This article is by Anita Hossain Choudhry and Mindy Zhang, who have coached hundreds of managers. Hossain Choudhry is CEO at The Grand, a group coaching platform to support managers in making leadership decisions. She’s also an executive coach (formerly at Reboot.io) and previously the Head of Knowledge at First Round Capital. Zhang is a former product leader at Dropbox and at Oscar Health, and is now an executive coach at Throughline and The Grand.

Think about your typical week as a manager. How many times did you help your direct reports by trying to solve their problem? The answer is probably as many times as you met with them. While that’s common among managers, it’s not always optimal.

Too often, managers feel the best way to add value is by fixing someone’s problem. “I know the answer, and I need to tell them,” we say to ourselves. But over-relying on fixing constrains our ability to lead and robs our team members of growth opportunities.

As a result, many managers get overwhelmed with responsibilities and burn out. They create a team culture in which they’re expected to have the answers. And their direct reports — instead of utilizing their talents and stretching their problem-solving skills — become dependent on their managers to do their jobs.

Managers are not solution vending machines. They’re not paid to give answers.

Great managers know they need to invest in the long game: building a team that is constantly growing, feels empowered to drive results, and reaches higher levels of performance.

In our experience, many managers stumble here because they lack the knowledge about what else to try. Especially in the startup setting, manager training is often inadequate (if it even exists). Most managers haven’t been taught how to assess their style or shift their approach — many bring the best of intentions, but frankly, simply end up winging it.

But if they aren’t aware of it, most managers default to a single approach. Daniel Goleman, a psychologist and leadership author, studied 3,871 executives and identified six leadership styles: Commanding, Visionary, Affiliative, Democratic, Pacesetting, and Coaching. What he found was that the most effective leaders didn’t over-rely on a single style; they had mastered multiple styles and could skillfully match the right style to a situation.

Similarly, as a manager, you have a toolbox of skills, styles, and competencies to pull from. In order to be the best manager possible, you need to: (a) assemble a diverse and varied toolbox, and (b) wisely select the tool that will be most useful in a given situation.

As executive coaches, we’ve worked with hundreds of startup managers. We’ve seen first-hand that coaching is one of the least utilized and yet most effective management tools. (In fact, in Goleman’s research, coaching was rated as leaders’ least preferred style, even though it correlates with positive team dynamics.) By adding coaching to your toolbox and calling upon it in the right situations, you can uncover your team’s blind spots, help your direct reports grow into more capable leaders, and ultimately, enable your team’s best work.

In this article, we’ll unpack why managers fall into the fixing trap and dig into the fundamentals of coaching, sharing four actionable tools you can start using immediately. We’ll distill the highlights of what we’ve learned in years of coaching training — all adapted to everyday management scenarios so you can see how to practically put them to use.

THE DEFAULT APPROACH: FIXING

Picture this: You’ve just finished your morning coffee and call into a regularly scheduled 1:1 with a high-performing direct report. Before you’ve had time to chit chat and establish an agenda, they express frustration about their role:

“To be honest, I haven’t been feeling motivated at work. I tend to be bogged down in execution details, and I’m not getting enough exposure to strategy. I look around, and my peers are working on strategic projects that move their careers forward.”

