With the first half of 2022 in our rearview mirror, it feels like ages ago that all of us were setting our shiny new annual plans and committing to our New Year’s Resolutions (that we were actually going to stick to this time). But given how the last couple of years unfolded, it should be no surprise that potholes abounded on the road and the navigation had plenty of wrong turns along the way.

All told, many might be feeling a bit stuck in neutral — idling along, trying to preserve whatever gas is left in the tank. The natural impulse is to seek out a dose of inspiration to jumpstart your engine and power you through to the next pit stop (apologies for really driving home this car metaphor).

There’s no shortage of startup career advice out there — from Twitter threads and LinkedIn posts, to podcasts and newsletters. But lately, we’ve been focused on finding advice that gets under the hood to the overlooked parts of work, the spots most in need of shining and the development areas that likely aren’t covered by your existing daily or weekly habits.

In hopes of helping to bring you a sense of renewed energy and clarity, we’ve combed the extensive Review archives for tactical guidance from some of the sharpest folks we know on how to get better at specific startup skills you’re probably discounting.

Some of the suggestions that follow are centered around how you interact with others, from reinvigorating 1:1s with your team, to how you can more effectively delegate. Others turn the focus inward, with specific tips on measuring your own progress and soliciting feedback.

Many pieces of advice touch on themes we all know are important, but struggle to prioritize day-to-day, like focusing on our emotional health or reducing bias. Some are simple truths that fall into the easier-said-than-done camp; others offer tips that are more unexpected, like the idea that you should spend more, not less, time with your high-performers, or the notion that you should set “non-goals.”

Whether it’s a helpful reminder or an entirely new habit, we hope you find a dose of motivation and tactical ideas to try out in the back half of the year. Let’s dive in.

1. How to get better at taking your own pulse.

Whether you’re gearing up for a summer vacation or just returning from one, now is a perfect time to hit pause and truly take stock of where you’re at in your current role and your career more broadly — a personal development exercise that’s often left on the back burner.

“When we’re caught up in the daily realities of meetings, messages, emails, docs, asks from colleagues, reports, priorities, new priorities, tickets, decks, memos, and our personal lives, along with the emotional swings that come with riding the startup rollercoaster, it can be easy to succumb to the chaos and lose forest for the trees,” says Brie Wolfson (formerly of Figma and Stripe, and currently of The Kool-Aid Factory — part research project, part consultancy on the topic of company culture).

Wolfson generously shared her personal collection of templates on The Review earlier this year — the docs she uses on a daily, monthly, quarterly and annual basis to stay more focused and make real progress at work, while better understanding and acting on her own career goals, too.

We particularly loved her idea to maintain a monthly personal satisfaction doc. “Many of us will be familiar with C-Sat, short for customer satisfaction, as a metric for how satisfied customers are with a product or service. Many of us will also have filled out a company satisfaction survey (also known as an employee voice survey) that contributes to a broad company satisfaction score and accompanying read-out about how satisfied employees are with their companies. I say it’s time we all get in the habit of turning this question on ourselves, and evaluating our own satisfaction, or ‘Me-sat’ on a monthly basis.

There are lots of ways to take your own pulse, and Wolfson leans on several different exercises. “I like to switch up the framework for my reflections to keep them fresh. No matter which exercise you go with, the most impactful things for me have been getting in the habit of taking some time and space for self-reflection (i.e. actually doing one of these exercises with some regularity) and looking backwards to identify patterns in a way that helps inform future behavior,” she says.

Building a regular practice of putting all the pieces together, through targeted self-reflection, can help you hone in on the story you tell about yourself about where you’re at and where you want to go.

Here’s her list:

- Satisfaction Litmus Test: A simple structure for a check-in, taken from my favorite planner, designed (and sold!) by David Singleton, Stripe’s Head of Engineering. All this exercise requires is that you score yourself between 1-4 on four core drivers of satisfaction: enjoyed it, got stuff done, progressed goals, learning. Average them together (or use a weighted average if you’re feeling extra thorough), to generate an overall “Me Sat.”

- Blood Kool-Aid Content: One way to describe “Me Sat” can also be your current Blood Kool-Aid Content. As in, how much of the company’s Kool-Aid do I have pulsing through my veins? Or, how into the company’s mission, leadership, coworkers, role, and operating norms am I at a given moment? This single-prong score can be susceptible to bias by your current mood, but it never hurts to track it. (Or, ask yourself where you’re at on this scale when you’re feeling extra charged up about something as a way to build more self-awareness and take more measured action).

