subsequent paragraph should defend the first, rather than digress to some fanciful and marginally related sub-plot.

We freshmen squirmed and struggled to compose essays that were linear, succinct, and disciplined — structured from head to toe. Presumably Milton himself never took English 5, because the grand style he wielded in “Paradise Lost” offered no such discipline. Rigorous structure is not for everybody and couldn’t possibly yield the treasures of Churchill’s speeches, much less E.E. Cummings. But for those of us who merely hope that our words will be read and understood, some attention to structure moves the needle.

7. Get to the point.

This being 2020, I wistfully read another blog post today where a tech company announced a layoff. Thankfully, the tweet that directed me to this corporate blog presented the news bluntly, because the CEO’s post didn’t get around to mentioning it until the fifth paragraph. (And what’s worse, he never actually said it at all, but instead spewed vague business jargon until it dawned on me that he was announcing a layoff.) I appreciate the news is bad, but for god’s sake just say it!

Journalists call it burying the lede. I call it wasting the reader’s time.

I get it — there’s context to consider, a certain cushioning to provide to avoid stopping the poor reader’s heart. But, assuming your GFI is at least 18, we’re all adults here, and you really should just say it.

I’ve many times drafted an email or blog post or press release where I dragged the reader through a swamp of rationalizations or context-setting, only to meekly state what needed stating once I could find no further avenue for distraction. As an example, in 2018, I had the unenviable task of telling the company that Upstart’s much beloved first head of engineering, Jonathan, was leaving the company. In drafting the email, I began with the usual blather about how we hire amazing entrepreneurs at Upstart, and naturally expect them to move on to their own ventures at some point. By attempting to convince myself that Jonathan’s departure was a signal of strength for the company, I risked losing our employee’s confidence in me.

But thanks to Professor Spengemann, the first sentence our employees actually read was: “It’s with sadness that I tell you that after more than 6 years of incredible work as part of our leadership team, Jonathan will be leaving Upstart soon.”

It’s better when you just say the damn thing right up front. Your reader can take it — and will in fact appreciate your directness.

8. Break all the rules.

Great writers possess an intuitive sense of the English language and how to harness its powers. In doing so, they can break all the rules. Ultimately, writing has one rule to rule them all — empathy for the reader.

If you can read your words not as you wrote them, but as your reader will experience them, you can become a great writer.

As fall became winter and the end of the term approached, Professor Spengemann informed us that, despite all we had learned, his rules were meant to be broken — just not in his class. When the term ended, the army boots would come off, but the fitness would remain. We would break the rules of English 5, but do so while reflexively and even subconsciously understanding why. I left his class with an inner voice that three and a half decades later still makes me wince at passive tense or too-clever verb forms.

The final goodness that writing offers is clarity of thought. Often the frustrating process of constructing concise and efficient prose reveals limitations in our thinking and holes in our logic. Eventually we get there — the truth is revealed, the point is made. Quod erat demonstrandum. And our investment in writing has led us to the answer.

Images courtesy of Dave Girouard.