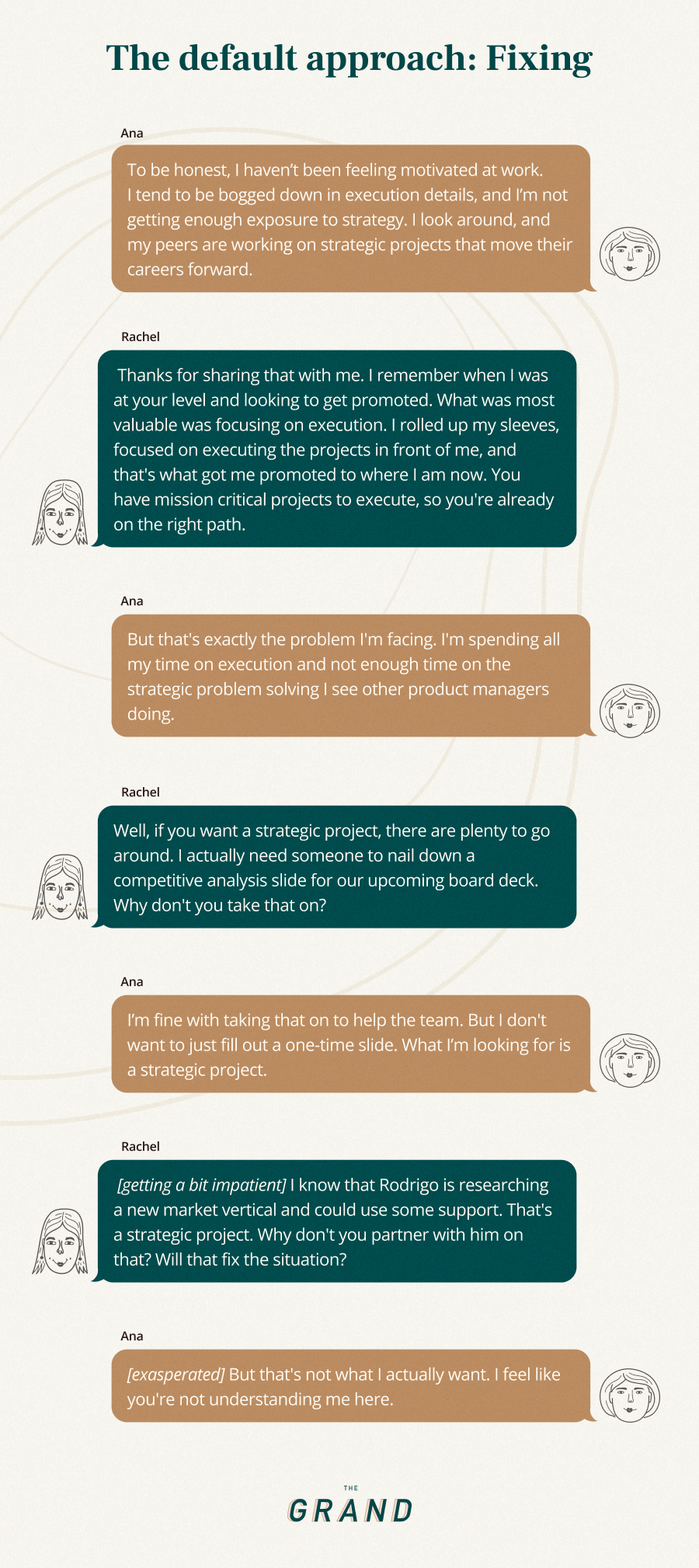

How would you approach it? Most managers start scanning for problems. Once they’ve identified a problem, they jump straight to fixing it. Take this example of the manager (Rachel) and her direct report (Ana). If Rachel uses a fixing approach, here’s how that conversation might go:

What did you notice about the conversation above?

First, the manager started with advice from her own experience. She assumed that her direct report was asking for strategic opportunities in order to get promoted, and that sharing lessons from her own career advancement would be relevant. While those assumptions might be true, it’s also possible that her direct report has a different “why” behind the ask — for example, acquiring a new skill, gaining confidence, or charting the course for a different career path.

Second, the manager prescribed solutions — creating a competitive analysis slide, partnering with another colleague on a strategic project — before understanding the root cause of the problem. The manager and direct report engage in a frustrating game of ping pong. The manager suggests a solution, and the direct report counters it. Little progress is made. The manager exits the conversation thinking that their direct report is difficult, entitled, and not focused enough on their core role. The direct report leaves feeling unheard and dismissed.

We’ve encountered this very situation in our own careers. When Anita was managing several people who had just graduated from college, she reflected on her own first job — and was reminded of a manager who was unclear and didn’t offer the right level of support. Vowing to do the opposite, when a direct report came to her struggling to prioritize everything on her plate, Anita immediately jumped into fix-it mode, getting super prescriptive.