- Contribute to Your “Four Lists”: This one’s coined by Molly Graham (Google, Facebook, Quip, Lambda School, Chan Zuckerberg) and suggests you contribute to four lists; things I love doing, things I’m exceptional at, things I hate doing, things I’m bad at. I like to use these as running lists as opposed to making a new one every month. Take note of what changes — maybe even track them in a changelog.

- Energy Assessment: Similar to Molly’s four lists, and introduced to me by Stephanie Zou (Zendesk, Figma) this exercise helps you articulate how the things you work on impact your energy, and what you would like more and less exposure to over time.

- Stop, Start, Continue Retrospective: This classic retrospective framework asks you to consider what you want to start, stop, and continue doing. It’s often used to reflect on collaborative or cross functional work, but there’s no reason you can’t use it for yourself! Here’s a template if you want to try it yourself.

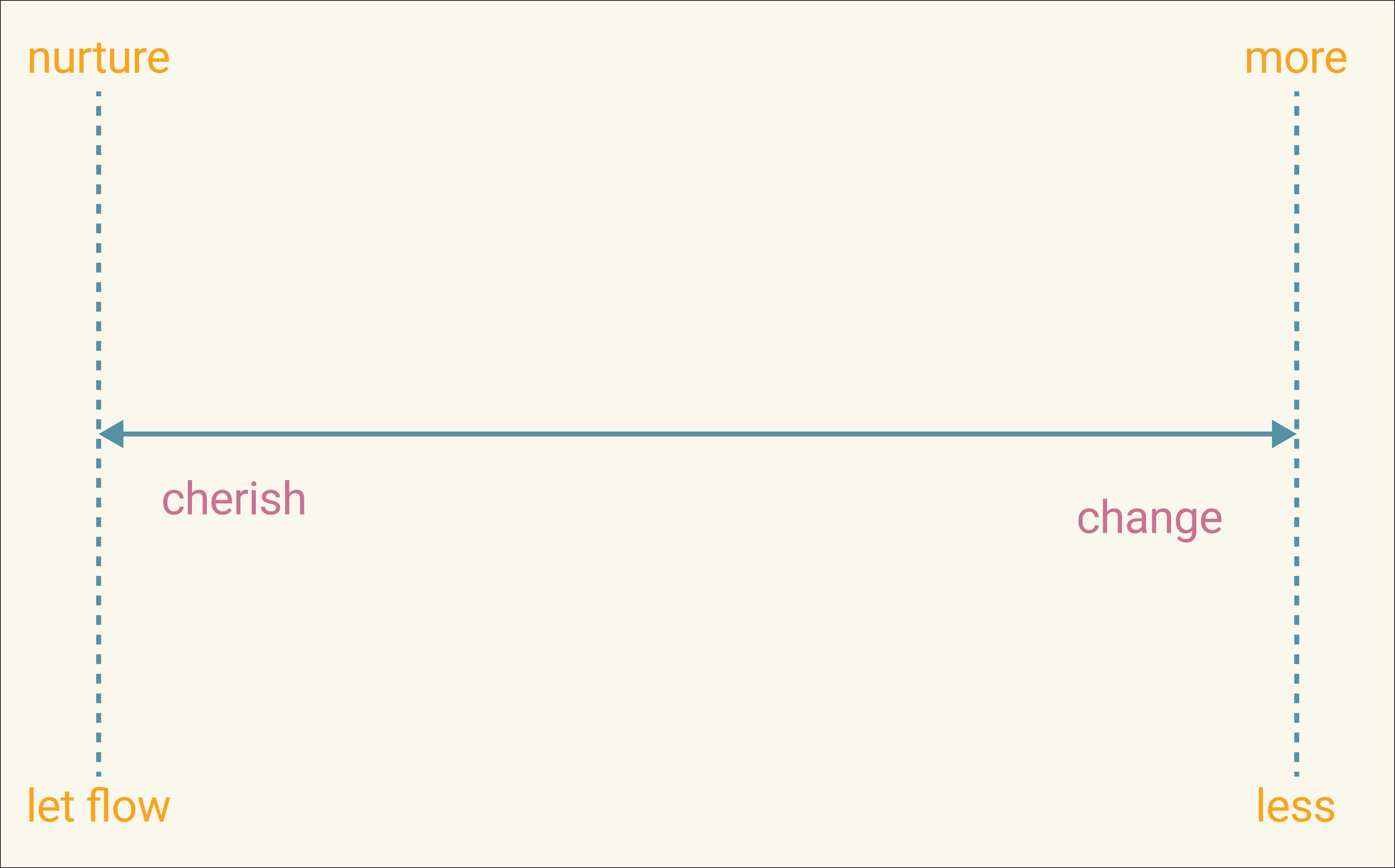

- Cherish / Change Retrospective: Another retrospective framework I’ve been playing around with is the Change / Cherish Scale. On one side of the spectrum, I have things I want to hold on to. From there, I ask myself if I want or need to nurture this thing (as in, focus some attention on gardening/watering it) or let it flow (as in, don’t intervene and let things happen.) On the other side are the things I want to change. From there, I’ll ask myself if I want more of it or less of it. Here’s a template if you want to give this one a try.