She told her to take a sheet of paper, draw a triangle on it, and then break it up into thirds. In the bottom of the triangle, Anita wrote down 3-5 things her report should work on for the week. Next, she outlined three things for the next three days in the middle section, and the one thing that she needed to complete before she left the office for the day at the top of the triangle. Anita did this for her direct report every day for several weeks, thinking she had solved her problem. Oftentimes, Anita would also look at that triangle and take a few things off of her plate and just do it for her, trying to lighten the load. Yet the direct report’s creativity started to wane as she spent long hours trying her best to get those critical tasks done.

Why managers are prone to fixing:

Situations like this are common in manager-report relationships. When a manager adopts a fixing approach, they assume that:

- 1. Their experiences are relevant to the other person’s situation.

- 2. They know the other person’s problem well enough to prescribe advice.

A fixing approach isn’t always bad. Sometimes, we do know the other person’s situation accurately, and our advice is tailored to their specific problem. But in many management situations, jumping straight to fixing causes (a) a misinformed solution that makes the problem worse, (b) a band-aid solution that temporarily soothes the wound but doesn’t solve the deeper issue, and/or (c) a long-term dependence on the manager to fix all problems, thereby depriving the direct report of opportunities to grow and solve their own challenges.

Why do managers instinctively dive into fixing? Two big reasons:

- We think we know: We got promoted into managerial roles from senior individual contributor (IC) positions because we excelled at building our expertise and swiftly applying it to solve problems. We’re wired to think, “I know the answer and can add value here” and jump into action.

- We think we should know: Many managers (particularly those who are new to managing people) experience imposter syndrome. They might think, “I should know the right answer. Otherwise, if I don’t, I’m a bad manager.” To protect our own credibility, we take on immense pressure to fix problems.

Being the hero who swoops in and relieves someone of their problems feels good, and it’s hard to let go of the chance to reinforce our competence.

Many have had brushes with that second one in particular. When Mindy became a people manager at Dropbox in her mid-20s, she battled imposter syndrome as she managed people with up to a decade more experience. Whenever a direct report came to her with a challenge, a negative talk track kicked in. She thought: “I need to solve this problem for them, now. Because if I don't... Well, they'll know that I'm faking it. That I'm not a real product leader."

As a result, she often overworked herself solving team members’ problems, and most of the time, her solutions were misinformed because she didn't have full context. A wake-up call came while working with an executive coach who did a round of in-depth 360 feedback that scored her across dimensions of leadership. “Keeping talented people challenged” was her lowest score. Mindy realized that the amazing product managers she was hiring were joining her team so that their strengths and expertise could shine, not so she could take on their problems.

THE ALTERNATIVE APPROACH: COACHING

In many management situations, coaching is the most effective approach. Coaching allows us to shift the focus away from ourselves and onto the person we’re coaching.

Of course, this term is still a bit fuzzy, especially in the startup world, where coaching can take many forms. We define coaching as getting someone from where they are to where they want to go by tapping into their own wisdom and keeping them accountable to achieving their goals.

To put it simply: Coaching is a skill, while being a manager is a role.

The key element is tapping into their own wisdom, not your wisdom. When we constantly support our teams using our wisdom, we are hyper-focused on solving the problem at hand based on our past experiences and learnings.

Returning to Anita’s own management example, an “aha” moment arrived during her first coaching certification course. One of the training sessions talked about how we often live our lives according to someone else’s compass. Only through deep inquiry and by asking open and honest questions can we know our own compass. Anita realized that by adopting a fix-it management approach, she was trying to get her direct report to use her compass to define success — and as a result, the employee was no longer connecting with the work that had her so excited in the beginning.

In their next 1:1, Anita instructed her direct report to take the lead filling out that triangle. To aid in the process, she asked open and honest questions about what type of work her team member was most drawn to and where she saw opportunities for the firm to grow. By taking a coaching stance, Anita helped her trust her intuition and develop her own compass. In turn, this allowed the direct report to come up with some of the most creative ideas deployed at the company, returning to the vibrant and innovative person Anita had hired in the first place.

When we instead use coaching to unearth someone’s own wisdom, two things happen:

- We invest in their inner teacher: This means that you’re not just solving a one-time problem; you’re helping them see patterns and behaviors so that going forward, they can develop their own resources and best practices to navigate their challenges.