2. How to get better at delegating.

Sam Corcos, four-time founder and current CEO of Levels, admits he’s a bit obsessive with optimizing his time as a startup CEO. (See this deep-dive into how he meticulously tracked every 15-minute increment for two years as proof.)

The productivity hack he believes most startup leaders are overlooking? Delegation. “Learning how to delegate effectively is perhaps the single most important skill that folks need to develop in order to transition into a leadership role, and yet, many are reluctant to embrace it. Delegation is a superpower. It also takes practice,” he says.

To get better, Corcos suggests tapping into one of the most under-utilized resources available to every startup: support staff. “When leveraged correctly, executive assistants can be one of the most important tools in a startup team’s arsenal — freeing up space to focus on the thorniest challenges facing the business. But there isn’t all that much tactical information out there on how to specifically work with EAs — often, it’s just something leaders are expected to know how to do.”

On The Review earlier this year, Corcos shared a window into how he works with EAs at Levels, outlining several specific tips you can use whether it’s your first time bringing one on board, or you’re looking to better leverage the EAs you already work with. Below is a sneak peek at some of his favorite tactics:

Go async.

“This is going to feel unnatural for most people, but you should try to lean into recorded, asynchronous video and voice memos for delegation. It’s way more time-efficient for you and your EA, and it allows that video recording to be used as an asset in the future when new people need to be onboarded to the task. It’s way easier for someone to watch a recording than it is to have a new, synchronous onboarding call with every new person for every task,” says Corcos.

In fact, Corcos has been working with a group of outsourced EAs regularly for over a year, and they’ve never had a single synchronous meeting — everything is async. “When it comes to using asynchronous videos with EAs, the most important tip (and the one that takes some getting used to) is to always record in one take — it’s okay if there are awkward pauses or it's more of a stream of consciousness,” he says.

Define the output from the start.

It’s almost always better to make it clear to your EA what type of formatting you’re looking for. Should the deliverable be a spreadsheet? If so, what are the columns you’re expecting? Should it be a presentation? A Notion doc?

“If you ask, ‘Put together a list of all the podcasts that Bob Smith has done,’ it will save everyone time if you spend another couple of minutes putting together the initial spreadsheet that shows what columns you want — like the URL, title and podcast name” says Corcos.

Try partial implementation.

If a task requires meaningful time (e.g. more than a couple of hours), it’s almost always a good idea to ask your EA to do a partial implementation of a task before you spend significant time on it.

“If you have a task that will likely take 20 hours of work to complete, you should almost always say something like, ‘Can you spend 10 minutes working on this and send me the result so I can double-check to make sure we’re going the right direction?’” says Corcos. “This will save you a lot of pain because it prevents your EA from spending time on something that isn’t right.”

As an example, each week Corcos’ EA puts together the first draft of the summary slide for the weekly all-hands. “This is a task that used to take 2 hours per week, but now takes less than 15 minutes because the bulk of the work is already done by the EA by the time I start working on it,” he says.

3. How to make your strategy more clear.

If you’re like most leaders, you’re likely struggling to spend enough time on strategy, instead getting pulled down into the tactical weeds of everyday execution. “Nobody wants to dedicate the time to think through strategy holistically. The idea that you’re going to spend 2-4 weeks having these really wide-sweeping conversations is antithetical to how startup folks work on a daily basis,” says Ravi Mehta, CEO of Scale Higher and former CPO of Tinder.

“But if you spend a few weeks approaching this work in an intensive way, you’ll avoid doing a half-assed job over the next two years,” he says. This is particularly critical for product leaders. “Without a solid product strategy you end up with products that have a Vegas effect — there are so many flashing lights vying for the user’s attention because each team has its own isolated goals.”

Mehta shared his entire “product strategy stack” playbook on The Review earlier this year, but one oft-overlooked area particularly stood out to us: The importance of setting what he calls “non-goals.”

“One of the hardest things that happen with the process of coming up with a strategy is people come with their own expectations about what they want to see from the company and from the product. And when the strategy document is not specific enough, everyone walks away with a different opinion of what the strategy is, through the lens of what they think is most important,” he says.

“As part of the strategic planning process, you’re making choices. It’s important to document those concrete choices — not just that we’ve chosen to do A, but also to explicitly reinforce that we’re not going to do B,” he says.

In your product strategy document, be sure to include slides that outline the non-goals: “This should cover elements or questions that came up during the product strategy process that were particularly controversial. Be very clear about what decision was made and where folks disagreed but committed,” he says. It’s really important to have a clear set of choices, make sure everyone in the org understands what those choices are, and deliver something that is clear and opinionated to the customer.”

As product leaders, every choice we make is a choice that we save our users from making. If we're not clear about what we want our product to do, we shift that lack of clarity to the user.

4. How to speak less and become a better detective during 1:1s.

In the mad dash of meetings, must-do tasks, and constantly shifting priorities, weekly 1:1s with your direct reports can become rather rote. Status updates and small talk abound, and soon enough, these weekly sessions can morph into less-than-exciting line-items on your managerial checklist.

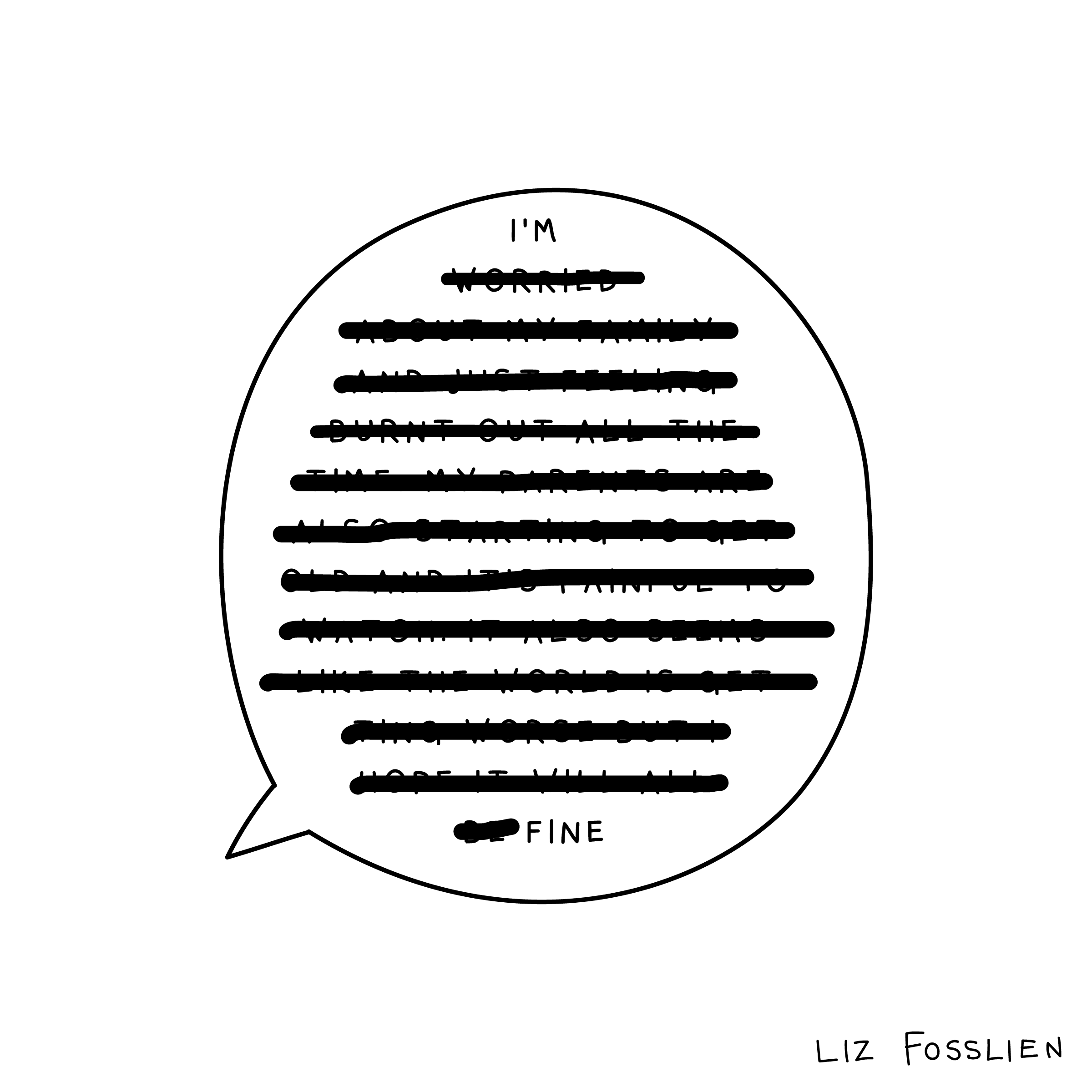

“If your 1:1s focus solely on tasks, you’re missing out on a valuable opportunity to better understand and support your reports. Worse, you might be inadvertently sending the message that you care only about pressing to-dos, which can leave your team feeling expendable and anxious,” says Liz Fosslien (illustrator behind the delightful @Lizandmollie Instagram handle, author of “Big Feelings: How to Be Okay When Things Are Not Okay”, and Head of Content & Communications at Humu).