- We empower them to trust themselves: You’ll see a shift in your team member’s ability to more clearly and confidently articulate next steps they can take to solve a problem or achieve their goal.

Coaching 101 = Empathetic listening + open and honest questions

Before sharing a few coaching tools, we want to dive into two foundational skills that are essential to start coaching your direct reports: Empathetic Listening and Open and Honest Questions

To highlight empathetic listening, we need to start by defining the opposite of empathetic listening, which is self-focused listening. We’ve all been there before. Whether it's in a 1:1 with a direct report or a cross-functional meeting, we often listen to other people in order to answer one question: What does this mean for me?

We are listening to react and respond: What should I say next? What conclusion should I draw? How should I interpret this? What does this person need from me? How do I help them figure this out?

This is a natural human reaction because our brains are designed for pattern matching and problem solving — which can be quite useful in many parts of our lives. Instead, we recommend that managers use empathetic listening.

Empathetic listening means shifting from "What does this mean for me?" to "What's going on for this person?"

At its core, empathetic listening is:

- Listening to understand another person's experience: What's going on for them? What are they thinking, feeling, and experiencing?

- Staying curious and open to possibilities — including things that might surprise us or change our minds.

With this insight, we unlock previously hidden information that enables us to better guide the other person. It’s important to clarify that empathetic listening is not:

- Feeling the same feelings as someone else — this can lead to taking on other people's distress, a significant cause of burnout among managers.

- Comparing the other person's experience to your own.

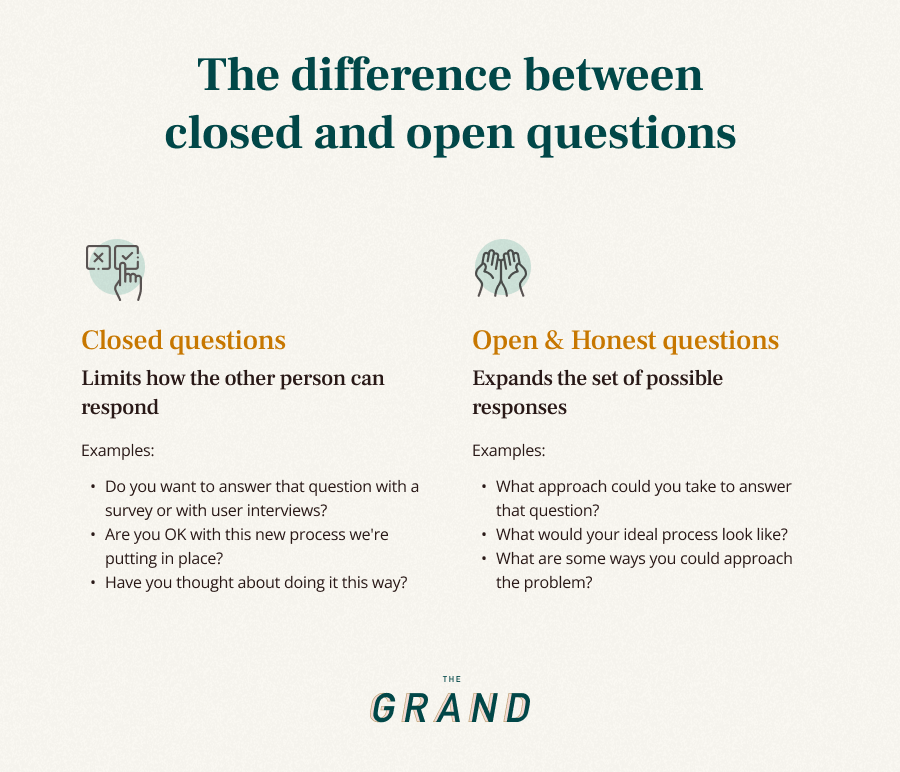

The second foundational skill of coaching as a leader is asking open and honest questions. Generally, questions can be closed or open. A closed question limits how the other person can respond.

For example:

- Do you want to answer that question with a survey or with user interviews?

- Are you OK with this new process we're putting in place?

- Have you thought about doing X to solve the problem?