There are also real benefits to taking a different approach. “Our research at Humu shows that people whose manager makes an effort to help them combat burnout are 13X more likely to be satisfied with their manager,” she says.

Fosslien shared tons of tactical advice on how managers can help their teams face down burnout and uncertainty on The Review earlier this year if you’re interested in learning more, but we particularly loved this simple mandate: “Your job in 1:1s is to make each person feel heard,” she says.

As something of a sidebar, it reminded us of a related prompt for managers we heard earlier this year from The Grand’s Anita Hossain Choudhry: How many times did I ask questions versus give answers this week? “It's important to do a gut check and gauge how much we as managers are in fix-it mode versus listening empathetically and asking open and honest questions,” says Choudhry. Think back to your last 1:1. How much were you speaking and how much was your report speaking?

But as Fosslien notes, this focus on reducing speaking time doesn’t mean managers should clam up altogether. “Often you’ll have to do a bit of detective work, as your reports may not be inclined to surface that they’re struggling,” she says. “You have to check-in in an authentic and meaningful way. Say one of your reports is an under-emoter. If she’s feeling overwhelmed, she won’t wear that emotion on her sleeve. She likely won’t bring it up in a 1:1 conversation on her own — and she won’t volunteer much to an overly broad ‘How can I help?’ question.”

Dig a bit deeper by asking questions like:

- What part of your job is keeping you up at night?

- What should I know about that I don’t know about?

- How does your workload feel right now?

- Is there anything I can take off your plate, help you delegate, or help you deprioritize?

- What one thing can I do to better support you? “The ‘one thing’ is critical here. It solicits more and better responses than a more generic ‘Is there anything I can do?’”

- What kind of flexibility do you need right now? “You could even give examples, like a doctor’s appointment, needing to turn your camera off, or dealing with a family issue.”

- Is anything unclear or blocking your work?

- What was a personal win this week, and what has been a challenge?

5. How to get better at listening — by paying more attention to yourself.

“It’s very common to have a goal to work on your presentation skills or become a better public speaker. There are tons of trainings you can take, and we’ve generally agreed culturally that those are important skills to hone. But listening is the other part of that equation — and we don't pay very much attention to it,” says Ximena Vengoechea. “You're going to get greater alignment more quickly when you're able to really listen and hear out someone’s ideas, rather than just fine-tuning your own pitch.”

We often think of miscommunication as an issue with our own content or delivery — that if we could tweak the what or the how, our message would be more effective. But that perpetuates a dynamic where we view our counterparts as an audience, not as collaborators.

Tapping into more than a decade of experience as a user researcher at companies like Pinterest, Twitter and LinkedIn, Vengoechea quite literally wrote the book on listening, publishing “Listen Like You Mean it: Reclaiming the Lost Art of True Connection” last year. (On The Review, she shared an excellent primer on listening specifically for the startup setting, so we recommend starting there.)

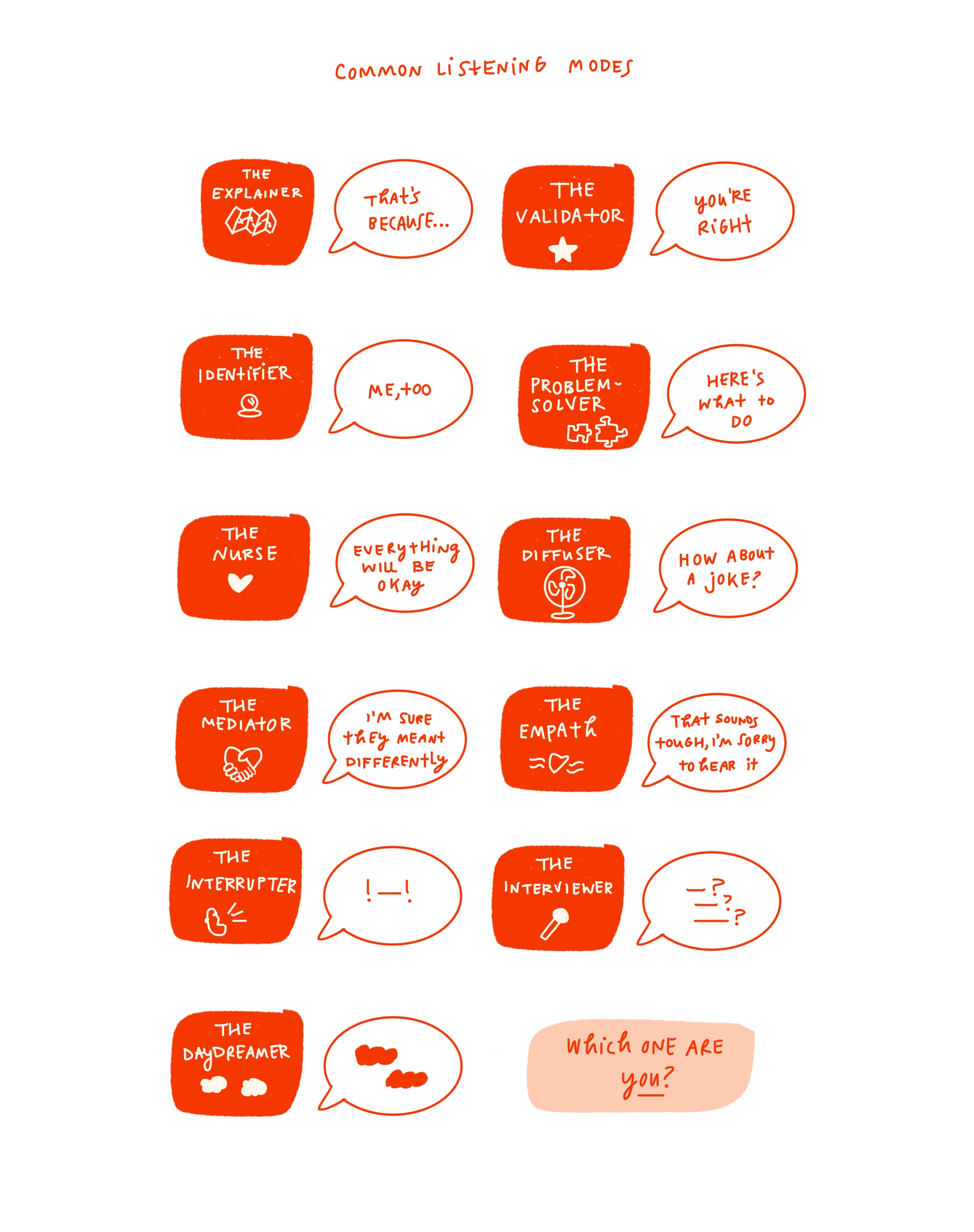

We loved this tip of hers in particular: “When thinking through how you can show up as a better listener, it’s important to remember there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. But one tool that can be helpful is identifying your default listening mode,” says Vengoechea.

“It’s the natural filter that you tend to use when you show up in conversation. For example, you come in with a mediating listening mindset, where you're listening for everybody's role in a certain situation. Or you might have a validating listening mode, where you’re looking for ways to affirm the other person,” she says.

“Each of these modes have their ups and their downs. The key is to identify yours and then gut check yourself to see if that's what's needed in a particular conversation — or if you need to switch up your style,” she says.

It’s easy to assume that listening is merely about showing up and paying attention to the other person, but it’s also deeply tied to paying attention to ourselves. Being an effective listener is about building self-awareness around how you naturally show up in conversation.

Here are a few pointers for putting this into practice:

- Take this quiz to do a deeper diagnostic of your default listening mode.

- Vocalize your gut. “You can even say to your direct report, ‘Normally, my instinct here would be to offer you advice — is that what you're looking for?’ Sometimes being willing to say, ‘Even though I’m the manager, I don't necessarily know the right response here — what would be useful for you?’”

- Open up space. “There’s power in asking ‘Would you like me to listen, or brainstorm solutions with you?’ Sometimes they just want to vent and it’s cathartic. As a manager you may hate it, and it can be unproductive if it happens too often, but occasionally creating space for that is part of your role.

6. How to better support the team members you’re likely overlooking.

Molly Graham often tells managers to assess their calendars, not purely for time management purposes. “You should be spending the majority of your time with the people who are moving the needle — the folks who are your highest performers and have the potential to change the company. It's really easy to think, ‘That person is so strong, they just take care of themselves. I'll go focus on the rest of my team,’” says the seasoned company builder, formerly of Lambda School, Quip, and Facebook. (She recently started a Substack newsletter that we emphatically recommend subscribing to.)