Sometimes, this approach can be useful. For example, if we need to make a fast decision on an urgent issue, we may not have the time to explore the full range of possibilities.

But when we coach as managers, however, open and honest questions help someone gain insight and draw out their best ideas. An open and honest question expands the set of possibilities for the other person to respond with. The way you know it’s an open and honest question is if you say yes to the following list:

- I don’t know the answer to the question.

- I don’t have a preferred answer.

- I’m not trying to steer the person in a particular direction.

FOUR PRACTICAL COACHING TOOLS FOR MANAGERS

Learning how to coach is a life-long journey, but we’ll start you off on the path by sharing four actionable tools that you can start using immediately as a manager. For each tool, we’ll outline a practical scenario, flag what the fixing approach looks like, and share tips for applying the coaching technique instead.

Coaching Tool #1: Outcome Shift

When to use it: A team member is spinning on a problem — for example, an unexpected constraint in their project. They’ve thought about it, but are stuck on how to proceed.

If you took the fix-it approach, you might default to saying: Why is this happening? What’s going to be the impact on our team’s OKRs? How do we solve this problem?

Here’s why you should use coaching instead: When someone is stuck on the problem they're facing, they haven't even tried to picture what they want from the situation. And without knowing what they want, they can't move towards it. Coaching can help them shift them from the problem to the solution, so they can start mapping out the path from A to B.

How to apply this tool:

- “In this situation, what would you like?” (Repeat this back to the other person to make sure you heard correctly)

- “What will having that do for you?” (This question helps them dig one level deeper on what they’re solving for)

Pro-tips to keep in mind:

- Repeat the second question as many times as you need until you get to the core of what your direct report wants out of the situation.

- Use the exact wording of the questions. For example, saying “will” instead of “might” presupposes that your direct report will achieve this goal in the future and puts them in a mindset to do so.

- If what your direct report wants isn’t tractable — for example, they want a difficult colleague removed from the team — you can explain why it’s not feasible, then ask: “Let’s keep exploring to see if there’s another possibility. Given the way things are, what else would you like?”

Coaching Tool #2: Options Exploration

When to use it: You understand your team member’s challenge and what they would like to see happen. You want to partner with them to solve it.

If you took the fix-it approach, you might default to saying: Have you tried doing X? I can step in and take this on for you.

Here’s why you should use coaching instead: Your direct report may have context and ideas that you don’t have. Instead of immediately suggesting what you would do, coaching empowers your team members to solve their own challenges.

How to apply this tool: Ask clarifying questions that help make the options more concrete, such as “What options do you have to make progress toward that outcome?” or “What other options do you have?” or “What do you want to try first?”

For example, say your direct report is relying on the Creative team to fulfill a key dependency before they can move forward with a campaign. The designer they work with hasn’t shared any updates, and your team member is worried about the project status. You could ask: “What options do you have?” and have your direct report come up with their own ideas before you share any feedback.

Coaching Tool #3: Acknowledging Strengths

When to use it: A team member has imposter syndrome or doesn’t feel confident in their ability to tackle a challenge.

If you took the fix-it approach, you might default to saying:

- “Don’t worry, you got this!”

- “I know you can do it!”

- “Have more confidence in yourself!”

Here’s why you should use coaching instead: Cheerleading often intensifies imposter syndrome because it widens the gap between lofty expectations and where the person sees their own capabilities. In coaching, we increase someone’s confidence by bringing awareness to their specific gifts — this helps them understand how they can apply their skills and strengths to the situation at hand.

How to apply this tool:

- Remind them of strengths they’ve demonstrated in the past. Ask how they could apply them here. For example: "I hear that you're daunted by the tight timeline for this project. I also know that one of your strengths is designing under constraints. Earlier this year, you found a creative solution that allowed us to deliver the user impact without a major engineering rewrite. What would it look like to fully apply that strength in this situation?"

- Go beyond cheerleading. Instead of lobbing over a “Great job!” after a team member nails a sales call, see if you can name the deeper strength they demonstrated. For example: “Nice job on that call! I noticed that you built strong rapport with the client, made them feel heard, and diffused their concerns about the product. Creating genuine trust with the client is a strength that makes you highly effective.”

Pro-tip to keep in mind: To identify your team members’ strengths, ask them to take the VIA character strengths survey (or another strengths assessment) and share their top five strengths.

Coaching Tool #4: Uncovering Limiting Beliefs

When to use it: A team member has unconscious assumptions that might be holding themselves or someone on their team back. To spot when someone is stuck in a limiting belief, notice that they might say things like “I can’t” or “I’ll never be able to” or other phrasing that feels negative and fixed.

If you took the fix-it approach, you might default to saying: “That’s not true,” or “Don’t think that way about yourself.”

Here’s why you should use coaching instead: Limiting beliefs are often deeply ingrained. Simply denying them doesn't help the other person change. Instead, you can coach them to make their unconscious assumption conscious and shift to a more productive belief.

How to apply this tool:

Start by naming:

- Step 1: When you notice that a direct report has a limiting belief, ask them: “What’s the underlying assumption behind that?” Help them name it and write it down. For example: “I’m too timid to be a leader.”

- Step 2: Help them separate observations from interpretations. Observations are things we see or how we feel in our body. Interpretations are the meaning that we layer on top of these observations. We can separate them and notice how our interpretations don't necessarily follow what we're observing in the real world. For example: Your direct report says that they get nervous when they have to speak up in meetings and when they finally do, they speak softly and use a lot of filler words. This causes their team members to not take their ideas seriously. They interpret this to mean that they won’t be a great leader.

Then shift into reframing:

- Step 3: Brainstorm alternative narratives that are more positive and helpful. One way to do this is to shift from negative language to positive language. For example: Your direct report reframes the original narrative from “I’m too timid to be a leader” to “I want to practice my public speaking skills, so I feel l more prepared and comfortable speaking up in meetings.”

- Step 4: Finally, you can help your direct report test these alternatives — for example, helping them find a speaking coach and giving them an opportunity to present at the next Business Review meeting.

COACHING IN PRACTICE:

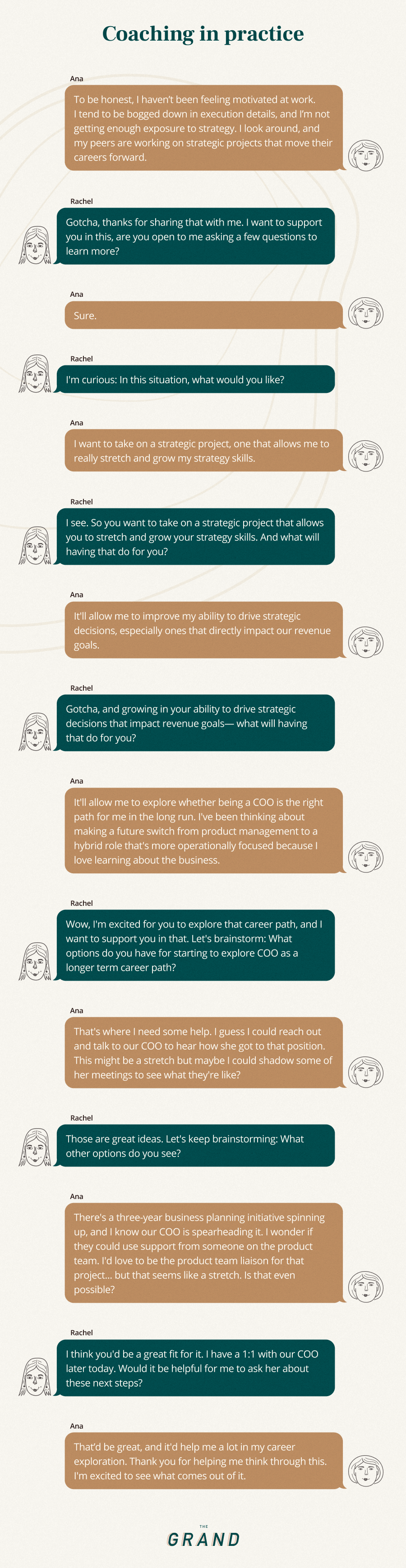

Referring back to our earlier example of the pitfalls of fixing — what might happen if the manager (Rachel) used a coaching approach instead?