Matt Wallaert (Head of Behavioral Science at frog) offers a similar piece of counsel. “My approach to management is about fighting cognitive biases. Humans have a recency bias, meaning we tend to overweight recent experiences. In management that means I’m mostly paying attention to whoever I talked to last — as the saying goes, ‘The squeaky wheel gets the grease.’ So I try to be on alert for the people who I haven’t heard from,” he says. “It’s often because they are deep in the thick of something and could use support — but aren’t asking for it. Sometimes folks are quiet because they’re chugging right along — and I want to celebrate that with them.”

For Graham, it’s not just about celebrating, but pushing the limits of those achievements. “I firmly believe that the majority of my time and coaching energy should actually go into people who are high-performing. They are the rocket ships that could end up running parts of the company someday,” she says. “To me, as a manager you’re looking to bring out the maximal optimized version of each person. So when you have someone who’s doing really well, the question should be, ‘How can they do even better? How can you make their growth explode?’”

One technique Graham leans on is a “look back, look forward” every couple of months or at the tail-end of a project. “I run through these questions, which are from a strengths-based philosophy of management — the idea being that if you can figure out the alignment between what people love doing and what they're good at, you can find the best version of them,” she says.

Look back:

- What did you like about that? What felt good?

- What did you hate about it? What didn’t feel good?

- What's the most important thing you learned?

- Do you want to do more of that type of work, or less?

- What do you want to do differently next time?

Look forward:

- What’s the next challenge?

- What's the next big step or career goal you want to reach for?

- What type of work do you want to take on, whether it’s a current project in the company or something that might potentially show up in the future?

7. How to get better at asking others to weigh in.

You probably ask others on your team to weigh in all the time, whether it’s to debate the finer details of a deck you put together, or to poke holes in a big strategic initiative you’ve been considering. But when you’re moving fast, you might not be as effective at surfacing different perspectives as you could be.

“It’s great to have other people make the same judgments as you to uncover where there’s dispersion of opinion— but that only works if the judgments are independent. To achieve that independence, don’t let others know what you think before you find out what they think,” says former poker player, decision-making expert, and bestselling author Annie Duke. “In a group, there’s the added element of cross-influence. People are going to try to convince each other. There’s going to be contagion, and sometimes it can even become combative, which is bad for decision-making.”

That’s why it’s critical to ensure that initial feedback is collected asynchronously and independently. For big-ticket decisions, consider running a process like this one: “Get everyone to rate each attribute on a certain scale, like zero to seven. That way you can see everybody's opinion and pinpoint the places where opinions don’t align,” says Duke.

For a more lightweight process or lower-impact decisions, there are several tactics to try out:

- Have team members write down their opinions anonymously on a virtual whiteboard. Or if in person, have them write it on a piece of paper to pass along so someone else can read their take.

- If folks on your team are sharing their own opinions aloud, go in reverse order of seniority.

- When sending an email asking for feedback on an idea, ask everyone to email you directly instead of replying all. Then aggregate the results and share out.

For more lightweight tactics backed by decision science, see Duke’s playbook for founders in full over here.

8. How to attract more specific feedback.

There’s a lot of advice out there on how to artfully give feedback to others, but not so much on how to attract useful feedback about ourselves — especially outside of the semi-annual, awkward window of performance reviews.

That’s why we liked this self-reflection question from HubSpot’s Sara Rosso: When was the last time I asked for feedback?

Chances are, not very recently. Which is a missed opportunity, because more likely than not, your colleagues already have feedback for you — they’re just not saying it aloud. This realization was key to transforming Shivani Berry’s career growth.

“They’ve had thoughts like, ‘Sarah NEEDS to stop saying ‘um’ so much in meetings,’ or ‘Ugh! Here I go again, working with Mike, who’s never gotten a deliverable to me on time,’ or ‘Once again, I have no idea WTH this person is trying to say.’ Unfortunately, people typically don’t volunteer that kind of feedback unless they’re forced to put it into a performance review,” says Berry, the founder and CEO of Ascend.

“In fact, they actively avoid giving it because it makes them uncomfortable. To break through this type of fear and discomfort, you have to get proactive. You have to go out of your way to attract feedback, become a feedback magnet,” she says.

It’s not enough to make a simple ask slightly more regularly, however. “Usually when I ask for feedback, I just hear, ‘You’re doing good’ or ‘There’s nothing I can think of.’ That doesn’t tell me how to be better. To help get the unfiltered truth, you need to do more than just invite people to give you feedback; you need to remove any and all friction,” says Berry.