In this alternate scenario, instead of assuming that their direct report is after a promotion, the manager digs deeper. She uncovers that her team member is interested in exploring a career pivot — an insight that she wouldn’t have known without asking open and honest questions. Armed with knowledge about what her direct report is solving for, the manager can be a much more effective ally and advocate.

When not to use coaching:

But a manager who only coaches won't be very effective. Other skills, such as delegation, goal setting, and making decisions, are also important.

Coaching skills are tools — not the whole toolbox.

Imagine that a direct report wants to understand the organization's strategy and KPIs so they know how their work contributes to the bigger picture. In this situation (unless the report is a senior contributor to the strategy), it would be frustrating for the manager to start with coaching and turn the question back on their team member. The team member might think: "You're asking me what the strategy is?" and wonder if the company's leadership lacks direction.

It'd be helpful for the manager to first provide clarity about the strategy and metrics that matter, then follow up with open ended questions to get feedback from their direct report: "How are you thinking about your team's goals in relation to the strategy?" Or "From your vantage point, what might be the biggest blind spots in our stated strategy?"

Additionally, coaching is not the right approach when you:

- Are dealing with an urgent, high stakes problem: If getting something right is crucial and urgent, and the responsibility is a stretch for your team member, coaching isn’t appropriate. You'll need to jump in and provide swift direction. Your team members can still learn by shadowing your instruction and observing how you handle the urgent situation.

- Need to give feedback: Coaching isn’t a replacement for clear, actionable feedback, but it can amplify the effectiveness of your feedback. If you’ve noticed an opportunity for your team member to improve, share the feedback directly. Then add an open and honest question to deepen their understanding of the feedback or brainstorm next steps. For example: “I’ve noticed that in executive meetings, you defer to others to answer questions about your domain. I’d love for you to own those questions and demonstrate your expertise. What do you think that would take? How can I support you in doing that?”

- Are training a less experienced team member: Coaching is most effective when your team member already has foundational competence in a task. If your team member does not have the basic skills for their role — maybe they're new or taking on a project outside their realm of experience — start with instruction and mentorship. For example, if your team member is presenting to the executive team for the very first time, it’s appropriate to share advice about how to frame their points and structure their slides. You can drop in open questions to help them reflect on their learning: "How are you taking in this new skill? What has resonated for you? What's been challenging, and where do you want to dig in deeper?" Once they grasp the basics, you can spend more time coaching to help them grow.

- Are managing someone who’s struggling to perform: A direct report who isn’t meeting baseline expectations for their role needs clear expectations about what it takes to get to good performance standing. Empathy is important, but asking too many open-ended questions won’t set them up for success. Use a more directive approach in these situations.

Getting started with coaching:

It can feel daunting to master all of these new coaching skills overnight. As you look to incorporate new techniques into your day-to-day approach, keep these tips in mind:

Start small

Start small and think about one step you can take to incorporate coaching into your management approach. It can be as simple as asking a few open and honest questions during your 1:1s this week. Then, in the next two weeks, start introducing the outcome shift and other tools we covered above.

Express your intention

It can be jarring for your team members if you drastically change your management approach. Set context for this shift. Let them know you’ll be trying a different approach by introducing more coaching practices into your work together.

Get feedback and adapt your approach

Create a timeline with specific check-ins where you explicitly talk about what’s working well and what they’d like to see more of. Set up time on your calendars to have this feedback conversation so you can both learn from it and adapt accordingly.

Be patient with yourself

You’re not always going to get it right. Often, you’ll ask a question that doesn’t land, or run through an options exploration session that doesn’t actually get to a viable solution. That’s okay. Be patient and keep trying. Good management is a practice, one that we should hone every single day.

In our experience working with hundreds of managers, we’ve found that the ones who are intentional about getting incrementally better each day are the ones who make the biggest impact on their teams.

Management isn’t about having the expertise or know-how off the bat, but rather, understanding the needs of your team and adapting your style to best support them.

Cover photo by Getty Images / tomertu. Graphics courtesy of The Grand.