“The biggest sources of friction include: people’s unspoken fears about giving you negative feedback, uncertainty about how to phrase their feedback, and self-consciousness about whether their feedback is useful.” Here are two of Berry’s tips removing this friction and for sourcing the kind of feedback that actually helps you improve:

Narrow the question:

Instead of asking vague questions like, "Do you have any feedback for me?" or "How can I improve?" ask specific questions to unearth truly constructive feedback. A narrow question reduces the mental burden for your colleagues to identify how you can improve. It also gives them permission to share candid feedback because they’re telling you about something that you’ve already identified as a potential problem.

Some examples:

- How can I exceed expectations?

- How can this deliverable be 10% better?

- What would make you “love” this instead of just “like” it?

- Was I saying “like” too much in the meeting?

- Did you feel comfortable sharing your opinion in our last meeting even if you disagreed with the group?

The quality of your questions determines the quality of the feedback you receive.

Ask for a rating:

When stakeholders hesitate to give me honest feedback, I ask them to rate my performance or idea on a scale of 0-5. They rarely say “5”. Then I follow up by asking what I could have done differently to make it a 5? This approach is disarming, and reiterates that I’m truly interested in improving which motivates them to start coaching me.

For example, I asked one of my reports to rate how well he felt I had set him up for the task he was working on. When he rated it a “3,” I realized that I wasn’t setting clear expectations. Moving forward, I was more explicit about what successful completion of a task looked like.

9. How to proactively take care of your emotional health.

“Founders will go above and beyond to do what’s necessary for their company. But they often stop short when it comes to fulfilling this same commitment to themselves and their mental wellbeing,” says Dr. Emily Anhalt, PsyD. “And far too often we see the consequences of a failure to do that self-work when startups implode, whether it’s due to a toxic work culture, co-founder conflict, or deep-seated leadership challenges.”

In the face of long hours, the turbulent financial path to building a new company, and pressure to make key decisions, founders confront a unique set of mental wellbeing challenges. As an experienced psychologist and co-founder of Coa, Anhalt’s made a career of studying entrepreneurs, and time and time again she’s seen it proven out that if founders make their emotional fitness a priority, it will reverberate through their companies, forging more resilient startups with healthier cultures and happier employees. “Strong companies take shape when emotionally fit founders are sitting at the top,” says Anhalt.

She chose the words emotional fitness intentionally. “Even if you aren’t feeling ill, that doesn’t mean you have a clean bill of physical health. You may not be exercising or eating healthy. Preventive care is crucial — when you work on your physical fitness, you get stronger and you’re less likely to get sick later,” says Anhalt.

“Emotional health is similar. Many people wait until they’re having debilitating anxiety before they start to think seriously about taking action. Maintaining emotional fitness is an ongoing, proactive practice that increases self-awareness, positively affects relationships, improves leadership skills and prevents mental and emotional health struggles down the line. Think about it less like going to the doctor and more like going to the gym,” she says.

Just because founders aren’t having daily panic attacks does not mean that they are emotionally fit.

And in the midst of topsy-turvy economic conditions and heaps of uncertainty, this advice is more prescient than ever. “The ability to work through exhaustion can get founders from point A to point B, but it isn’t sustainable. Start on your self-care now,” says Anhalt. Here’s one exercise to get started:

Practice mindfulness by scheduling an hour for worrying.

Mindfulness is a word that gets tossed around with all sorts of different meanings. For Anhalt, mindfulness is about getting comfortable with being uncomfortable – she likens it to how the practice of yoga involves holding your body and settling into poses that might feel uncomfortable in the moment.

And in some cases, mindfulness means sidestepping the founder instinct to anticipate the future. “There’s a difference between scenario planning for the future and thinking through what your company might look like in six months versus trying to figure out how to deal with emotions that are tied to things that haven’t happened yet,” she says. Along those lines, Anhalt suggests scheduling a “worry hour” – blocking off a slot on your calendar where you get to be as worried as you want for that amount of time.

“It sounds a little trite, but if you schedule time to worry, that means you’re able to be more present for the rest of your day, rather than feeling constantly overwhelmed by tides of anxiety, which ripple out to impact how you interact with others,” says Anhalt. “When you find yourself getting worried, perhaps tossing and turning in bed at 2:00am, gently say to yourself, ‘That’s not my problem right now, that’s ‘6:00pm me’s’ problem. I’ll worry about it then.’”

We often make the mistake of allowing ourselves to slip into tomorrow’s worries instead of handling the challenges of the moment. But we’re suffering future pain, needlessly.

Cover image by Getty Images / jayk7.